Mayoral governance in Bristol: Has it made a difference?

The directly elected mayor model of place-based leadership was introduced into Bristol following a citizen referendum in 2012. The Bristol Civic Leadership Project is examining the impact of this new model on the governance of the city. This report assesses the performance of mayoral governance from 2012-20.

While well-established internationally, the directly elected mayor model of place-based leadership is still relatively new in the UK. Opinions on this model of governance are often polarised. Supporters claim that the mayoral model delivers streamlined decision making, and more visible, more accountable, and ultimately more effective city leadership. Critics argue that it can lead to an over centralisation of power, weakening the role of councillors and undermining confidence in representative local democracy.

The Bristol Civic Leadership Project, launched in 2012, set out to provide evidence on what difference the mayoral model actually makes to the governance of a city, and to identify ways to improve the performance of the model. A collaboration between the University of Bristol and the University of the West of England, Bristol, this research involves representative surveys of citizens and of civic leaders, including councillors, public managers, and leaders from the community, voluntary, and business sectors, and workshops and focus groups with actors from inside and outside local government.

In 2012, after a referendum narrowly endorsing the move to mayoral governance, citizens elected George Ferguson, an independent politician, as the first directly elected mayor of Bristol. In 2016 Marvin Rees, the Labour Party candidate, defeated Mayor Ferguson, and will face the voters again in May 2020. Our research is not focused on the performance of the individuals who have served as mayor of the city. Rather our aim is to illuminate the strengths and weaknesses of the mayoral model itself.

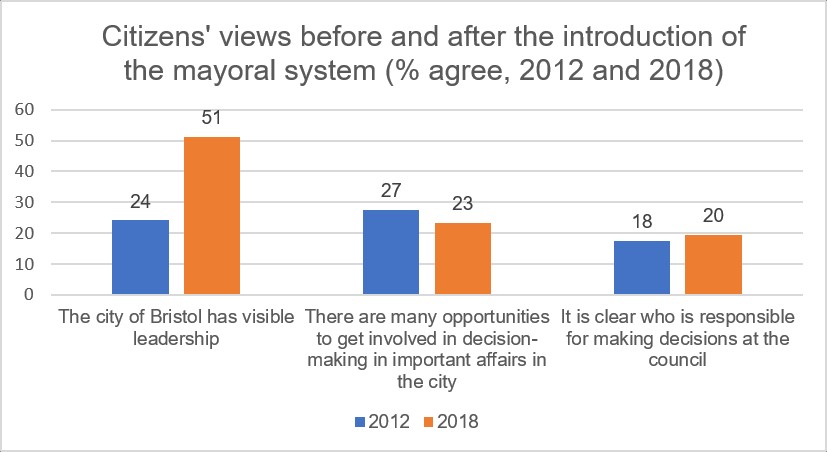

This action research suggests that there has been a startling increase in the visibility of city leadership. There are, however, significant differences of view on how well the model has improved processes of representation and decision-making within the city.

The Government believes that elected mayors can provide democratically accountable strong leadership which is able to instigate real change for the benefit of our largest cities. Mayors will be clearly identifiable as the leader of the city and will have a unique mandate to govern as they will be directly elected by all local electors. People will know who is responsible for a decision and where the buck stops.

Leading in the City

Visibility of city leadership

The introduction of the mayoral model has resulted in a spectacular increase in the visibility of city leadership. In 2012 24% of citizens thought the city had visible leadership, whereas in 2018 this figure rose to 51%. Our evidence shows that all socio-economic groups within the city agreed that the visibility of city leadership has improved dramatically in the 2012-18 period.

Civic leaders from outside government, those working in the community, voluntary and business sectors, are even more positive. Some 25% thought that the city had visible leadership in 2012, a figured that soared to 91% in 2018. Even councillors, many of whom opposed the mayoral model, recognise that mayoral leadership has increased the visibility of the city leader, albeit marginally (56% to 58%).

I think the key advantage of the mayoral model is that it delivers identifiable leadership, someone who can speak for the city, not just for the council… someone with a clear mandate from the whole of the electorate. And it’s a model that has been proven elsewhere.

A vision for the city

Mayoral leadership has led to a more broadly recognised vision for the city. In 2012, 25% of citizens agreed with the statement: ‘The leadership of the council has a vision for the city’. This rose to 39% in 2018.

Several interviewees stated that mayoral governance has underpinned longer-term policy development for the city, and the One City Plan, which sets out a detailed vision for Bristol in 2050, was praised by many respondents.

I think it would have been very hard to develop the One City Approach and the One City Plan if these efforts were not spear headed by a mayor… it is a very brave initiative to, in effect, take on wider responsibilities… yes, it is a work in progress but I don’t think this initiative would have happened without a directly elected mayor.

Representing the City

Representation of the city in the wider world

The first two mayors of Bristol have made considerable efforts to promote Bristol on the national and international stage. For example, Mayor Ferguson was able to use Bristol’s award of European Green Capital 2015 to project the profile of Bristol as an eco-friendly city to a global audience.

Mayor Rees built on this legacy and has sought to increase the international stature of Bristol through a range of important initiatives. For example, Bristol hosted the Global Parliament of Mayors summit in October 2018 and, in 2019, the European Union designated Bristol as one of the six most innovative cities in Europe.

