How do young refugees and their families encounter England’s education system?

The fourth goal of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDG 4) aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education” and opportunities for all (UN, 2016). Accordingly, young refugees in England are entitled to education and required to attend school in England. However, there is limited information about the young refugees in England’s schools. Responsibility for refugees’ education sits with local authorities meaning there is limited information about the young refugees in England’s schools nationally.

About the research

The lived experiences of young people in contexts of migration, for example interrupted education, being bilingual or multilingual, having no previous experience of ‘formal’ schooling, requires the education system to have school-wide strategies to support their learning. This research looked at how young refugees and their families encountered England’s education system, their perspectives of education in England and how schools engaged with young refugees’ knowledge, practices and skills.

This study aimed to provide clearer understanding of how policy meets refugee families’ lived experiences, including how they may be excluded from it at the intersection of education, integration and asylum policies. Children’s and adolescents’ perspectives and aspirations are rarely at the centre of policy development and implementation.

Key findings

The study included three refugee families, one with asylum-seeker status, to investigate the challenges that young refugees and their families face while navigating England’s education systems. Participants were a mix of secondary and primary school ages, all of them attending different schools in the UK and some had experience of changing schools regularly. This study also heard from school staff at a secondary school, particularly the English as an Additional Language specialists (EAL) who worked closely with the refugee young people and their families.

Research findings indicated that the combination of asylum and education policies lead to young people being excluded. Asylum seeker dispersal, national policies that move asylum seekers across the UK, and temporary accommodation may delay young people’s access to education and result in young people facing long commutes to school or having to change schools during the school year. The participants’ education was also impacted by inadequate living conditions, including limited access to technology and the internet, making it hard to complete schoolwork at home.

Refugee families also face difficulties such as language barriers, (in education but also in other contexts such as access to healthcare), using public transport, and opening bank accounts.

After the first school, then I had to leave and change to another school for basically 2 years. But I started, like halfway through. That was really difficult to start during the middle of the year in a new school…

They (a young man and his father) were living in one room with a single bed and no heating. The father slept on the floor and let his son sleep on the bed. They didn’t have bedding or enough clothes.

Schooling

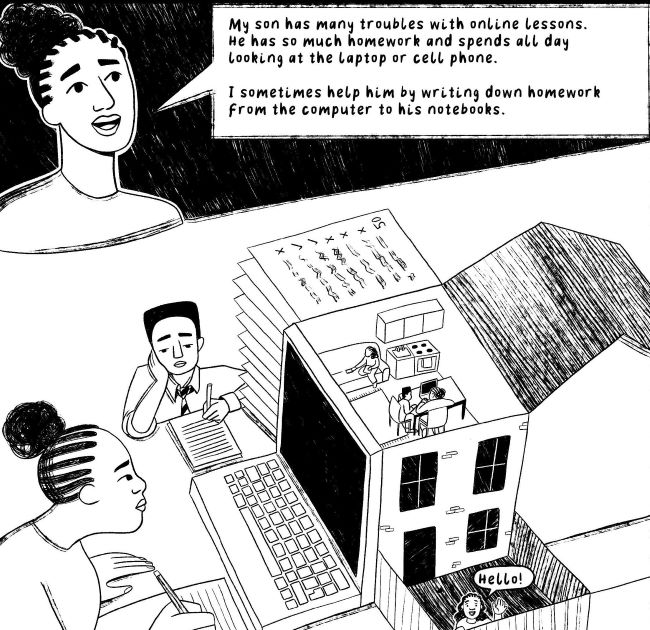

Language barriers, starting school mid-year and limited assistance from the education system create barriers for newly-arrived children to access the curriculum. Learners took home a significant amount of homework without support to complete them. The study heard from mothers who wanted to participate in their children’s education but felt inadequate to help their children.

The research also found weak relationships between schools and families, likely intensified by COVID-19. This lack of insight into family life made it more challenging to involve parents (Figure 2).

The education system’s monolingual approach creates barriers for newly-arrived children to access the curriculum, especially when schools lack school-wide strategies to facilitate learners’ to access the curriculum content. Young people who start school mid-year face additional challenges to ‘catch up’ with their classmates within a context where they are offered limited assistance from the education system. In this study, the learners took home a significant amount of homework and assignments although they had limited to no support to complete them. The mothers who also participated in this study stated that they wanted to participate in their children’s education but due to language barriers and unfamiliarity with England’s school system made them feel inadequate to help their children. This led to another important finding that showed that schools and families had limited to no partnerships. The pre-existing (dis) connections between schools and families intensified after the COVID-19 outbreak. The teachers appeared to have little insight into young people’s and their families’ experiences making it more challenging to involve parents in their children’s education (Figure 2).

