Responding to child neglect in schools: messages for inter-agency safeguarding practice

This policy report includes recommendations for staff in schools and social workers in child protection services, as well as broader messages for staff in other agencies that work closely with statutory services to safeguard children.

About the research

Child neglect is the most common reason for a child to be placed on a child protection plan in England, and the second most common reason for a child to be placed upon the child protection register in Wales (NSPCC, 2019). Because neglect is often chronic, rather than based on a specific incident, it is difficult to identify whether the care a child is receiving is poor enough to be labelled neglect. This makes it more challenging to provide comprehensive and timely help, that will improve the child’s situation sufficiently.

Schools are vital safeguarding partners within the local authority, having the opportunity to observe children’s interactions with their peers and families over an extended period of time and development. Despite this, little is known about how school staff recognise and respond to children who are living with neglect. This study brings new understanding about the ways in which school staff support children and explores the nature of their inter-professional relationship with children’s services.

I found the relationship between schools and social services very difficult, in that there’s little relationship there. We are with these children for six hours a day or more, five days a week, those children are in our care, yet in my experience we are not called upon or involved as much when there is a social issue.

Background and Context

The study was undertaken at Cardiff University between 2015 and 2018 and funded by Welsh Government through Health and Care Research Wales.

The study was carried out in three regions in Wales (urban, rural and Valleys authority). The regions were selected on three criteria: (i) geographic location, (ii) either a low or high rate of child neglect registrations, and (iii) either a low, average or high rate of deprivation in Wales.

The mixed method study comprised of two phases: Phase 1, statistical case file analysis of children’s social work records [case files were selected upon the following principles: (i) the child was of school age, (ii) the school made the initial referral to the local authority, and (iii) the child was placed on the child protection register under the category of neglect at the initial child protection conference]. Phase 2, 30 interviews with staff in six mainstream schools (including strategic, specialist, teaching, and non-teaching roles).

The findings have important implications for future policy and best practice in the delivery of schoolbased service provision to improve the overall wellbeing of children. The findings also offer broader messages for the development of effective inter-professional relationships, between staff in all universal services and those in child protection services, when safeguarding children living with neglect.

Recommendations for schools

• Schools should recruit strategic staff who demonstrate commitment to developing expertise in child neglect to promote children’s wellbeing within the school setting.

• Head teachers should be supported to establish effective learning communities within their schools to enable staff to develop context-specific knowledge and expertise on how to effectively respond to child neglect within a school setting.

• All school staff who live within, or have extensive knowledge of, the local community should be provided with opportunities to provide insights into the lives of children who are suspected of living with neglect.

We have a greater depth of knowledge about a family and then somebody from Social Services goes along once, who doesn’t know the area or the family, they make this judgment obviously on this one visit!

Recommendations for children's social workers

• Social workers should routinely collect core data on children’s electronic case files to improve recording practice and inform further research in this area.

• Social workers should use the local authority’s threshold guidance document as a shared tool for reflective discussion with schools to inform decision making, and develop a ‘shared language’ to articulate concerns.

• Social workers should routinely provide feedback to schools on the outcome of referrals made to child protection services and the rationale for their decision not to intervene.

• Social workers should ensure that Child Protection Conferences are not planned during school holidays, and that information is shared with new schools where children are transitioning to secondary education.

The social worker sees things from a different aspect and perspective to the teacher.

Recommendations for inter-agency practice

• Strategic and managerial staff should cultivate understanding around the barriers which impede successful inter-agency collaboration.

• All practitioners should build trusting working relationships with individuals in partner agencies.

• Informal and formal opportunities should be made available to all staff to support knowledge development of partner agencies’ terms, roles, approaches and methods of working.

• All staff should have the opportunity to spend time in partner agencies to develop expertise across services through informal day visits, or formal secondments/co-location of services (with counterparts in statutory or universal services).

• Training on child neglect should be undertaken in a multi-disciplinary setting.

• The role of the School Social Worker responds to interprofessional barriers in schools and child protection services and should be expanded to all authorities in Wales.

• The local authority’s threshold guidance/matrix document should be used as a tool for reflective discussion across services, to inform decision making and foster a ‘shared language’, so that schools can articulate the concerns underpinning their referrals.

Maybe there are other concerns… they [social workers] get to see outside of the school that we wouldn’t know about… we only see, and we only deal with the ones we see in school.

Key Findings

The study’s findings are connected by the overarching theme of ‘unevenness and difference’: differences in case file data, differences between practice in schools, and differences in practice across the two fields of responsibility: school staff and social workers.

Phase 1: Social work case file analysis

• Statistical analysis revealed that more boys (58%) were identified as living with neglect than girls.

• Children living with neglect had a mean age of 9.6 years.

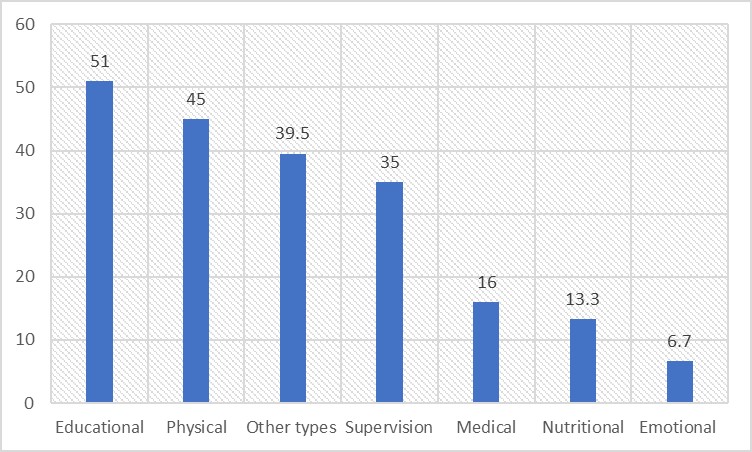

• In their referrals, staff most commonly cited concerns about educational neglect (this included school attendance, punctuality and lack of parental engagement), followed by

physical neglect.

