When people hear the word autism, they often think of Sheldon Cooper/Rain Man type characters. I don’t relate to either of them. First off, I’m a female. But also I’m not super smart, I don’t have an amazing memory, and I’m not ‘obviously’ autistic. I can make eye contact, I’m great at sarcasm, and for the most part I’m really good at acting like I fit in, but these things don’t always come naturally to me.

In this piece, I’m going to share some of my experiences, and things I have found both helpful and unhelpful. I want to emphasize, however, that these are my own experiences and reflections. No two people, autistic or otherwise, are the same. My hope is that by sharing this, I may help others to understand autism, and help other autistic students feel less alone, but please keep in mind that I do not speak for every autistic person.

The National Autistic Society defines autism as being “a lifelong, developmental disability that affects how a person communicates with and relates to other people, and how they experience the world around them.” 1

2.4% of the UK student population are diagnosed with autism, and less than 40% of these people complete their university education2 – meaning that they are 10 times more likely to drop out (60% vs 6.3% overall dropout rate3). To put this into context, the student population of Bristol University was 20,304 for the 2019/20 year4. That means 487 students have an autism diagnosis, but only 195 of us will complete our degree courses. That’s not many.

I am determined to be one of the 195. I’ve been incredibly lucky with the support I’ve received from staff at Bristol, but 1.08% of all university graduates being autistic is not good enough.

Autism, masking and fitting in

Autism is significantly under-diagnosed in females, with males being four times more likely to receive the diagnosis5. The reasons for this are complicated, but in part females are less likely to be diagnosed due to ‘camouflaging’ or ‘masking’. These terms refer to the ways in which autistic individuals – particularly females5 - act like their neurotypical peers6. Their autism may therefore not picked up by professionals, family and friends. This underdiagnosis in women can lead to negative consequences such as higher rates of mental illness, possibly as a result of not receiving appropriate support7 , and can increase the difficulties faced by women on the spectrum.

I know a lot about masking. It protected me, but was also likely the reason my autism wasn’t identified for so many years (I received my official diagnosis at the age of 19). Masking has helped me to make friends, fly under the radar, and avoid the negative attention you often get for being different. This poses its own difficulties though; I’m not noticed for being different in a bad way, but I’m not noticed for good reasons either. Hiding is a protection, but it also means the good parts of me aren’t seen. I remain completely average, which can feel difficult sometimes. And so, recently, I’ve been trying to take off my mask and show the true ‘me’. Masking is not only exhausting and demoralising, but it means that the world doesn’t get to see all the great things I, and my autism, have to offer.

How does autism affect me at university?

One of the biggest ways in which my autism affects me is my anxiety levels. If the average person has a baseline anxiety level of 1-2 on a 10-point scale, my baseline is generally a 6. That means that if something happens to increase my anxiety levels, instead of going up to a 3-4 like most people would, my anxiety level is already an 8. Because of this, I have a lot of panic attacks. This is especially obvious when it comes to exams; the anxiety of exams becomes so much for me that I would never be able to reach my full potential.

Another difficulty that having autism poses is how I adjust to change. After years of learning to cope, I can deal with change a lot better now than I could in the past, but things still catch me off guard sometimes. Moving house every year, new lecturers every term, and so many other parts of ‘normal’ uni life can pose a difficulty for people with autism. I have to actively spend time preparing myself before a change, and adjusting afterwards. Some of the situations I find most difficult are ones where I don’t have time to prepare. For example, when one of my lectures changed location midway through term. As soon as that happened – despite attending consistently to that point - I stopped going to the lecture. I didn’t know why, but I felt completely unable to attend; it was like I had a mental block. My brain couldn’t adjust to having the same unit but in a different place without any warning. Reflecting on this has helped me recognise it, and helps stop it happening in the future. However, it would be useful for universities to understand the potential unintended consequences of what must seem like ‘small’ changes to most people.

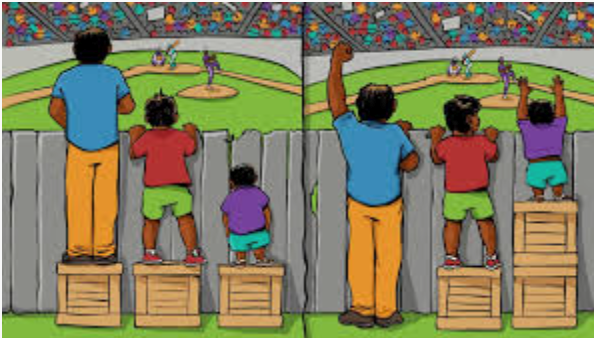

I’m a very logical and literal person, which means that what makes sense to some people doesn’t always make sense to me (and vice versa!). Someone once said that having autism is asking why there is a needle in the haystack. While I see what others often miss, I can also miss what others see. This can prove particularly difficult when assessments are being explained. I sometimes have questions about things that other people take for granted, and on the few occasions staff have not answered questions I have, my learning can be negatively affected. There have been a minority of lecturers who have refused to give any extra explanations to individual students, and expect everyone to use the same information. While I understand their reasoning that everyone should receive the same information and resources, this can prove a barrier to autistic people (and I’m sure the same goes for other neurodiversities that I don’t have experience with). The image below explains this perfectly.8

IMAGE CREDIT: ANGUS MAGUIRE // INTERACTION INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL CHANGE

What has helped?

