Health Inequalities in Inner City East Bristol: Community Strength in Challenging Times

Our research shows that everyday life has become more difficult for those who are already vulnerable to health inequalities. Residents are well-informed about how to look after their health and are highly resourceful in creating healthy habits. However, stress, cost, transport and stretched services remain barriers to health.

About the research

In the absence of well-funded and accessible public services, community organisations are taking on an increasingly important role in supporting people to look after and improve their health, including:

• Accessible ways to find out about and take part in self-care;

• Groups and activities that offer routine, structure, learning and inclusion;

• People who listen and treat them with dignity and respect;

• Opportunities to connect with community, nature and spiritual heritage.

Healthy neighbourhoods and a strong community sector are essential to allow people to support their own health, and to reduce health inequalities. Policy makers need to address urgently the pressures on public services which generate long waiting times and limited services, and are impacting the most disadvantaged in our city. It is vital to recognise and resource community health initiatives which are mitigating the current crisis, providing residents with opportunities to learn, connect, and be heard

This research is part of an ongoing collaboration between Wellspring Settlement and the University of Bristol to develop better understanding of community perspectives on health. We used the methodology of co-production, working with a team of community researchers with expertise in health to make sure that community voice and experience were at the heart of the research design. The aim of the research was threefold: to explore the lived experience of health inequalities in the inner city and to create a platform for community voice; to describe existing assets in the community; and to inform the development of health creation in a community setting. The next phase of the project, beginning in summer 2024, will work with Bristol City Council to develop health creation networks in the locality, based on what residents would like to see in their communities and recognising the role of grassroots activities to support people managing their own health and wellbeing. Between April and November 2023, the project team ran art sessions for 63 participants in Inner City East Bristol. Participants took part in art-making activities and discussions, focused on questions informed by an assets-based community development perspective and social model of health: What stops you prioritising your health? How do you grow your health? What do you do for your health that you deserve a medal for? What do you need in your neighbourhood to be healthy? The images and quotes in this report are from these sessions. Recruitment prioritised residents from South Asian and Black African and Caribbean communities, those experiencing anxiety, depression, pre-diabetes and diabetes, and those living in the Barton Hill tower blocks. We partnered with Dhek Bhal to engage the South Asian community. As fewer men signed up for the activities, we also worked with the Wellspring Settlement men’s group. 81% of participants were from a global majority background (people of colour). 67% were female and 33% were male.

The situation

Present challenges are exacerbating existing health inequalities related to social and economic deprivation, race, gender, disability and sexuality. The life expectancy gap between the least deprived and the most deprived areas of Bristol is 9.9 years for men and 6.9 years for women (Our Future Health, 2022). Such inequalities come about because people don’t have access to the building blocks or ‘social determinants’ (Marmot, 2010) of good health, such as good quality housing, environment, and relationships, financial stability, freedom from discrimination, as well as access to timely health care. In this context, residents are having to draw deep on their own resources, and on the support that is provided within the community (see Locality, 2023).

Key Findings

1. Community understandings of health

Participants in our research value their health and look after it. They have well developed self-care routines, including:

- Healthy eating: portion control, adapting traditional recipes, eating vegetables, salads, seeds. ‘Fresh fruit and vegetables make me happy!’

- Regular exercise: ‘Exercises every morning, walking is most important for older men, dropping weight.’

- Family and friends: ‘it’s the most important thing for me to be happy.’ ‘We joke and laugh which is important for my mental health.’

- Many people identified having a routine as helpful, including prayer, walking, working, volunteering and going to groups. ‘I push myself to volunteer and work, even when I don’t know how I’ll cope, because I know that having a purpose in life is important for wellbeing’

- Creating a balance. ‘Balancing being active with not doing too much’.

- Religious/spiritual practices: ‘When I do my spiritual practice in the morning it puts me at ease, calms me and gives me energy.’ ‘If my mind is happy, I’m happy.’

- Learning through courses and on your own. ‘I have a love for learning, a big passion for it…it’s good for my motivation.’

- Having a positive kind mentality to yourself. ‘When you’re down you have to talk nicely to yourself, to your inner child.’

2. The lived experience of austerity

The cost of living crisis, precarious housing and stretched services are significantly increasing stress levels in the community.

