Implementing the ‘Liberty Protection Safeguards’ is an urgent priority

In England and Wales, over 300,000 people are deprived of their liberty in connection with their care arrangements, yet their human rights are not well protected.

When care arrangements are made in the ‘best interests’ of people who lack ‘mental capacity’ to make decisions for themselves, they sometimes involve restrictions on people’s everyday rights and freedoms. Although such restrictions are usually intended to keep a person safe or deliver care and treatment, if it involves ‘continuous supervision and control’ and the person is ‘not free to leave’, then the law requires further safeguards to protect their human rights. These are currently provided under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 ‘deprivation of liberty safeguards’ (DoLS), which provide an ‘independent check’ to keep restrictions to the minimum necessary, to fully consider the wishes and feelings of the person and their loved ones, and enable people or their family to challenge any restrictions they are unhappy with.

Unfortunately the DoLS system is not working: it is too complex, too costly, and does not properly protect people’s human rights. Councils, who administer the system, are struggling to cope. The current system does not apply in all situations where safeguards are needed.

In 2017 the Law Commission proposed a new system – the Liberty Protection Safeguards – that would be more proportionate, flexible and improve protection of rights. Despite considerable preparatory work on implementing this new system, in April 2023 the Government postponed it until ‘the next Parliament’.

The future of these safeguards is uncertain.

Implementing new and effective safeguards must be a key priority for any government after the next election. This will better protect the human rights of individuals - and their families - drawing on care and support. It will also alleviate the pressures of the current system on local authority social services.

Background

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) came into force in 2009. They apply in care homes and hospitals to those aged over 18. They were introduced after the European Court of Human Rights ruled that a learning disability hospital had violated an autistic man’s right to liberty when it admitted him ‘informally’, despite his carers’ objections, leaving them without any accessible means to challenge his admission and bring him home.

Today DoLS mainly impact older adults, particularly people living with dementia, as well as some younger people with learning disabilities, brain injury and other mental disabilities. When DoLS operate properly, they can deliver valuable protection. See case studies.

Figure 1: Overview of the deprivation of liberty

Figure 1: Overview of the deprivation of liberty

Case study: a right to homelife

In 2010 a local authority refused to let Steven Neary, a young man with autism and learning disabilities, return home to live with his father. His father requested that his son return home, but his campaign was not effective until the DoLS were finally

implemented by the council. This enabled him to access independent advocacy, and eventually the Court of Protection. The court concluded that Steven’s detention in a care home had violated his right to home and family life, and ordered that he be allowed to return to live at home. Steven Neary’s father wrote that without the DoLS, Steven and his family would have been unable to challenge the local authority’s decision.

Case study: Mr P and Fluffy the cat

Mr P, a 91 year old retired civil servant and former RAF gunner, lived with Fluffy, his cat, in his own home of 50 years. The local authority had moved Mr P into a care home following safeguarding concerns, but they had done so without any independent oversight of this decision making (unlike child protection, adult safeguarding does not operate within strict statutory parameters, setting clear limits and independent checks on safeguarding measures). The DoLS enabled Mr P’s friends to challenge this in the Court of Protection, which found the safeguarding concerns unfounded and ordered that he be returned home.

Key safeguards

- An 'independent check' on the care arrangements by expert professionals

- Exploring less restrictive alternatives

- Imposing conditions on authorisation can reduce restrictions

- Information, representation and advocacy to help people understand and exercise their rights

- A right to request reviews or challenge restrictions in the Court of Protection, including legal aid.

What are the problems with the deprivation of liberty safeguards?

Local authorities administer the DoLS in England (outlined in Figure 1). They apply whenever a person is considered ‘deprived of their liberty’, and this is defined by the courts. A 2014 Supreme Court ruling – Cheshire West - adopted a broader definition than earlier cases. The number of DoLS applications increased from under 20,000 a year in 2013 to over 300,000 in 2022-23. Local authorities cannot keep up with demand; there is a backlog of 126,100 unprocessed applications and almost 50,000 people died waiting for safeguards to be applied. A further 58,000 people are deprived of their liberty in settings where DoLS do not apply (e.g. supported living), many without any safeguards at all.

Post-legislative scrutiny by the House of Lords Select Committee on the Mental Capacity Act in 2014 concluded that DoLS were ‘not fit for purpose’: they were too complicated, costly and resource intensive, yet offered weak protection of human rights, whilst families found them confusing.

