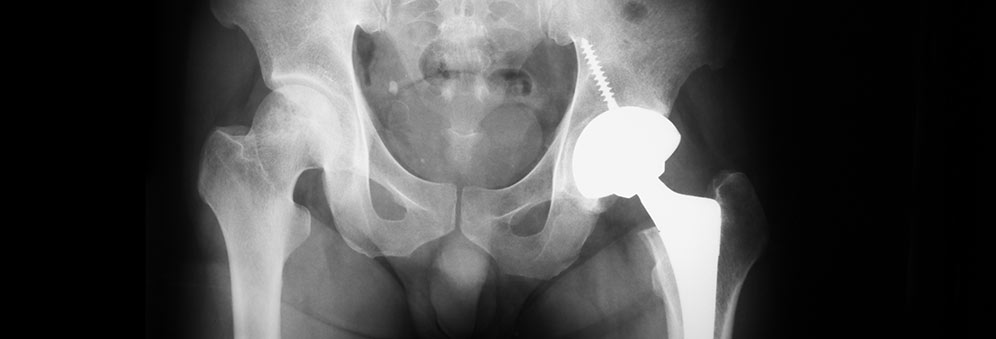

Phasing out all-metal hip replacements

Research revealing the relatively high failure rates of metal-on-metal implants in hip replacement surgery has led to a dramatic decline in their use.

Research in the School of Clinical Sciences resulted in health regulators around the world and manufacturers of metal-on-metal implants taking action to further reduce their use, while reassuring current users that the majority of the implants are safe and working.

Hip replacements are among the most common and successful examples of modern orthopaedic surgery, with an estimated 80,000 operations carried out across England and Wales alone each year. Globally the figure is more than one million.

Metal-on-metal has more failures than alternatives

For the vast majority of patients, the results are overwhelmingly positive, largely eliminating the painful and debilitating effects of osteoarthritis and other less common degenerative conditions. But in 2012, following University of Bristol analysis of a huge dataset collected by the National Joint Registry of England and Wales (NJR), it became clear that a particular type of implant used - metal-on-metal devices - had a much higher rate of failure than alternative options.

Combined with earlier research showing that tiny particles of the cobalt and chromium metals used in those implants were not – as had previously been thought – biologically inert, but were in fact capable of changing cell DNA in surrounding tissues, the work made global headlines when it was published in The Lancet.

“Although the high failure rates are distressing, the majority of metal-on-metal hip replacements have not failed, which is reassuring for patients who have these devices implanted”, says Professor Ashley Blom, from the School of Clinical Sciences. But such is the success of hip replacement in general that the approximately 20 percent failure at 10 years of metal-on-metal implants was unacceptably high.

Analysing the data

The key to establishing that was the NJR database. With records of over 700,000 hip replacement procedures, it represents the largest such dataset in the world. Blom’s group holds a contract to analyse the data, and when they compared surgical revision rates of metal-on-metal implants with other types they showed beyond doubt what many orthopaedic surgeons had been suspecting for some time.

“Surgeons had already started to change their practice,” Blom says, pointing to data showing that the use of metal-on-metal hip implants had declined from 14 percent of procedures in 2008 to less than 1 percent in 2012, when the group’s definitive research was published. “That was the final proof,” he says, with the work in The Lancet serving primarily to bring the problem to the attention of regulators, the world’s media and the public at large.

Health regulators and manufacturers take action

Since then, health regulators around the world and manufacturers of metal-on-metal implants have taken action that has further reduced their use.

In the UK, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) stopped short of banning the devices altogether, reasoning that each specific type of implant must to be judged on its own merits.

In the US, where metal-on-metal implants in hip replacements accounted for as many as 35 percent of procedures in 2008, the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has issued guidance restricting their use and urging follow-up surveillance of patients that have received them. The European Commission has issued similar guidance.

Among manufacturers, key industry players including Smith & Nephew and the Johnson & Johnson subsidiary DePuy Orthopaedics have withdrawn metal-on-metal implants from the market, and Smith & Nephew has issued a field safety notice advising surgeons against their use in some patient groups.

Long-term effects still unknown

Much is still unknown – with Blom admitting that nobody has yet worked out exactly why it is that metal-on-metal implants are much more likely to fail in women than in men, while the long-term effects of low levels of cobalt and chromium ions remain to be seen.

As yet, there is no evidence that the damage to DNA shown by the Bristol researchers to result from metal-on-metal implants has led to a higher rate of cancer in the affected patients. But, as Blom explains, it can take decades for such effects to become measurable in clinical data - and it will likely be many more years before any conclusive results are found.