3) Options for next steps on building names

This is page 5 of a 7 page report. View the report contents or download the full Consultation and Engagement Report (PDF, 2,289kB).

3.1 This section of the report considers the options for removing or retaining the names of the University’s buildings and describes the process by which a determination can be made.

3.2 The report refers to ‘denaming’, which describes the process of removing an existing name from a building and separates it from the process of determining a new name. For simplicity, the usual term used is ‘renaming’, but this term implicitly recognises the two separate acts of denaming and naming. In practical terms, denamed buildings may assume a simple address derived from the street name. In some cases (e.g. University buildings on Tyndall Avenue or Colston Street), this may not be desirable and it may be determined that buildings require renaming also.

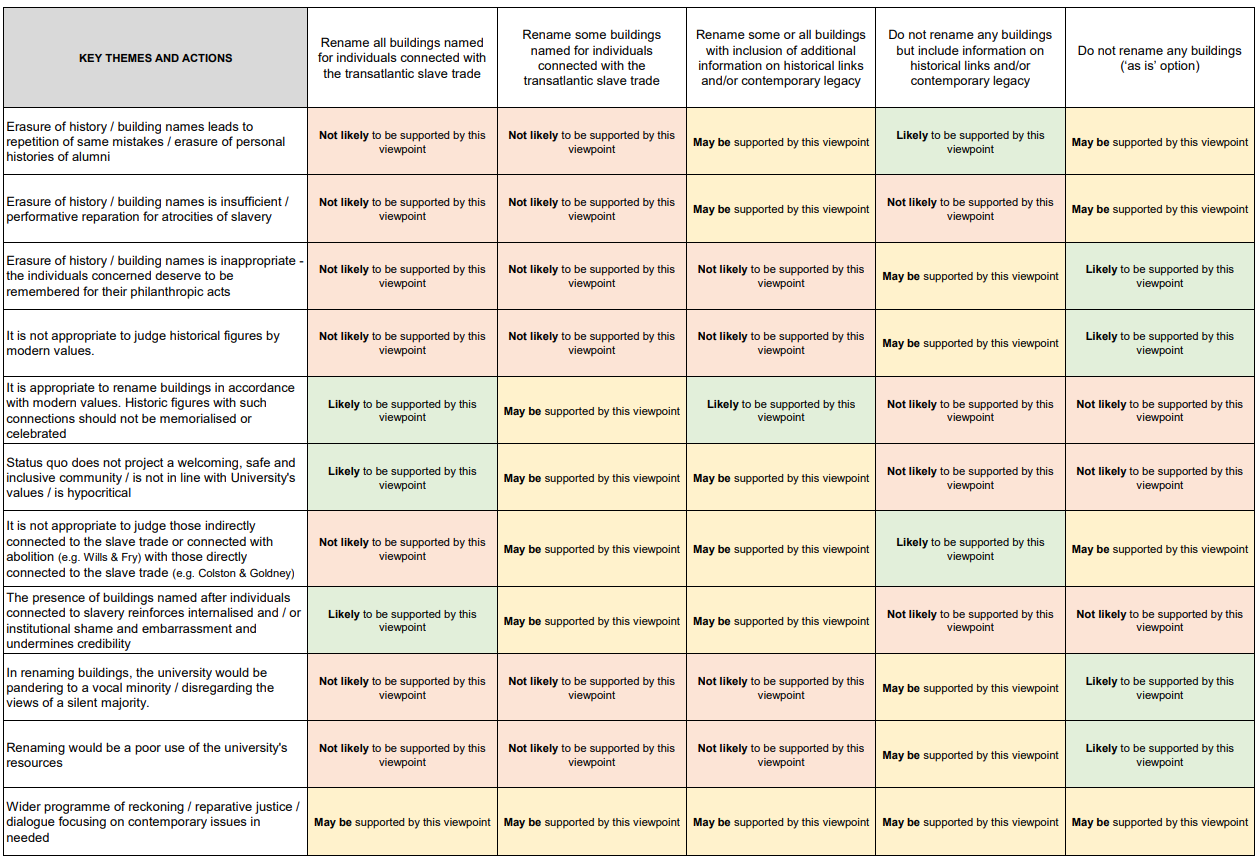

The five options considered are:

- Dename and/or rename all buildings named for individuals connected with the Transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans.

- Dename and/or rename some buildings named for individuals connected with the Transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans, employing a ‘case-by-case’ or principles-led process used to determine which buildings are to be de/renamed.