• In over 40% of the sample, schools provided support (financial, practical and emotional) to families, commonly providing clothing, food and basic toiletries to pupils either prior to or during statutory interventions.

Bar chart illustrating the types of neglect most commonly reported within schools’ referrals to child protection services. The category of ‘Other’ refers to other types of maltreatment which are not neglect, such as instances of physical or sexual abuse.

Phase 2: Interviews with school staff

In phase two the principal finding was the contrasting practices between school staff and social workers.

• School staff relied upon visual indicators of neglect that could be seen during the school-day and had different understandings about what they felt was ‘neglectful’ parenting.

• The use of professional language and statutory operational categories of neglect in statutory services resulted in difficulties with inter-agency communication and information sharing, particularly when school staff completed safeguarding referrals.

• School staff described social workers as ‘powerful agents’ or ‘experts’, and talked about a lack of professional confidence to identify neglect or challenge statutory assessments or decisions, despite often holding more information about a child.

• Nearly all school staff reported the challenging nature of their inter-professional partnership with social workers in child protection teams and the impact this had upon their ability to respond to neglect effectively.

• Although there were cultural and organisational differences between schools, good practice was demonstrated in schools which took a proactive approach to neglect, offered a positive learning environment for staff to develop ‘neglect-expertise’, and those where staff had established positive relationships with families.

• An important finding from the study was that these factors were consistently evident in smaller-sized schools (primary and secondary) when staff were identifying and responding to children living with neglect.

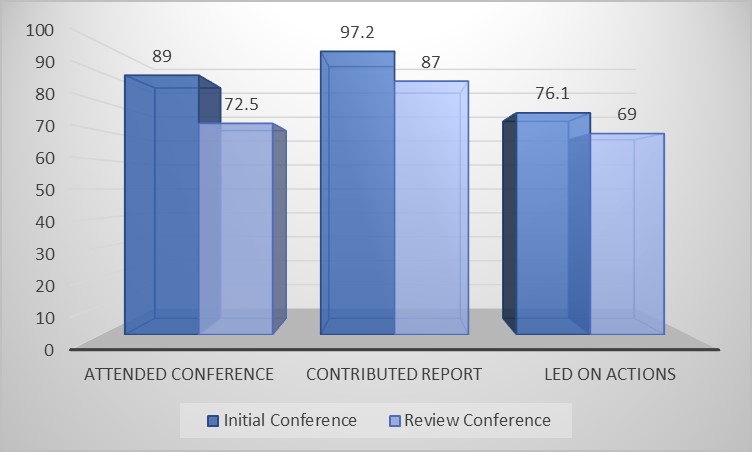

Bar chart illustrating the school’s attendance, involvement, and responsibility for leading on actions on the child’s plan, firstly at the initial child protection conference and secondly at the review conference (3 months later). The chart demonstrates a decline in school staff (i) attending review conferences (ii) sharing reports at review conferences, (iii) and taking less responsibility for ongoing actions on the child’s child protection plan.

And that is one of the criticisms, we don’t get feedback on referrals. We only get feedback if they’re [Children’s Services] picking it up. We don’t get the letter to say “thanks very much for your referral, but on this occasion we’re not [investigating]”.

Problematic Data

• Another important finding was the problematic nature of the statistical data: challenges were practical (not achieving the desired sample size due to low regional populations) and numerical (large amounts of missing data on case files).

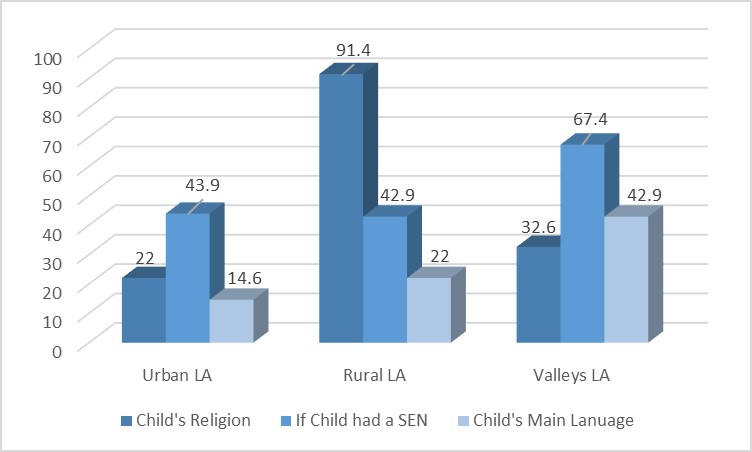

• The level of information recorded in the case files varied, both within and between the three participating local authorities. In particular, information was missing on the child’s religion (46%), language spoken (27%) and whether they had a statement of educational need (52%).

Bar chart illustrating the amount of missing data on children’s social work case files (split by local authority area) - across three variables: (i) the child’s religion, (ii) whether they had a Statement of Educational Need, and (iii) main language spoken.

Further information

Sharley, V. (2019). ‘Identifying and Responding to Child Neglect in Schools: differing perspectives and implications for inter-agency practice’. Child Indicators Research. 13, pp551–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09681-z

Sharley, V. (2018). ‘Identifying and Responding to Child Neglect in Schools’. PhD Thesis. Cardiff University. http://orca.cf.ac.uk/id/eprint/115691

This document summarises independent research funded by Welsh Government through Health and Care ResearchWales and undertaken at Cardiff University.

The views expressed in this document are those of the author and not necessarily those of Health and Care Research Wales or the Welsh Government.

Authors

Dr Victoria Sharley, School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol