Seen but not heard: addressing the silent epidemic of child maltreatment in India

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 calls for a reduction in exposure or experience of any form of child abuse and neglect., particularly in children from lower- and middle income countries. The term ‘child maltreatment’ encompasses physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse, and physical and emotional neglect.

India has the largest population of children in the world (over 200 million) and data from UNICEF shows that Indian children are disadvantaged in their rights, access to education and healthcare, and are often exposed to physical labour and early marriages. A third of all child brides in the world are from India.

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012 is the only active child protection legislation in India specific to sexual abuse. However, its implementation has been poor, with delays in prosecutions due to the overburdened nature of courts and stigmatization of reporting child abuse.

This systematic review is the first of its kind, examining the evidence of all types of abuse and neglect in Indian children to determine how common child maltreatment is, and identify any differences by sex, population density, and legislation.

We identify specific risk factors and assess the effectiveness of the current legislation at tackling abuse and neglect.

Half of the girls interviewed from the largest study4 of over 12,000 children wished they were born as boys.

Policy recommendations

Government of India

• Current nationwide legislation is ineffective at countering specific cultural practices, such as child marriage, particularly in states with rural and tribal populations. Prioritise state-specific legislation.

• Prioritise policies and safeguards for those children most at risk: homeless or orphaned children, girls from rural or tribal regions and girls living in poverty or within urban slums.

• Create better social welfare frameworks for both home and school environments in which better safeguarding measures are put into place to identify vulnerable children or those who have had an experience of maltreatment.

• Implement and enforce the ban on corporal punishment across all Indian states.

Ministry of Women & Child Development

• Target policy and research funding to end corporal punishment as a normative cultural practice, such as focusing interventions on positive disciplining methods within homes and schools.

• Encourage behavioural change in parents/caregivers (positive parenting), helping to protect children from maltreatment at home.

• Prioritise measures that empower children with knowledge of their rights and builds core life skills (e.g. resilience and de-stigmatisation) in schools

• Raise awareness of all safe, accessible, and available channels to report abuse and neglect for children of all ages.

'Parents are the most common perpetrators of violence against girls'

– Rose-Clarke et al., 2019.6

Research findings

The systematic review1,2 consisted of evaluating 21 relevant studies published between 2005 and 2020 to determine the extent of child maltreatment, and any effects by sex, population density, population groups and POCSO implementation.

Twenty quantitative studies were state-specific, and one was nationwide. The studies included were based on self-report, child-report and assessment of child maltreatment by teachers or health professionals.

We excluded any study based on retrospective recall of maltreatment. Therefore, this review could be considered a snapshot of the time during which the studies were conducted.

This work builds on an earlier systematic review of child sexual abuse in India3 providing more detailed findings about all types of abuse and neglect over a 15 year period and the specific impacts of these on children by their sex, where they live, and housing and family status.

• We estimate that up to 74% of Indian children report physical abuse; up to 72% report emotional abuse and up to 69% report sexual abuse.

• Up to 71% of Indian children report overall neglect, up to 60% report emotional neglect and up to 58% report physical neglect.

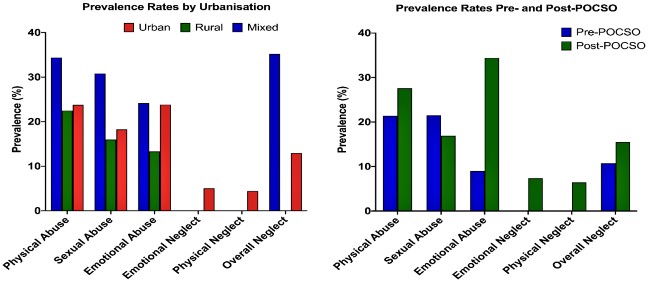

• Physical, sexual and emotional abuse and overall neglect is higher in rural and urban slum settings compared to urban settings.