- Dename and/or rename some or all buildings with inclusion of additional information on historical links and/or contemporary legacy.

- Do not dename or rename any buildings but include information on historical links and/or contemporary legacies.

- Do not dename or rename any buildings (‘as is’ option). These options are placed into a matrix format in fig 6.

The options have been considered against each of the main points of view that the qualitative analysis identified in the survey and an assessment is made on the degree to which each of these points of view would be aligned to a general position on renaming buildings.

View image full size (opens in new tab).

View image as text.

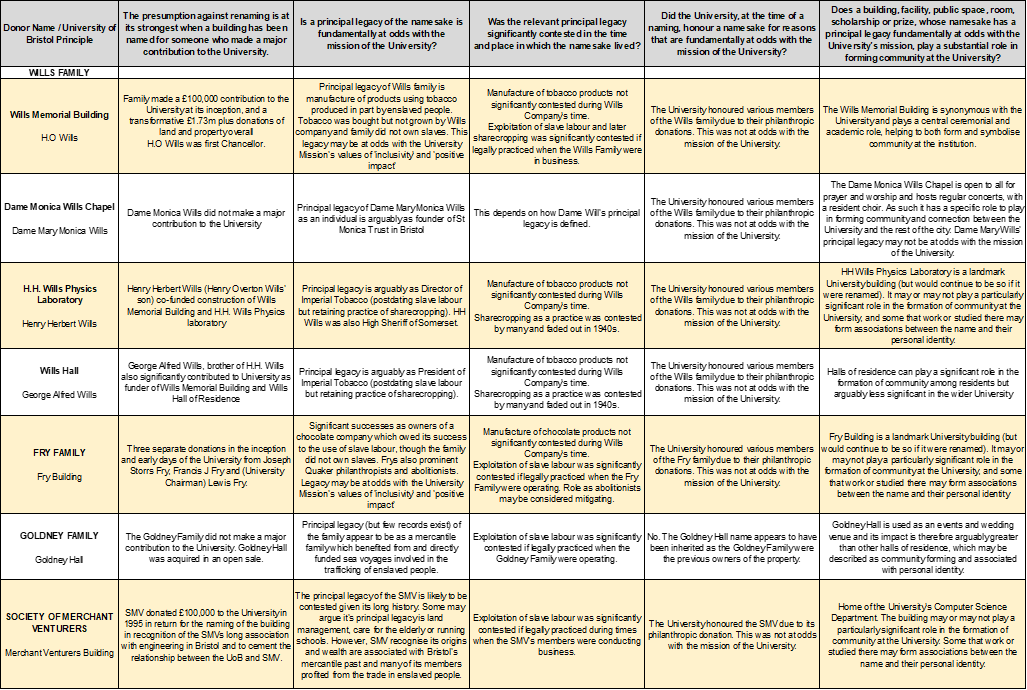

3.3 Applying University of Bristol Renaming Principles

The matrix in Fig. 7 considers the individuals, families and bodies connected to the building names within the scope of the consultation against the University’s principles on Renaming, (see section 1.3). This provides a more detailed understanding of the similarities and differences between each case, and how these relate to the Renaming Principles. Applying the principles provides no definitive conclusions but should help guide decision-making.

There are a few additional points to make about the application of the Renaming Principles. Firstly, there are subjective elements within the principles, including the identification of an individual’s ‘principal legacy’, or the degree to which a building named for them helps in the formation of community within the University. The current responses provided in the Legacies of Slavery report reflect that subjectivity and may be challenged and interrogated.

In addition, the principles seek to systematise the process of determining whether a building name should change and so are not necessarily designed to understand the emotional impact – positive or negative - of the continued presence of particular individuals within the University’s symbols and building names.

The matrix in Fig. 7 does not consider the first principle: that is, a ‘strong presumption against renaming…according to the values of the namesake’, and the weight this principle should be given in overall determination. This is a matter for the University Executive Board. The principles make clear however that renaming should be an 'exceptional event’, particularly where ‘a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.’ There are differences between major donors such as Wills and Fry - families that indisputably made a major contribution to the University - and Goldney in this respect.

The University should determine the relative weight it gives to the consultation process, Renaming Principles and research in its decision-making. All should be considered evidential factors, guiding the decision-making process. However, there are other factors that may require consideration, including:

3.3.1 Financial implications

The practicalities associated with renaming a building are costly. Some responses in the consultation from students, faculty, alumni and the wider community questioned the use of university funds in such an endeavour, where such funds might be used for other programmes they considered more important, such as tackling contemporary inequality of opportunity in the city. Others contend that funds need to be made available for a range of anti-racism and reparative justice measures, from renaming to decolonising the curriculum to community projects.

View image full size (opens in new tab).

Content from the matrix table (figure 7).

The presumption against renaming is at its strongest when a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.

Family made a £100,000 contribution to the University at its inception, and a transformative £1.73m plus donations of land and property overall H.O Wills was first Chancellor.

Is a principal legacy of the namesake fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

Principal legacy of Wills family is manufacture of products using tobacco produced in part by enslaved people. Tobacco was bought but not grown by Wills company and family did not own slaves. This legacy may be at odds with the University Mission's values of 'inclusivity' and 'positive impact'.

Was the relevant principal legacy significantly contested in the time and place in which the namesake lived?

Manufacture of tobacco products not significantly contested during Wills Company's time. Exploitation of slave labour and later sharecropping was significantly contested if legally practiced when the Wills Family were in business.

Did the University, at the time of a naming, honour a namesake for reasons that are fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

The University honoured various members of the Wills family due to their philanthropic donations. This was not at odds with the mission of the University.

Does a building, facility, public space, room, scholarship or prize, whose namesake has a principal legacy fundamentally at odds with the University’s mission, play a substantial role in forming community at the University?

The Wills Memorial Building is synonymous with the University and plays a central ceremonial and academic role, helping to both form and symbolise community at the institution.

The presumption against renaming is at its strongest when a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.

Dame Monica Wills did not make a major contribution to the University

Is a principal legacy of the namesake fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

Principal legacy of Dame Mary Monica Wills as an individual is arguably as founder of St Monica Trust in Bristol

Was the relevant principal legacy significantly contested in the time and place in which the namesake lived?

This depends on how Dame Will's principal legacy is defined.

Did the University, at the time of a naming, honour a namesake for reasons that are fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

The University honoured various members of the Wills family due to their philanthropic donations. This was not at odds with the mission of the University.

Does a building, facility, public space, room, scholarship or prize, whose namesake has a principal legacy fundamentally at odds with the University’s mission, play a substantial role in forming community at the University?

The Dame Monica Wills Chapel is open to all for prayer and worship and hosts regular concerts, with a resident choir. As such it has a specific role to play in forming community and connection between the University and the rest of the city. Dame Mary Wills' principal legacy may not be at odds with the mission of the University.

The presumption against renaming is at its strongest when a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.

Henry Herbert Wills (Henry Overton Wills' son) co-funded construction of Wills Memorial Building and H.H. Wills Physics laboratory

Is a principal legacy of the namesake fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

Principal legacy is arguably as Director of Imperial Tobacco (postdating slave labour but retaining practice of sharecropping). HH Wills was also High Sheriff of Somerset.

Was the relevant principal legacy significantly contested in the time and place in which the namesake lived?

Manufacture of tobacco products not significantly contested during Wills Company's time. Sharecropping as a practice was contested by many and faded out in 1940s.

Did the University, at the time of a naming, honour a namesake for reasons that are fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

The University honoured various members of the Wills family due to their philanthropic donations. This was not at odds with the mission of the University.

Does a building, facility, public space, room, scholarship or prize, whose namesake has a principal legacy fundamentally at odds with the University’s mission, play a substantial role in forming community at the University?

HH Wills Physics Laboratory is a landmark University building (but would continue to be so if it were renamed). It may or may not play a particularly significant role in the formation of community at the University, and some that work or studied there may form associations between the name and their personal identity.

The presumption against renaming is at its strongest when a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.

George Alfred Wills, brother of H.H. Wills also significantly contributed to University as funder of Wills Memorial Building and Wills Hall of Residence

Is a principal legacy of the namesake fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

Principal legacy is arguably as President of Imperial Tobacco (postdating slave labour but retaining practice of sharecropping).

Was the relevant principal legacy significantly contested in the time and place in which the namesake lived?

Manufacture of tobacco products not significantly contested during Wills Company's time. Sharecropping as a practice was contested by many and faded out in 1940s.

Did the University, at the time of a naming, honour a namesake for reasons that are fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

The University honoured various members of the Wills family due to their philanthropic donations. This was not at odds with the mission of the University.

Does a building, facility, public space, room, scholarship or prize, whose namesake has a principal legacy fundamentally at odds with the University’s mission, play a substantial role in forming community at the University?

Halls of residence can play a significant role in the formation of community among residents but arguably less significant in the wider University

The presumption against renaming is at its strongest when a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.

