Rethinking the governance of external consultancy in the public sector

Management consultancy use in the public sector has long provoked controversy, with questions over efficiency, effectiveness and ethics. These continue to be raised globally, with occasional scandals with firms such as McKinsey in the USA, PwC in Australia or Bain & Co. in the UK. This all suggests that approaches to managing the use of consultancy have not been effective. In fact, there are few checks and balances on consultancy which is surprising given how much is spent on it (over £3 billion in the UK public sector in 2023-4). One periodic policy response, currently planned by the UK government, is to cut the use of external consultants and do more work internally through an empowered and enlarged civil service. This ‘insourcing’ mostly makes sense, but there will always be some need for external expertise. So, what can be done by both clients and consultancies to help make it effective?

About the research

Our research reviewed different ways to strengthen the governance of external consultancy. We focused on what is different and what can be learned from developments or challenges elsewhere. In particular, our proposals build on emerging trends in some private sector organisations around greater transparency and more ‘socially responsible’ practices and values as well as returning to some classic issues around expert advice such as the role of incentives and of other outsiders to keep an eye on things.

Policy implications

- Traditional forms of governance need to be strengthened or radicalised to be effective (e.g. make permanent National Audit Office monitoring of consultancy spend; procurement rules to limit repeat business and; independent licensing of consultants).

- Reform pay and promotion systems to discourage ‘over-selling’ by consultancies and conservativeness among both clients and consultants so each party can challenge the other more easily - speak ‘truth to power’.

- Open consulting - use social/open-access media and regulation to share evaluations of projects/firms (‘ratemyconsultancy.com’); provide declarations of conflicts of interests and; share outputs/knowledge.

- Strengthen role and range of third-party scrutiny of consultants and clients, using increased transparency from open consulting (e.g. ‘meta’ consultants; public service users as activists; journalists; NGOs; trade unions).

- Leverage genuine, not superficial, moves towards socially responsible governance (e.g. ‘BCorps’) and values in consulting and generate client demand for such approaches.

In short:

- Consultancies need to reform pay/promotion away from revenue and towards social responsibility and openness.

- Clients must also be more open, to change and scrutiny, and focus on knowledge transfer and sharing.

- Policy makers and regulators should not rely on self-governance, but strengthen existing approaches and support openness and external scrutiny.

Key findings

From our review, we found that some core characteristics of consultancy mean that established forms of governance (e.g. procurement rules and professionalisation of consultants) are by-passed, resisted and/or ineffective. For example, consultancy is usually co-produced and hard to evaluate precisely; clients are often conservative/secretive; and consultants are mostly rewarded to sell regardless of what is needed or right.

These are familiar issues, meaning that, not only does current governance need to be strengthened, but new approaches are required. In particular, little has been done to address incentives in consultancy. While staff may often be paid and promoted on diverse ‘balanced’ criteria, in practice selling is ‘sovereign’. This means that clients (indirectly, the public) are often exploited or, at best, not challenged. Further, clients often do not want to be challenged or placed under scrutiny. Both parties then, share an interest in secrecy under the guise of ‘commercial confidentiality’.

More optimistically, some current developments suggest improvement is possible. For instance, there are moves in the private sector, including consulting and its Gen Z recruits, to adopt values beyond simply profit, towards diverse stakeholders and greater transparency. These echo some traditional professional values and can be leveraged to develop new types of firms and consultants who can be progressive, if clients allow.

Where such moves are absent or adopted for image only, external scrutiny and scandal has helped keep the pressure on reform. This too can be enhanced by the use of technology to help make the market more transparent and allow for ease of sharing knowledge. Indeed, changes in rewards, values, structures and openness cannot guarantee effective governance. Third-party scrutiny will always have an important role to play.

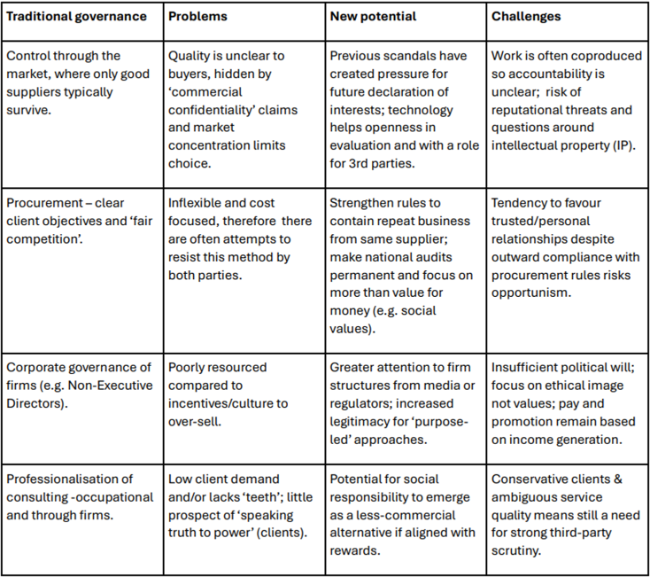

Traditional governance is not working. Our research identifies new opportunities, as well as some ongoing challenges which we’ve outlined in the table below.

Further information

Full article available: Governing public sector use of external management consultancy—beyond client procurement and consultant professionalization (tandfonline.com)

Related research:

What is the cost of NHS consultancy? (youtube.com).

Managing change without the use of external consultants, how to organise consultant managers.

Management consultancy and inefficiency in the NHS: time for an urgent review.