- Participants report accommodation which is unsafe, noisy, dirty, stressful and unstable, particularly council-owned flats. ‘The gate’s always broken and the buzzer doesn’t work. My home isn’t safe.’ ‘People with poor mental health who are not supported well by services affect the mental health of their neighbours.’

- It can be difficult for people with a disability to access public transport. ‘They [bus drivers] don’t like me getting on the bus as they lose time. This loses me confidence in getting on the bus.’ This results in limited access to services such as pharmacy, dentistry and hospital appointments.

- The cost of living crisis creates both stress and barriers to looking after health: ‘We have the same meal, pasta, all week as it’s cheap.’ ‘If you could buy your own mental health support you could sort it out on your own.’

- People with caring responsibilities are particularly likely to feel overwhelmed: ‘Everything is going on all at the same time and I need to be like an octopus.

‘I don’t want to be in survival mode all the time, it’s exhausting.’ (Alisha, 36)

Participants told us that they lacked trust in the health service, experiencing power imbalances, difficulties with access, and long waiting times. They described frustration at being dependent on inadequate services and a strong sense of not being heard.

- Participants reported problems with service provision including long waiting lists and lack of continuity of care. Being repeatedly turned away resulted in feeling alone and despairing: ‘I’m the only person who keeps me alive and that’s very sad.'

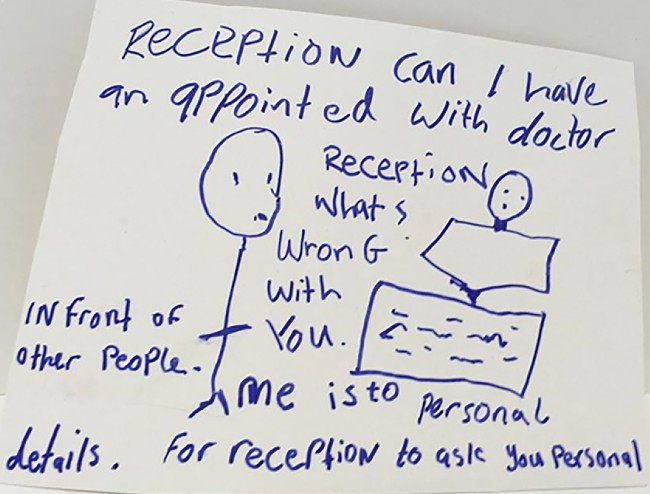

- Participants wanted more joined-up care. 'Medical staff don't have the training or ability to help you so you can't access appropriate care.' They were also concerned about lack of privacy e.g. being asked to share confidential information in public spaces when making a GP appointment.

