The fight for financial inclusion: free access to cash must be guaranteed across the UK

The rise of digital payments has put cash and its infrastructure under pressure: first bank branches closed as online banking increased, and now ATMs are shutting down at record pace.

About the research

LINK’s initial policy response to protect ATMs through a financial inclusion subsidy has mitigated the damage done to communities to some extent. But more recent research calls for more radical change: for example, the Access to Cash Review emphasises the need to safeguard universal access to cash and call for the conversion of the UK’s wholesale cash infrastructure into a public utility to reduce costs and ensure its sustainability.

Whilst we agree in principle, we also recognise the need to explore the distribution of cash infrastructure across an urban area before working policies can be enacted. Cash remains important for many citizens who are excluded from mainstream financial products or distrust digital services, or those who rely on cash to manage their budgets.

Our research highlights how the unequal distribution of cash infrastructure affects those that are particularly dependent on it. A further reduction and/or concentration of cash infrastructures will increase the gap between those who need cash and those who have easy access to cash.

With policymakers in mind, we developed the Availability of Cash (AvCash) Index to provide an intuitive and comparative measure of access to cash infrastructure in UK neighbourhoods. It is based on publicly available data about the location of ATMs (both free and fee-charging), bank branches, Post Office branches, supermarkets that offer cashback and credit unions.

Our study focuses on the city of Bristol, but it has implications for other UK cities more generally. Data was collected in October 2018 in order to construct the index; however, data for ATMs was collected again in March 2019 in order to enable assessment of changes in infrastructure over time.

This policy report provides a summary of our findings and makes recommendations for policy. We encourage councils across the country to use our index to replicate the mapping exercise to inform policy-making.

Research Findings

• Residents’ ability to access cash is not evenly distributed across the city. Cash infrastructure (ATMs, banks, etc.) is concentrated in the city centre and a small number of areas of economic activity in particular local high streets.

• The provision of cash does not match local community needs. Communities most likely to depend on cash, in particular, those who are older or those living in deprived parts of the city and south of the River Avon, appear poorly served by current cash infrastructure.

• ATMs are changing from free to fee-charging, especially in deprived areas. 16 of the city’s ATMs changed from free to fee-charging between October 2018 and March 2019. Over two-thirds of these (11 of the 16 ATMs) were in deprived areas reliant on access to cash provided by private non-bank providers.