School-wide approaches aimed at supporting these families were lacking. Safeguarding leads acknowledged the extra barriers faced, but often relied on a few EAL specialists to communicate with families. Safeguarding young refugees requires an institutional approach where all staff invest in welcoming and supporting them and families. Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) may particularly require schools to implement specific safeguarding strategies.

School-wide approaches aimed at supporting these families were lacking.

Safeguarding leads acknowledged the extra barriers faced, but often relied on a few EAL specialists to communicate with families. Safeguarding young refugees requires an institutional approach where all staff invest in welcoming and supporting them and families. Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) may particularly require schools to implement specific safeguarding strategies.

The school system’s unpreparedness

Schools and school staff often didn’t have sufficient support or resources to receive young migrant learners new to English. Often responsibility was placed on EAL specialists rather than their involvement in all subjects.

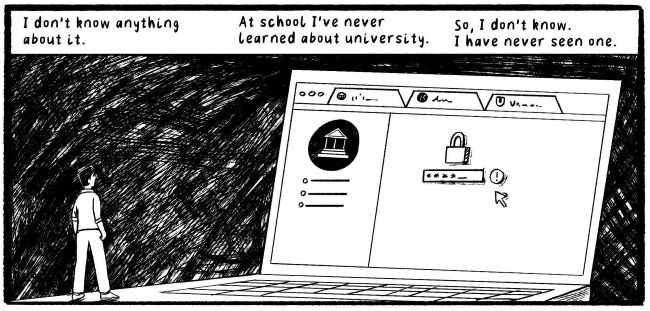

Aspirations and transitions into further education

Families in the study expressed interest in pursuing further education and curiosity about studying at university. Their mothers were invested in their education and supportive of their aspirations. At secondary school, some young participants said they were unsure about how to transition into further and higher education while others stated that they were encouraged to attend a specific college and pursue courses in the construction trades (Figure 3).

Policy implications and Practice recommendations

Visibility in policy: National and local policies accounting for the education young refugees are needed in England. It is essential to highlight that schools and teachers face barriers in providing appropriate provisions. The presence of policies may be helpful in supporting additional funding focusing on the education of young people in contexts of migration arriving in the country.

Funding and training: Schools need additional funding and resources to provide appropriate EAL assessments and EAL education. More funding should be allocated for speech-language therapists, for example. Educators would benefit from more further insights preparing them to teach newly-arrived English language learners.

Language: Young learners new to English should be included in classes in all subjects. Teachers could benefit from EAL training, learning to teach their subjects through an EAL perspective that supports learning language and subject content. Schools should develop school-wide strategies to welcome and build a stable relationship with families.

- Curriculum: Young learners will benefit from curriculum content that reflects their realities, requiring institutional changes in how Britain’s colonial history and violence, and its everlasting consequences of racism(s), poverty and forced displacement, are taught in schools (Figure 4).

Welcoming refugee families: Schools should provide a ‘welcome pack with information in the families’ preferred language. Information could focus on explaining the English school system’s expectations and behaviour policy. Considering that schools may have difficulty accessing information about refugees’ backgrounds, schools can gain insight into families’ and young people’s lived experiences by building partnerships with families and drawing from their expertise, perspectives and aspirations.

- Transitions: Young learners need academic progression pathways designed to support them transition from secondary education to further and higher education. They need clear guidance on what opportunities are available to them and how they can be accessed.

Further information

The illustrations displayed in this report are from the zine, Refugee Stories: Education: Obstacles and Aspirations, created to share this study’s findings visually in and beyond academic settings. The zine was funded by the University of Bristol’s Temple Quarter Engagement Fund.

Main image: Figure 1: Illustration of Olivia based on research findings taken from Refugee stories: Education: Obstacles and aspirations, edited by Câmara (2023), illustrated by Arc Studio and funded by the University of Bristol’s Temple Quarter Engagement Fund.

Câmara, J. N. (2024). Funds of knowledge: Towards an asset-based approach to refugee education and family engagement in England. British Educational Research Journal, 50, 876–904. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3946

Câmara, J. N. (Ed.). (2023). Refugee stories: Education: Obstacles and aspirations. Illustrations by Arc Studio

Câmara, J. N. (2020). “The government gives me £35 a week to buy food… During the

lockdown, my kids do not receive free school meals.” openDemocracy

United Nations. (2016). Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development.

Author

Dr Jáfia Naftali Câmara, Honorary Research Associate and Foundation Programme Individual Project Supervisor, University of Bristol, British Academy Research Fellow, Centre for Lebanese Studies and University of Cambridge