The campaign for car drivers to make the switch from leaded to unleaded petrol has been hailed as a major environmental success story in recent years. But despite the dramatic change in our driving habits lead pollution in the environment remains a health hazard and, according to the latest research from Children of the 90s, one to which children are particularly vulnerable.

The research, published today, Thursday, in the on-line edition of the Archives of Disease in Childhood, reveals that raised levels of lead in blood – at even quite modest levels – adversely affect behaviour and educational attainment.

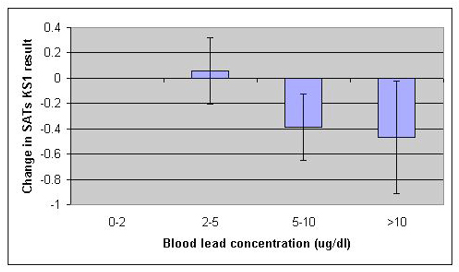

Children of the 90s measured the levels of lead in the blood samples of nearly 500 youngsters at age 2 yrs 8 months and linked these levels to the SATS results of the children at age seven years. After adjusting for the many factors which can affect educational attainment, the analysis showed a clear link between levels of lead in the blood and exam results.

Lead researcher, Professor Alan Emond said his results demonstrated that those children with lower levels of lead in their blood (between 2-5microg/dl) were found to perform significantly better in their SATS that those with blood lead above 5 microg/dl.

Currently, the World Health Organisation has set the international acceptable level of lead in blood – known as the ‘threshold of concern’ - at 10 microg/dl, but Professor Emond is now calling for this figure to be halved to just 5 microg/dl based on these results.

“Exposure to lead early in childhood has effects on subsequent educational attainment, even at low blood levels (5-10 microg/dL). Our results suggest that the threshold for clinical concern should be reduced to 5 microg/dL,” He adds, “We also talked to teachers as part of this research and found that children with lead levels above 10microg/dl were nearly 3 times as likely to show hyperactivity and anti-social behaviour.” (Please see graph at bottom of page which shows relationship between blood lead levels at 2 years and writing scores in the SATS at 7 years).

Children are at the greatest risk because lead is more easily absorbed by their growing bodies and because their tissues are especially sensitive to damage. The main sources of environmental lead include water supplies (lead pipes), old lead paint and soil. Blood lead levels appear to peak between the ages of two and three years – the ages when toddlers tend to put most items (including toys) in their mouths.

“While adults absorb around 10-15% of an ingested quantity of lead, this amount can increase to 50% in infants and young children. This lead is then absorbed into the bone where it can remain for up to 30 years,” he said.

“Lead gets incorporated into the bones and is gradually released into the blood and circulates throughout the body. It interferes with enzymes and affects many systems – including the central nervous system.”

Professor Emond recommends that to reduce lead content in the environment old pipes should be replaced as should old, flaky paint. “Any toys used in the garden, such as buggies and bikes that come into contact with soil should be washed regularly. “

ENDS

Graph:

Academic paper citation:

Effects of early childhood lead exposure on academic performance and behaviour of school age children. Archives of Disease in Childhood. Volume 94 Pages 844-848. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.149955

Notes:

- ALSPAC The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (also known as Children of the 90s) is a unique ongoing research project based in the University of Bristol. It enrolled 14,000 mothers during pregnancy in 1991-2 and has followed most of the children and parents in minute detail ever since.

- The ALSPAC study could not have been undertaken without the continuing financial support of the Medical Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, and the University of Bristol among many others.

- Prof Emond is head of the Centre for Child and Adolescent Health at the University of Bristol.