• Children in socioeconomically advantaged households are four-times more vulnerable to physical violence compared with disadvantaged households. This is associated with academic achievements and expectations.

• Homeless children and orphans or runaways living in observation homes, particularly boys, are at increased risk of physical abuse.

• Girls who live in rural or tribal regions, urban slums, or socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, are at increased risk of child pregnancy and more likely to have restricted

access to food, health services and education.

• Within tribal populations, almost 70% of girls report a pregnancy during childhood (under the age of 18 years).

• In addition to being at higher risk of many types of abuse and neglect, the studies reveal a common theme for girls: the futility of reporting maltreatment, as girls were often ignored, judged as being ‘at fault’, and not provided with any protection from perpetrators.

’Grandparents sent this girl to the observation home and her brother stays with them as they are taking care of her brother because he is a boy and they have left her, to live in an observation home because she is a girl’

– Kacker et al., 2007.4

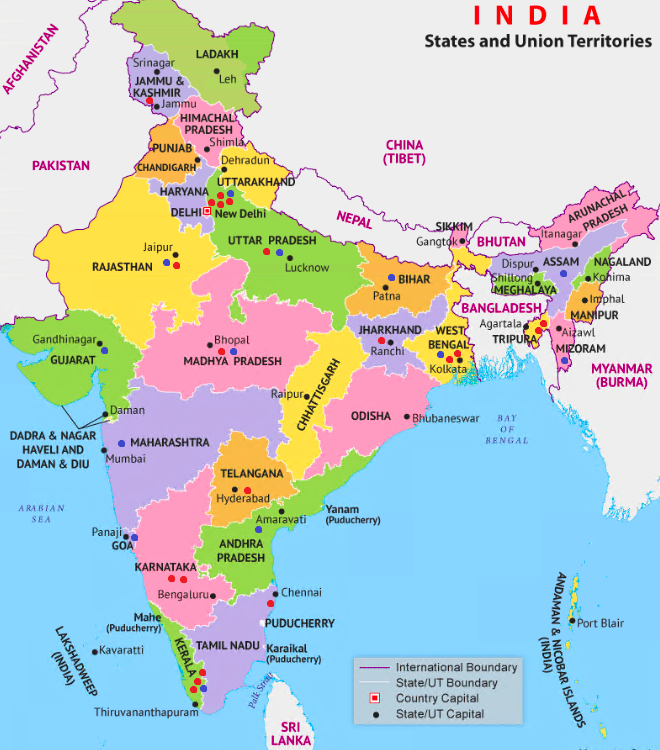

Key

Red: locations of individual-site studies

Blue: locations of the nationwide study by the Ministry of Women and Child Development

Taken from Figure 2. ‘Map of Indian states and union territories with red color showing the locations of studies selected for this systematic review and blue color showing the locations of Kacker’s nationwide study locations’, The prevalence of child maltreatment in India: a systematic review and narrative synthesis, Fernandes et al., 2021.

The effect of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012

Reported physical and emotional abuse and all types of neglect were higher after 2012 (post-POSCO implementation) but not for sexual abuse. However, our review found that

abuse and neglect often occur in tandem, rather than in isolation, though sexual abuse is often least reported of all types of child maltreatment.

This is attributed to the stigma associated with reporting child sexual abuse; the draconian punishment, the daunting procedures involved (in terms of time, resources and money) mean that parents and carers are less likely to pursue legal redress.

There is also a lack of multi-agency, collaborative, approaches to tackling child maltreatment (healthcare, legislation, social services, research).

We found emotional and physical neglect were only evaluated in studies conducted after 2012. The improved clarity around definitions of abuse and neglect and improved study design (e.g. robust and generalisable sample size) and methodologies may explain these findings.