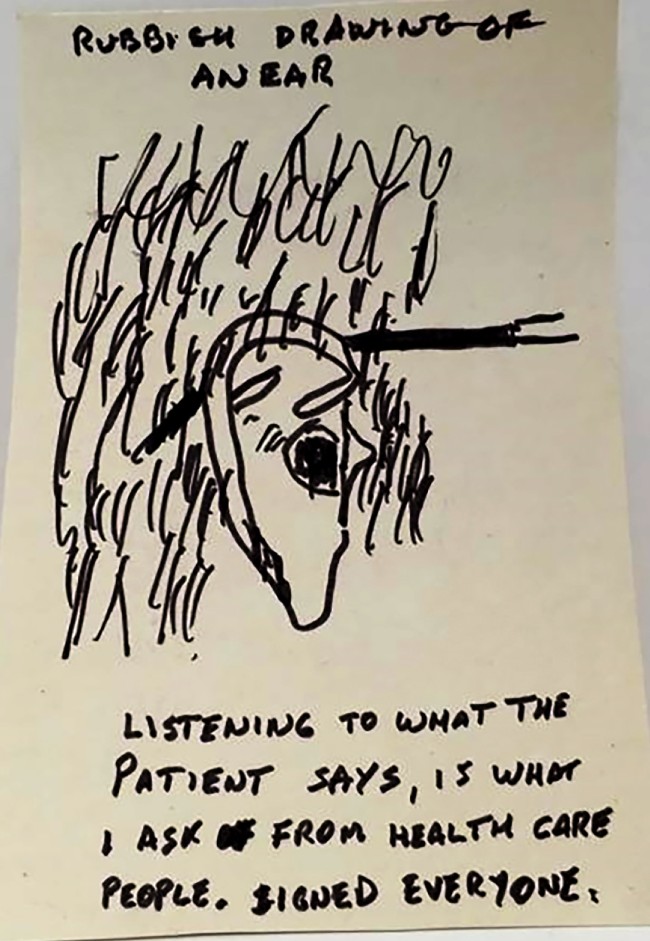

- Participants wished that the health care system was more person-centred. ‘Everyone is signposting and no one is providing any relational support.’ They want to be consulted on what approach or medication will be best for them. ‘Listening to what the patient says is what we ask for from the professionals.’ They wanted mental health services led by kindness and respect. ‘People in mental health crisis are deemed not to know their own mind.’

- For those experiencing mental health crises, accessing emergency mental health services can be extremely difficult and disempowering. 'I have capacity to ask questions but lots of my friends don't have that.'

3. Community strengths

Community organisations are playing a central and distinctive role in mitigating the impact of this crisis and in supporting people to look after and improve their health. Community support groups are experienced as accessible, reliable, non-discriminating and welcoming, and introduce and encourage healthy habits.

- Groups provide a safe, open space which supports vulnerability. ‘This is where the armour comes off and we can really talk’ (re. men’s group).

- Being a part of a group reduces social isolation, and helps people build resilience. ‘I didn’t have the confidence but once you’ve got some confidence you can do more.’

- Groups build connections across difference and increase community cohesion. ‘There’s no discrimination, all colours and creeds come together.’

- Groups can also maintain connections and identity within cultural communities , e.g. one user of the Dhek Bhal community group appreciated ‘keeping connection to Pakistan in the UK’.

- Groups provide a predictable, stable structure for the week which supports good mental health. ‘If I get up and think oh god another day I still come to the group.’ ‘It’s good to be connected, I like the text reminder. It’s good to be in someone’s thoughts.’

- Groups keep community voice at the heart of service development. ‘I’m not usually asked my opinion. It was good to be asked.’

‘This group is very important – what would happen to us without it? Everyone is really good at active listening, has compassion and empathy.’ (Phil, 72, Wellspring Settlement men’s group)

In this inner-city context, safe, green spaces are really important for exercise, relaxation, connection and learning.

- Flowers give people a lot of pleasure. ‘Colour cheers me up – my health is better when it’s colourful!’ • Walking gives a daily routine, a chance to see something new and connect with nature. ‘Even when it’s raining I still go.’

- Gardening is a very popular activity – both with others and alone. It’s a chance to get outside, meet people, get exercise, and connect with family and community heritage. ‘[Gardening] gets me out of the house. It’s rewarding because it’s hard work...I keep fit, meet other people at Gardening Club and get to make new friends.’

- Green spaces are important as a place to socialise, learn, relax and exercise – for example Netham Park, the Urban Park and the Avon river path. Safety access to toilets, benches, public transport and regular litter collection are key. ‘[I like] relaxing when I go to the park to look at the flowers.’

Participants had a strong vision of a colourful, clean, healthy neighbourhood, in which public services are well-resourced and accessible to all.

- Cheap, reliable, accessible public transport and no cars or dog mess on the pavement. • Safer accommodation, which is well-maintained, with better noise control and ventilation.

- Access to healthy, affordable food: fruit and vegetables, a halal butcher, good bread, a food club.

- Community hubs including a café, arts, culture and social activities, talks, a swimming pool, a football pitch, a community notice board, and a celebration space for communities and families.

- Women-only gym and swim sessions with creche facilities.

- Mental health crisis support in the community: ‘A place of safety with kind professionals who listen and sit with you in distress.’

Image: Dhek Bhal men's group

The research team

Sapna Boden, SEND Peer support worker for Mothers for Mothers

Hannah Charnock, Senior Lecturer in Modern British History, University of Bristol

Khrystyna Demchenko, translator and interpreter for Respond Crisis Translation with a law degree

Matshidiso Francis, tutor & mixed media artist who infuses language & art into making interactive journals & notepads

Jude Hutchen, Creative Research Co-ordinator for Wellspring Settlement and a visual artist based in ICE

Josie McLellan, Professor of History, University of Bristol

Aaruni Suresh, Research and Engagement co-ordinator at Caafi Health Bristol