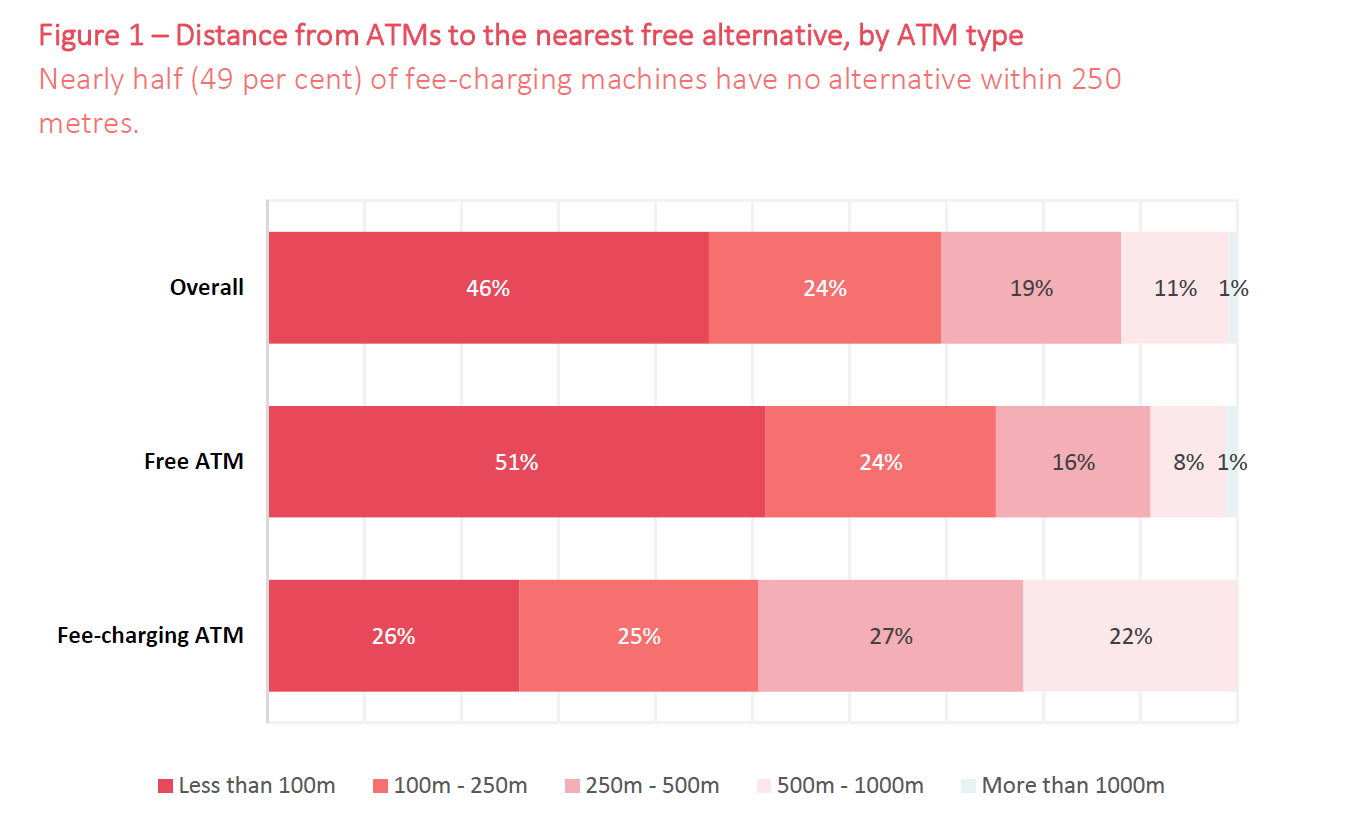

• Residents lack alternatives when ATMs close, malfunction or run out of cash. A quarter of ATMs in Bristol have no alternative within 250 metres; in the event of their closure or malfunction, residents potentially have to make a 500m or more roundtrip to the nearest alternative. As shown in Figure 1 (below), nearly half (49%) of fee-charging ATMs have no free alternative within 250m. This may have negative impacts for those with mobility issues and risks creating inner-city cash deserts.

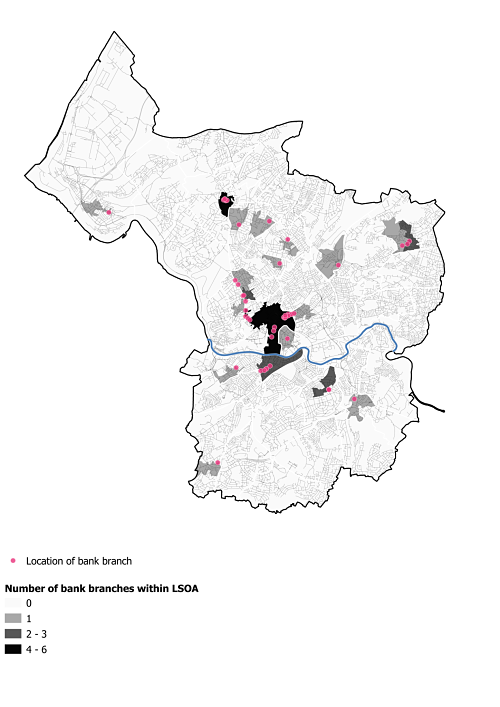

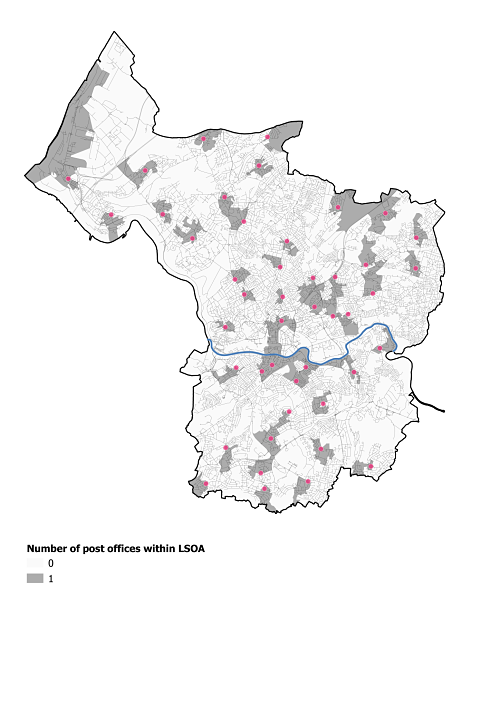

• Post Offices remain an important component of access to financial services. Post Offices are more evenly distributed than banks and ATMs (as highlighted by Maps 1 and 2) and represent a key infrastructure to safeguard the cash infrastructure in otherwise often under-served parts of Bristol.

