We have moved a step closer to understanding how mother and baby genes combine to influence birth weight thanks to new research published today in Nature Genetics, in part using Children of the 90s (or Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children/ALSPAC) data. This is an important development as birth weight matters both for the health of both mother and baby at birth and has longer term significance in predicting an increased risk of diabetes, heart disease and blood pressure in years to come.

ALSPAC is part of an exciting and collaborative research consortium - the Early Growth Genetics (EGG) consortium. Formed around a collection of international cohort collections with the addition of leading scientists from all over the world, the EGG consortium has led the way in the analysis and interpretation of genetic contributions to early life events.

This latest research paper (led by a team of researchers from the Universities of Exeter, Queensland, Oxford and Cambridge) is an important contribution to the problem of untangling just how much of the genetic contributions to birth weight come from mother and her baby respectively.

It is important we understand this because babies who are very small or large at birth are more at risk of poor early-life and later-life health than those of average birth weight. The poor health outcomes may be due either to (i) the effects of the womb environment, or (ii) genetic factors inherited by the baby that influence both their growth and their health in later life, or (iii) a combination of genes and environment. A mother’s genetics can influence the womb environment, so by studying her genes, plus the genes inherited by the baby from both parents, we get a better picture of the combination of factors affecting birthweight and better clues to the links with health.

Separating the genetic effects of mother and baby might sound simple but is challenging given that the vast majority of genetic data linked to measures of birthweight are genetic data on the child, with no information about the mother’s genetics. Even when mother’s genetic data are available, splitting up of genetic contributions to birthweight into contributions from mum and child is not easy. However, it has now been possible to address this tricky issue because of (i) the availability of studies like ALSPAC (with its unique resource of paired mother and offspring data on genetics and birthweight) and (ii) the imagination of superb researchers such as Nicole Warrington and David Evans (The University of Queensland Diamantina Institute), who developed new analysis methods to apply to very large datasets like the UK Biobank which collected participants’ own birth weight and genetic data, and the birth weights (but not genetics) of their babies.

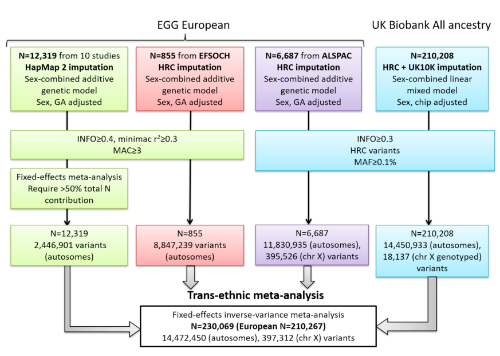

Previous studies brought together as part of the EGG consortium were unable to properly distinguish the direct effects of an individual’s own genotype on birthweight and subsequent disease risk from indirect effects of their mother’s genetics - which itself is delivered at least partially by the womb environment. In this new work, there were a series of stages. Firstly, an expanded “genome-wide association analysis” was done looking at the relationship between the genetics of participants and their own birthweight. Secondly, where data were available, a large study of the same type was done to look at the relationship between mother genetics and offspring birthweight. Lastly, before looking at the possible biological underpinnings of the new findings, further analysis pulled apart the contributions of offspring and mum’s genetic influences – a step implicating both baby and mother biology in eventual birthweight and something novel and very exciting.

In the same study, other methods were used to explore relationships between factors influencing birthweight and health outcomes. For example, both indirect maternal and direct baby genetic effects have been shown to be related to blood sugar measurements and blood pressure and now their relative effects from mother and child could be examined separately. Fascinatingly, results showed that direct fetal genotype effects dominate the shared genetic contribution to the association between lower birthweight and higher type 2 diabetes risk, whereas the relationship between lower birthweight and higher later blood pressure appears to be driven by a combination of indirect mother and direct child genetic effects.

What did Children of the 90s data enable?

One of the key challenges to work like this is that there is simply not enough data available on collections of mothers and children (indeed whole family units) together in order to undertake research like this. As shown in the study design image (Figure 1), the European data feeding into this part of the EGG consortium’s latest work was composed of data from a number of sources. Whilst some collections were larger overall (though measured birthweight by questionnaire) and others together provided data which could be grouped to help sample size, the Children of the 90s data was by far the largest contributor of directly measured mother child pairs in this part of the work. The resource is a major asset to the research community and has a substantial contribution to leading research like this.

Why is this important?

For a long time, there has been a debate around the origin of contributions to birthweight - a feature which itself is importantly related to the health of mother, child and for later life health (at least by association). Hypotheses as to the mechanisms of this have included the effective programming of the new baby whilst it is in the mother’s womb - excluding the notion that the baby itself may be contributing directly to the birth outcome. In successfully separating fetal from maternal genetic effects, this work represents an important advance in genetic studies of perinatal outcomes and shows that the association between lower birth weight and higher adult blood pressure is attributable to genetic effects, and not to intrauterine programming.

Professor Nic Timpson

Principal Investigator, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents & Children also known as Children of the 90s

Dr. Rachel Freathy

Acting Chair and Lead Birth Weight Researcher, EGG Consortium

FIGURE 1. Structure of the latest Early Growth Genetics consortium analysis of mother/child pairs.