The most important piece of practical help I have received at uni is around exams. The work of the university disability services, and the support of my school means that I can now be assessed through coursework rather than exams. I find coursework much less anxiety provoking, and it allows me to achieve in ways exams never could. This has made more of a difference than I can explain, and allows me to demonstrate my knowledge in a much more accurate way.

Another thing that has helped has been to have content broken down into smaller sections. This is particularly valuable when I am feeling overwhelmed. My personal tutor, wellbeing advisor, and a couple of other lecturers have really helped me in this regard. Taking the time to sit with me and help me untangle everything has been invaluable, and I am incredibly grateful to the staff members who give their time to help me when I need it.

On the topic of staff, knowing there are people I can go to when I’m having a panic attack or feeling overwhelmed, and who can help me calm down, has been incredibly helpful. The staff in my department have been amazing, not only with helping me in the moment, but also in helping me learn to manage my anxieties. Regular contact with my personal tutor has made a world of difference, as has having ‘safe’ people. If you can be the safe person for someone on the spectrum, I guarantee you will make more of a difference than you could ever understand. As a result of the amazing staff members I’ve come into contact with, I’ve learnt to be a lot better at reaching out when I need help, and that it’s okay to express my needs. There have been some great people at university who have helped me learn to recognize and express when I need extra help, and that is a skill I will take with me through my whole life.

Finally, having advance notice about anything out of the ordinary is incredibly helpful. By allowing me the extra time to process things before they happen, I am able to cope with them a lot better. This can range from things such as having a different lecturer, a different location, or what the content of the lecture will be. Referring to the previous example of when a lecture changed venue, this may have been easier if it had been emailed to us the week before, or if someone checked in with me beforehand to acknowledge the change, as this would help break down the mental block.

Having lectures available 24 hours before the live session is also helpful as I can have a chance to look through and process it so I’m more able to take it in during the lecture. This is available to everyone from most lecturers, but having slides beforehand is very valuable and it would be beneficial if all lecturers ensured this was the case.

What hasn’t helped?

I’m always very cautious who I tell about my diagnosis. I worry about the impact it could have on my future, that people may treat me differently, or that I will be seen in the light of stigma. One of the strangest things I’ve experienced is people sharing their opinions of autism with me once I’ve told them about my diagnosis. I once had someone tell me that they didn’t agree with the premise of diagnosing autism, as it can create a self-fulfilling prophecy and make people act “more autistic.” That isn’t necessarily wrong, as I probably do act “more autistic” since receiving my diagnosis, but that isn’t because of a self-fulfilling prophecy; it’s simply because I actively try not to hide those parts of myself anymore.

Similarly, I was once in a lecture on children with disabilities, and the lecturer set us the task of having a conversation to identify all the potentially difficult things about having a student with autism in the classroom, or of being friends with someone who is autistic. They of course didn’t know that I was on the spectrum - very few people do - but hearing what people were saying was hurtful. The emphasis on all the negatives of autism really outshone the many amazing things about it. I found the courage to speak to the lecturer afterwards and explain why I found it hurtful, but there may be other autistic students who have to listen to these things without being able to express themselves, and that can be incredibly damaging. Please always be mindful of the fact that you don’t know all of your students or peers’ experiences; what you’re saying could be hurting the people around you even if you don’t realise it.

What would I like people to know?

There are lots of great things about being autistic. I’m really passionate about the things that matter to me, I love learning new things, and when I’m allowed to be myself I’m apparently very funny (if people’s reactions to the things I say are to be believed!). But more than anything, I’m a very accepting person. I know what it feels like to be different and to be excluded, so I try my hardest to show people they can be themselves around me.

Autism is my way of being. I don’t know how to experience the world without autism, and so much of my energy goes into navigating a neurotypical world. When I was diagnosed, the psychologist compared being autistic to being left-handed. There isn’t anything inherently wrong with it, but the world just isn’t set out to be accessible to us. I work around it for the most part; I’ve spent 20 years of my life learning to pass as neurotypical, and I’m very good at coping now, but there are still times when it can make things more difficult.

If you are autistic and are coming to university, I want you to know that it is possible. You can be yourself and find your people, you can get the support you need (as long as you let people know) and you CAN be one of the 1.08%. Hopefully one day we can raise that number, but for now if you are one of the 195 at University of Bristol, know that you are amazing and worthy and an absolute badass for finding your way in a neurotypical world!