Development of the Liberty Protection Safeguards

The Law Commission developed the LPS to replace the DoLS. They are intended to be more flexible, proportionate, and streamlined, and target resources to situations with the greatest need for independent scrutiny. Unlike DoLS, the LPS would apply in any setting (including supported living), and provide safeguards for younger people in care, aged 16 and 17. The Government legislated for the proposals (Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019) and consulted on implementation plans.

Despite extensive preparatory work, widespread sectoral support, and the government 'completely accepting the need’ to move to the LPS, implementation has been repeatedly delayed. In April 2023 the Government postponed the LPS until the ‘next Parliament’; implementation will therefore fall to a new government after the next General Election.

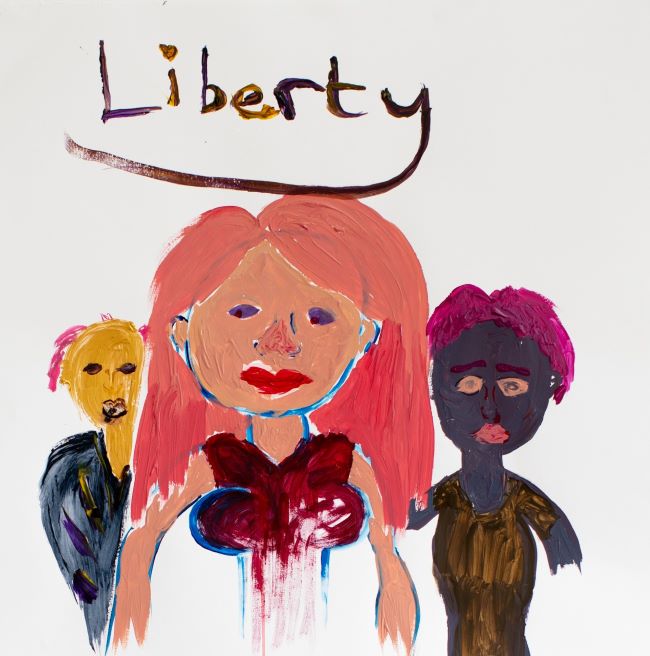

© Grace Currie: artwork; Helter Skelter: photography.

The Cheshire West 'acid test'

The Supreme Court ruled a person is ‘deprived of their liberty' if the following criteria are met:

a) they lack the mental capacity to give a valid consent to their confinement, and

b) they are ‘not free to leave’ and they are subject to ‘continuous supervision and control’.

This test applies wherever a person might be cared for, even in domestic settings. It also applies regardless of whether the person appears ‘content’ with their care, and those caring for them believe it to be necessary and in their best interests.

Recommendations

• Older and disabled people urgently need better protection of their fundamental human rights. Many experience excessively restrictive care (especially following Covid), whilst families report not being fully involved.

• Most people who are deprived of their liberty in non-traditional settings where DoLS do not apply, such as supported living, have no independent oversight or safeguards at all. Due to the inflexibility of DoLS and under-resourcing, local authorities are currently left having to work out – in the words of the Joint Committee on Human Rights - ‘how best to break the law’.

• The next government urgently needs to progress work to implement the LPS to improve human rights protection for all.

• Some issues require further thought, particularly around domestic settings and the interface with the Mental Health Act 1983. But this cannot detract from the importance of securing these rights for individuals who draw on care and support, and their families.

A gilded cage is still a cage.

Further Information

Series, L.2022. Deprivation of Liberty in the Shadows of the Institution (Bristol University Press).

Series, L. 2019. ‘On detaining 300,000 people: the Liberty Protection Safeguards’. International Journal of Mental Health and Capacity Law 25: 79-196.

Joint Committee on Human Rights. 2018. ‘The Right to Freedom and Safety: Reform of the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards.’ HC 890, HL paper 161.

Department of Health and Social Care and others. 2022. ‘Closed Consultation: Changes to the MCA Code of Practice and implementation of the LPS’.

Main Image credit: © Grace Currie: artwork; Helter Skelter: photography.

Author

Dr Lucy Series, University of Bristol

Policy Report 90: Nov 2023

Implementing the ‘Liberty Protection Safeguards’ is an urgent priority (PDF, 1,703kB)

Contact the researchers

Dr Lucy Series

lucy.series@bristol.ac.uk