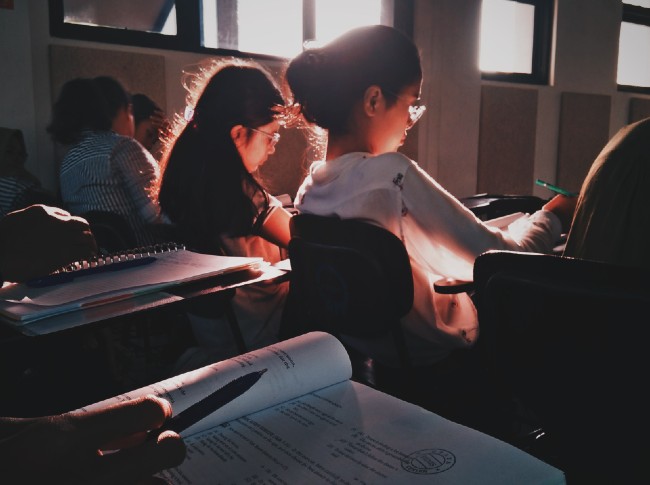

What happens when migrant pupils turn 16?: A scoping study of 16+ provision for young migrants in the UK

We investigated what happens when young people reach the end of compulsory schooling at age 16 and don’t have the English proficiency skills to continue further study. Many go to college to continue their education but find themselves taking English classes as long as they have funding to do so (this typically runs out after three years).

We knew from previous research that teachers, schools and colleges work exceptionally hard to help young migrants continue in education. We wanted to know what they do already, what they think would be more effective, and what practical and policy challenges need to be resolved to make that possible.

We found dedicated and talented teachers trying to support learners with complex and often poorly understood needs, in a highly fragmented education system. There is a significant funding gap for these learners, who fall between the school-based and adult education budgets. There is also little coordination between professionals serving different needs (from mental health specialists to immigration solicitors to housing officials) and widespread assumptions about language and subject learning that limited students’ opportunities to continue in education.

This briefing highlights a number of promising opportunities to overcome those barriers.

Policy recommendations

1. College programmes are best for innovative work.

Colleges are able to create innovative programmes of study with fewer constraints than schools. They have the organisational capacity to offer high-quality teaching and assessment. e.g. ‘early college’ programmes for learners aged 14-16, or specialist provision for learners aged 16+.

2. Specialist training for both teachers and leaders is needed.

Colleges are not always well equipped to support recently arrived migrant learners, who may have complex needs or insecure housing and legal status. Specialist training is needed for both teachers and leaders but does not exist at present.

3. A regional approach, bringing together different professions as well as student and community groups, is essential.

There is a lack of coordination between professionals, charities, community groups and others that serve each learner. A regional approach (which might focus on a city or county but is not limited to those boundaries) allows direct, personal contact that builds trust and encourages innovation.

4. Funding is challenging but not insurmountable.

Funders recognise the challenges and are keen to support innovative programmes but found this message did not always reach colleges.

5. Scalable models should be prioritised.

We found several examples of excellent practice but they rely on the experience and structures of individual institutions. Identifying scalable models would allow more learners to benefit.

Key Findings

Our initial research found significant structural barriers but also some promising opportunities to overcome them:

1. Limiting assumptions about language and learning

We found widespread assumptions that students must reach a high level of English proficiency before they could join academic or vocational (‘subject’) classes. Learners are therefore unable to progress in their learning. This is not supported by the research evidence, which points to combined (language and subject) courses as more promising.

2. Funding

There is a funding gap for 16-18 year old learners studying English language programmes at college. Further, some funding is limited to three years, which the evidence shows is not enough time to develop adequate proficiency in English. Combined (language and subject) courses are a promising way to resolve this, but may be more challenging to organise, staff and fund. We found some flexibility in funding which may allow new programmes to be developed, but this was not always apparent to the colleges involved.

3. Complex needs are not fully understood by providers

Learners who reach 16 with limited English are often those with complex needs and complex lives. These are not well understood in colleges, in part because they relate to experiences outside education (such as insecure housing and legal status, or mental health, or isolation). This means that enrichment and pastoral elements are particularly worthwhile, and that programming for such learners would benefit from input from non-education professionals.

4. Disconnect between schools, colleges and wider services

We focused on young people as they move from school to college, but found no systematic coordination between them. We also found that young people were involved with a range of professional services outside education but that there was little day-to-day coordination with the school or college. This resulted in significant gaps in provision and adverse outcomes.

5. Lack of scalable programmes

We found some excellent examples of innovative programmes but they are generally small-scale and difficult to replicate in the current environment.

Further information

Further funding was awarded by PolicyBristol from the Research England QR Policy Support Fund (QR PSF) 2022-24 to develop the Bristol Plan for Migrant Learners

Authors

Dr Robert Sharples, School of Education, University of Bristol (Principal Investigator), Jules Godfrey, School of Education, University of Bristol, Syd Ahmed, School of Education, University of Bristol