Managing change without the use of external consultants: how to organise consultant managers

Management consultancy should no longer be seen simply as something done by influential outsiders, but as part of the toolkit of any manager responsible for delivering change.

About the research

Management is changing. It is becoming less explicitly hierarchical and more ‘market and change’ oriented. This has been happening through flattening organisational hierarchies, using new technologies and the rise of management education. Organisations are speeding the process up by internalising a model of management based on external management consultancy. New ‘consultant managers’ include specialist internal staff who provide change advice, facilitation and management, typically on a project/programme basis. These individuals see their role as associated with a form of consultancy, even if they use various job titles.

This may not be good news for external management consultants, but senior managers could look to harness the opportunities this new development presents, especially when there is pressure not to use external consulting. While some consultant managers operate individually, most work in different organisational units responsible for achieving change across diverse organisations and sectors.

This policy report sets out four main options for senior managers and civil servants seeking to organise change internally – the TESI model - and considers the broader implications for management occupations, such as Human Resource Management (HRM) and Information Technology (IT) managers, who may wish to develop their role in change management.

Image by Johnny Magnusson

Implications for management occupations

- Any occupational group considering reframing their role around the notion of the consultant manager must be clear about how they offer a distinctive insight into change.

- Organisations should consider internalising management consultancy practices as a way of saving money and making better use of internal resources.

The TESI model of organising change internally

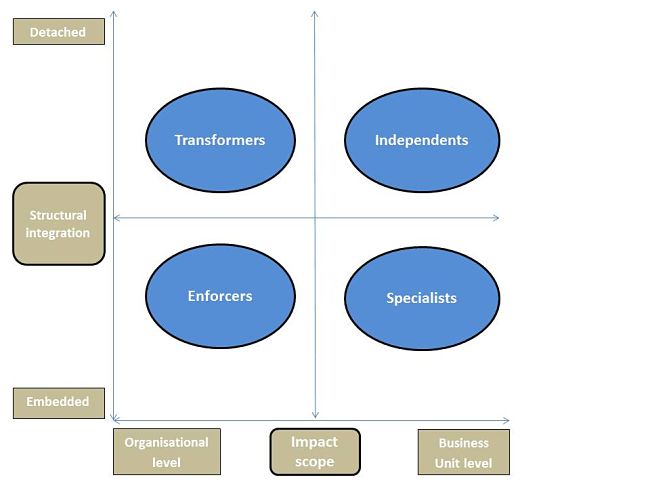

The ‘TESI’ model represents the four dominant types of change delivery unit in which consultant managers operate: Transformers, Enforcers, Specialists and Independents. Each one addresses particular strategic pressures and can be distinguished along two dimensions: structural integration (that is, embeddedness in organisational structures) and impact scope (that is, whether change mostly occurs at organisational or lower levels such as a department). See diagram on page 4.

1. Transformers

‘Transformers’ are units established with the purpose of achieving large-scale change. Often such change is strategic, leading to broad and pan-organisational impacts. These units tend to be detached from particular business units or departments. They contain a combination of internal specialists seconded from operational areas and former external consultants with a strong project management focus.

One local authority used individuals with consultancy expertise and those with extensive organisation-specific knowledge in a ‘Transformer’ unit, and achieved a wide-ranging programme of cost savings.

Establishing a Transformer unit does carry risks. For example, a unit with broad impact scope is likely to have a high profile in the host organisation. This may mean that these units face suspicion from operational managers keen to retain control over initiatives in their own areas. This can create disputes over responsibility for impact and threaten the potential benefits of the change. Also, tensions can be exacerbated by the pressure to adopt a more directive approach to change given that they often have limited timescales in which to achieve impact.

2. Enforcers

Enforcers also have a pan-organisational focus, but they are more likely to be embedded in the organisational hierarchy, most notably in the form of a support unit for chief executives (CEOs). Their role is to help CEOs translate strategic goals into specific projects and enforce a form of central control to ensure consistency. Consequently, Enforcers often have a quasi-policing role and are used to signal the strategic priorities of senior management across the organisation. In our research, it was most common for Enforcers to contain former external consultants whose relative independence from (other) sectional interests meant that they were more likely to be considered as trusted advisors to senior management.