’The fallout from eve-teasing include restrictions on a girl’s movements, ending her education, questioning her sexual purity and bringing forward her marriage’

– Beattie et al., 2019.5

Figure 2 Prevalence percentages of different forms of child maltreatmentmeans (%) by urbanisation

Prevalence percentages of different forms of child maltreatmentmeans (%) pre- and post POCSO

• Studies within mixed populations, i.e. including vulnerable children from both rural and urban slum settings, reported higher rates of physical, sexual and emotional abuse. Overall, neglect was also higher in mixed populations.

• Introducing child sexual abuse legislation in 2012 corresponds with an increase in overall reporting and evaluation of neglect and abuse.

Examples of good practice

ARPAN, a Mumbai based non-governmental organisation whose Personal Safety Education Programme aims to build core life skills in children between the ages of 5 and 16 years including interpersonal relationships, resilience, selfawareness and gender-awareness. The programme further provides counselling support for children and their families at schools following a disclosure of maltreatment. www.arpan.org.in

TULIR, a Chennai based non-governmental organisation that provides a personal safety education combined with therapeutic and socio-legal support to families and children

with experience of maltreatment. www.tulir.org

The Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation use a holistic approach to address pressing issues of children such as child labour, child trafficking, child marriage, child sexual abuse, education, health & nutrition and livelihood for parents. www.satyarthi.org.in

The Trafficking in Persons (Prevention, Care & Rehabilitation) Bill 2021 This bill aims to create a dedicated institutional mechanism at district, state and national level to prevent and counter trafficking practices, and to further dedicate resources to the protection and rehabilitation of victims. It also covers all aspects of human trafficking, such as sexual oppression, enslaved labour, slavery and organ smuggling.

'Over 80% of child domestic workers are girls under the age of 18 years, and over 80% of children working in tea shops and restaurants are boys under the age of 18 years. Almost 70% of child domestic workers have experienced physical abuse.'

– Kacker et al., 2007.4

Research next steps

The study team are mapping the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child maltreatment experiences in Indian children.

Further information

1. The prevalence of child sexual abuse and associated adverse childhood experiences in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. PROSPERO. www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=150403

2. Fernandes, GS, Fernandes, MK, Vaidya, N, DeSouza, PE, Holla, B, Sharma, E, Plotnikova, E, Geddes, R, Benegal, V., Choudhry, V., 2021. The prevalence of child maltreatment in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open. In press

3. Choudhry, V., Dayal, R., Pillai, D., Kalokhe, A. S., Beier, K. & Patel, V. 2018. Child sexual abuse in India: A systematic review. PLoS One, 13, e0205086. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205086

4. Kacker L, Vardan S, Kumar P, 2007. Study on Child Abuse: Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/study-child-abuse-india-2007

5. Beattie, T. S., Prakash, R., Mazzuca, A., Kelly, L., Javalkar, P., Raghavendra, T., Ramanaik, S., Collumbien, M., Moses, S., Heise, L., Isac, S. & Watts, C. 2019. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among 13-14 year old adolescent girls in North Karnataka, South India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 19, 48. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6355-z

6. Rose-Clarke, K., Pradhan, H., Rath, S., Rath, S., Samal, S., Gagrai, S., Nair, N., Tripathy, P. & Prost, A. 2019. Adolescent girls’ health, nutrition and wellbeing in rural eastern India: a descriptive, cross-sectional community-based study. BMC Public Health, 19, 673. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7053-1

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the study co-authors Miss Nilakshi Vaidya (NIMHANS, India), Dr Phillip De Souza (Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, United Kingdom), Dr Evgeniya Plotnikova (University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom), Professor Rosemary Geddes (University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom) and to Mrs Sarah Harding (University of Bristol).

Authors

Dr Gwen Fernandes (University of Bristol), Dr Megan Fernandes (Norwich and Norfolk University Hospital), United Kingdom Dr Vikas Choudhry (International Planned Parenthood Federation), Professor Vivek Benegal (NIMHANS), India

Policy Report 66: Oct 2021

Addressing the silent epidemic of child maltreatment in India (PDF, 476kB)