Map 1 - Location of bank branches in Bristol

Maps 1 & 2 - Location of bank branches and Post Office branches across Bristol: Post Offices more evenly spread throughout the city.

Map 2 - Location of Post Office branches in Bristol

Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2019 Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2019.

At a glance: Bristol’s Cash Infrastructure as of October 2018

Figures suggest that Bristol has a well-developed cash infrastructure with 334 ATMs, 47 bank branches, 45 Post Offices and a credit union, as well as a selection of supermarkets known to offer cashback.

However, our research shows that the distribution of these infrastructures differs considerably across the city, as shown in Map 3. For example, areas south of the River Avon which tend to be more deprived and feature some of the worst ‘food deserts’ also appear to have less access to cash infrastructures: less than 20% of Bristol’s bank branches are located in areas south of the river, and many of these are in fact concentrated immediately to the south of the river.

Approximately a quarter of ATMs are fee-charging, and these tend to be in the southern and eastern parts of town, but not in the relatively well-off north-west areas of Clifton, Redland and Westbury, as shown in Map 4. This may hinder plans to enhance social, financial and economic inclusion in Bristol.

Charging for change: fee-charging ATMs on the rise in deprived communities

The rise of cashless payments has prompted a series of changes to the cash infrastructure. The most recent change was a reduction of the “interchange” fee from 25p to 23p per transaction to the operator.

Private non-bank providers’ reaction to these changes is particularly concerning for the prospect of ending financial exclusion. By turning free-to-use ATMs into fee-charging ones, Cardtronics, the UK’s largest private operator of ATMs, is hitting residents in deprived communities particularly hard. 11 of the 16 ATMs (two thirds) that switched to fee-charging are within areas that are among the 20% most deprived areas in the country.

Other private non-bank providers have announced that they will follow suit, which will put further strain on these communities. Issues arising from these changes to the cash infrastructure are not limited to Bristol but will affect cities and rural areas across the UK.

The Competition and Markets Authority has previously raised concerns about a potential increase in surcharge fees for consumers when examining Cardtronics’ proposed acquisition of DC Payments in 2017. It now appears that concerns were justified and that some key providers abuse their market position by introducing surcharges, which harms the UK consumer. As a result, any move towards reducing the cash infrastructure further must be subject to public scrutiny.

The idea that cash is entirely replaced by digital payments seems unlikely in the near future, so debate must consider cash payments alongside cashless ones, not as replaced by them.

Two-thirds of ATMs which changed from free to fee-charging between October 2018 and March 2019 were located in deprived areas.

Policy recommendations

Our detailed case study of Bristol’s cash infrastructure has clear implications for policymakers involved in the debate to protect the future of cash:

1. The mapping of cash infrastructure is essential to ensure that cash is available where it is needed; policymakers and advocates need to understand and recognise local differences to ensure policies are

sustainable and inclusive.

2. Commercial interests of private ATM operators should not come at a cost to the public. The widespread introduction of surcharge fees by private operators since 2018 should be investigated by a public inquiry to safeguard the consumer.

3. If the market fails to provide free access to cash for all communities then new policy measures including conversion of the ATM market into a public utility – a non-commercial, self-sustaining infrastructure owned by and operating for the taxpayer – should be considered.

4. LINK’s Financial Inclusion Programme should be extended to recognise other groups that rely on cash, such as the proportion of older people in an area or those with long-term health conditions. The

radius used to define protected ATMs should be reduced from 1km to 500m within urban areas.

5. Post Offices are pivotal in the fight for financial inclusion, as they currently offer the most evenly distributed infrastructure. Policymakers should consider how this resource could be best used for the public good, but in the meantime, any increased pressure on the Post Office infrastructure must be counterbalanced by increased resourcing.

Policy Report 52: June 2019

Financial inclusion: free access to cash must be guaranteed across the UK (PDF, 2,009kB)

Contact the Researchers

Dr Daniel Tischer

Lecturer in Political Economy and Organisation Studies

Mr Jamie Evans

Senior Research Associate

Ms Sara Davies

Senior Research Fellow

Further information

Full report: Mapping the availability of cash - a case study of Bristol's financial infrastructure

The Conversation blog: Older and poorer communities are left behind by the decline of cash

Authors

Daniel Tischer, Jamie Evans and Sara Davies (University of Bristol)