Three separate donations in the inception and early days of the University from Joseph Storrs Fry, Francis J Fry and (University Chairman) Lewis Fry.

Is a principal legacy of the namesake fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

Significant successes as owners of a chocolate company which owed its success to the use of slave labour, though the family did not own slaves. Frys also prominent Quaker philanthropists and abolitionists. Legacy may be at odds with the University Mission's values of 'inclusivity' and 'positive impact'

Was the relevant principal legacy significantly contested in the time and place in which the namesake lived?

Manufacture of chocolate products not significantly contested during Wills Company's time. Exploitation of slave labour was significantly contested if legally practiced when the Fry Family were operating. Role as abolitionists may be considered mitigating.

Did the University, at the time of a naming, honour a namesake for reasons that are fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

The University honoured various members of the Fry family due to their philanthropic donations. This was not at odds with the mission of the University.

Does a building, facility, public space, room, scholarship or prize, whose namesake has a principal legacy fundamentally at odds with the University’s mission, play a substantial role in forming community at the University?

Fry Building is a landmark University building (but would continue to be so if it were renamed). It may or may not play a particularly significant role in the formation of community at the University, and some that work or studied there may form associations between the name and their personal identity

The presumption against renaming is at its strongest when a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.

The Goldney Family did not make a major contribution to the University. Goldney Hall was acquired in an open sale.

Is a principal legacy of the namesake fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

Principal legacy (but few records exist) of the family appear to be as a mercantile family which benefited from and directly funded sea voyages involved in the trafficking of enslaved people.

Was the relevant principal legacy significantly contested in the time and place in which the namesake lived?

Exploitation of slave labour was significantly contested if legally practiced when the Goldney Family were operating.

Did the University, at the time of a naming, honour a namesake for reasons that are fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

No. The Goldney Hall name appears to have been inherited as the Goldney Family were the previous owners of the property.

Does a building, facility, public space, room, scholarship or prize, whose namesake has a principal legacy fundamentally at odds with the University’s mission, play a substantial role in forming community at the University?

Goldney Hall is used as an events and wedding venue and its impact is therefore arguably greater than other halls of residence, which may be described as community forming and associated with personal identity.

The presumption against renaming is at its strongest when a building has been named for someone who made a major contribution to the University.

SMV donated £100,000 to the University in 1995 in return for the naming of the building in recognition of the SMVs long association with engineering in Bristol and to cement the relationship between the UoB and SMV.

Is a principal legacy of the namesake fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

The principal legacy of the SMV is likely to be contested given its long history. Some may argue it's principal legacy is land management, care for the elderly or running schools. However, SMV recognise its origins and wealth are associated with Bristol's mercantile past and many of its members profited from the trade in enslaved people.

Was the relevant principal legacy significantly contested in the time and place in which the namesake lived?

Exploitation of slave labour was significantly contested if legally practiced during times when the SMV's members were conducting business.

Did the University, at the time of a naming, honour a namesake for reasons that are fundamentally at odds with the mission of the University?

The University honoured the SMV due to its philanthropic donation. This was not at odds with the mission of the University.

Does a building, facility, public space, room, scholarship or prize, whose namesake has a principal legacy fundamentally at odds with the University’s mission, play a substantial role in forming community at the University?

Home of the University's Computer Science Department. The building may or may not play a particularly significant role in the formation of community at the University. Some that work or studied there may form associations between the name and their personal identity.

3.3.2 Opportunity cost

Where younger generations and current members of the University are more likely to show support for renaming, older people, including Alumni are less likely. Comments received from Alumni suggest that Alumni donations to the University may be negatively impacted by renaming. An alternative view is that a building renaming process may be an opportunity to attract a significant donation.

3.3.3 Existing relationships

The University operates in a broader city-wide context, and as a Civic University is committed to ensuring its operation contributes positively to life in the city in general. In reality this means that the institution maintains a networks of partnerships in the community, as education provider, research body, funder, as a beneficiary of funds, as a landlord, developer, and project delivery agency across the city. The decision on building renaming should be considered in light of the positive and negative impact on this network of partnerships and relationships in the broader community.

3.3.4 Future relationships

The University may wish to consider whether prospective students, and particularly those from Black communities, may be deterred from attending the University if they perceive the response to this exercise has been mishandled in any way, or indeed whether the University projects a sufficiently safe and welcoming environment in its maintenance of existing symbols and building names.

3.3.5 Pre-existing legal agreements, naming rights etc

The University has consulted its legal team and has established that there are no extant legal restrictions preventing it from renaming any building.