One CEO referred to his Enforcer unit (Transport) as ‘the clever guys down the corridor’ and used their existence to threaten other managers with investigations into key operational processes.

The risk with the Enforcer unit is that, again, it can be regarded with suspicion amongst operational managers, leading to antagonistic relationships. Enforcer units may also be subject to the whims and short-term interests of a particular senior manager.

‘Being seen as the eyes and ears of the deputy CEO could close as many doors as it opens.’ - Consultant manager from an Enforcer unit (Financial Services)

3. Specialists

Consulting units do not always manage change at the organisational level. If more incremental change is required, a Specialist change delivery unit is an option. These have a more limited (although not necessarily less important) impact scope because they are embedded in organisational structures, often in service functions such as IT or HR. They are staffed by subject-matter experts who are likely to see opportunities to manage change through consultancy practices. They will also be funded through existing departmental budgets and have the expressed purpose of seeking to offer advice and guidance where needed. In this way, Specialists present opportunities to develop the status and credibility of service functions by combining distinctive knowledge with change management insights.

Risks or challenges relating to Specialist units are that they may struggle to overcome long-standing assumptions about service functions. In this research, Specialists with an HR focus faced particular difficulties because they found that they had to overcome traditional, negative perceptions of their role as well as that of management consultancy! The sometimes narrow focus of Specialists could also mean they offered fairly limited problemsolving solutions, particularly if change issues did not map directly onto their interests.

Key findings

- For management occupations, the use of internal change units presents an important opportunity to enhance their status and credibility.

- However, change units are often transitory and experience uncertainty about their role and value. Change management can be a crowded domain, with other occupational groups seeking to establish jurisdiction and control over change agendas.

- The emerging role of the consultant manager presents organisations with a challenge of how best to use, develop and adapt their skills and capabilities.

- The need for change is often well understood or, at least, confidently asserted, but allocating resources and identifying the expertise available to best drive this change is more challenging.

4. Independents

Where managers identify the need for the persistent presence of a more generalist change unit, Independents are an option. The impact scope of these units tends to be localised as they deliver change through specific projects within business units or departments. At the same time, Independents are detached from core operational areas and managerial hierarchies. In this way, Independents most closely resemble external consultancies because they are required to source their own work and to become self-funding. This is a clear point of contrast to the other units, which are designed to deliver pre-defined projects and are not subject to the same level of resource constraints. As with Transformers, Independents can combine former external consultants and managers from within the organisation in an attempt to benefit from both the ‘exotic outsider’ status and detailed insider knowledge.

An Independent Unit in a global financial services firm recruited ex-management consultants without sector knowledge in order to diversify their role in change delivery. The Unit Manager explained: ‘We’ve hired some people from the external consulting world to bring a view on what other methodologies there are’.

Independents may offer a lower-risk form of change delivery unit in that they have some autonomy over their work. However, the need to guarantee a pipeline of work may mean that the unit’s focus shifts to fairly insignificant projects with the result that they may lose credibility. They can also find that a great deal of their role is involved with ‘relationship management’ activity to ensure that they are the first choice for change delivery work within the organisation. Problems may also emerge from complex funding arrangements as well as their extreme dependence on client resources and preferences in an internal market. But this can also be an incentive for Independents to work with external clients, something that successful units can use to enhance their status.

‘Part of the reason we’ve got so much credibility is that we’re not only internally focused, we also work outside the organisation.’ – Consultant Manager from an Independent Unit (Healthcare)

The figure above shows the TESI model of change delivery units.

Further information

See the authors’ latest publication: ‘Management as Consultancy’

Read Professor Sturdy’s blog on the PolicyBristol Hub: ‘The demise of management consultancy and the rise of the consultant manager?’

Authors

Professor Andrew Sturdy, University of Bristol, UK

Dr Nick Wylie, Coventry University, UK

Policy Report 06: 2016

Managing change without the use of external consultants (PDF, 199kB)

The whole purpose of creating the (HR) consultancy group was to be able to focus on value-add activities and not get caught up in the transactional day to day stuff.

Contact the researchers

Professor Andrew Sturdy

University of Bristol:

Andrew.sturdy@bristol.ac.uk

Dr Nick Wylie

Coventry University:

nick.wylie@coventry.ac.uk