Our surveys show differences in perceptions between sectors of how well the city is represented in the wider world. In 2018, 57% of leaders from the community, voluntary, and business sectors, and 64% of public managers, agreed that the leadership of the council is effective in representing the council in national and international arenas. However, only 33% of councillors, and only 32% of Bristol’s citizens agreed.

Representation in the city

Many councillors feel that, under mayoral governance, they have less capacity to represent the needs of their community effectively. Councillors are much less inclined to consider that the needs of their community are well represented in decision-making in the city (58% in 2012, compared to 17% in 2018), or that citywide views are well represented by the council (58% in 2012, 28% in 2018). Citizens perceive little difference in these matters. Some 16% thought that their community was well represented in 2012, and 14% in 2018; 18% considered that citywide views were well represented in 2012 compared with 15% in 2018.

Decision Making in the City

In the period since 2010, central government has imposed drastic spending cuts on local authorities across the country. A consequence is that locally elected politicians, including directly elected mayors, find that their decision-making capacity is hugely constrained.

Getting involved

'The biggest problem is the lack of resources for the mayor. They need a tax raising power, or sufficient money to be able to do the things that they want to do or are being asked to do. More money needs to be devolved to cities to enable them to tackle long-term issues.' Bristol voluntary sector leader

Under conditions of austerity, the City Council made the difficult decision to abolish neighbourhood partnerships and scale back area-based decision-making in the city, and this has weakened the influence of neighbourhood voices in the governance of the city. However, several innovations in city decision-making processes have been introduced under mayoral governance. For example, Mayor Ferguson launched an ‘ideas lab’, and Mayor Rees introduced a One City Approach in an effort to expand the range of stakeholders involved in policy development via City Gatherings and other means. Both mayors have given very well-attended annual ‘state of the city’ addresses.

Fewer citizens in 2018 consider there are many opportunities to get involved in decision-making in the city (23% in 2018, compared to 27% in 2012). Councillors perceptions of involvement have plummeted on this measure, from 65% in 2012, to 17% in 2018.

'Prior to the mayoral model, we had different administrations, and we never agreed on everything, but there was discussion, and there was opportunity for opposition to actually bring things forward, and say, “well what about this”. And quite often they were actually listened to.' Bristol councillor

Clarity around who is responsible for making decisions

Timeliness, trust, councillors and decision-making

Citizens’ views on timeliness of, and trust in, decisionmaking are both lower in 2018 than in 2012. In 2018 15% of citizens trusted the council to make good decisions, and only 8% of them believed that decisions were made in a timely way by the council. These figures were down from the already low scores in 2012 of 19% and 13% respectively.

Many councillors perceive the mayoral model as limiting their capacity to scrutinise and hold the leadership of the council to account. In 2012, 51% of councillors agreed that they provided an effective check on council leadership, but by 2018 this fell to 22%.

Policy Implications

The introduction of mayoral governance in Bristol has boosted the visibility of city leadership. The mayor of Bristol is a high-profile public figure able to convene important stakeholders. Leadership in local government has long been criticised for failing to produce visible leaders, and place-based leadership is surely enhanced when members of the public are able to identify those exercising it. Supporters also argue that the model delivers a secure four-year term for the leader. This can enable the development of longer-term policy initiatives such as the One City Plan, as well as more consistency in decision-making. Coupled with the enhanced legitimacy of a direct mandate from voters and the concentration of powers in the mayor, the model offers a potent vehicle for strong city leadership.

Criticisms of the directly elected mayor model emphasise that there is an over-concentration of power in the hands of a single leader. Moreover, this research highlights that the mayoral model of governance has not yet had a positive impact on the wider system of representation and local decisionmaking in Bristol, with citizens and councillors reporting a weaker capacity to represent communities and scrutinise and hold the elected mayor to account.

Also, and importantly, central government’s policy towards local government is critical. The transition to mayoral governance in Bristol has coincided with a sustained and drastic set of cuts to the funding of local government. The over-concentration of power in Whitehall places huge constraints on the ability of local leaders, and the system of which they are a part, to make strategic choices and exercise effective place-based leadership.

The following matters should be addressed by central and local government.

- Powers and funding: If central government wants to deliver successful mayoral governance in England, it needs to devolve far more powers and fiscal autonomy to local areas so that elected local leaders can exercise decisive place-based leadership.

- Strengthening the role of councillors: As a priority the role of councillors in the mayoral system of governance in Bristol should be reviewed. Councillors provide a vital link between the city and their communities, and to make the most of that link, they must be influential players in the governance system. New roles for councillors, for example, acting as community catalysts, should be explored.

- Addressing democratic deficits: To facilitate greater involvement in decision-making, consideration should be given by elected mayors, councils and communities to developing more opportunities for citizens to participate more directly in decision-making, either indirectly through representative councillors, or directly through more participatory engagement.

- Working to improve trust and understanding Public trust in local decision-making is a longstanding issue in UK local government that has not been improved by the introduction of mayoral governance. In the key areas of clarity and timeliness of decision-making, steps should be taken to promote understanding of who is making decisions, and by what timescale, to improve public confidence in decision-making in mayoral authorities.

Policy Report 55: March 2020

Mayoral governance in Bristol: Has it made a difference? (PDF, 621kB)

Authors

Contact the Researchers

Further Information

Further publications and details of our research can be downloaded from bristolcivicleadership.net.