This intriguing tale of espionage and subterfuge is revealed in an essay published today in The Times Literary Supplement, confirming a long-held suspicion among scholars that Marvell led a double life.

Dr Edward Holberton, Lecturer in English, discovered the new evidence in a copy of Mr. Smirke, one of Marvell’s prose satires, which contains several handwritten notes by Marvell himself.

“I was doing some research into Marvell’s diplomatic career and European contacts. A new database of early European books became available online, so I started searching it for terms connected with Marvell and his patrons,” said Dr Holberton, who specialises in Early Modern Literature in the Department of English.

“What came up straight away was a scan of a copy of Mr. Smirke from quite close to home – the Wellcome Library in London. I flicked through it to see if there was anything interesting and came across the manuscript notes.”

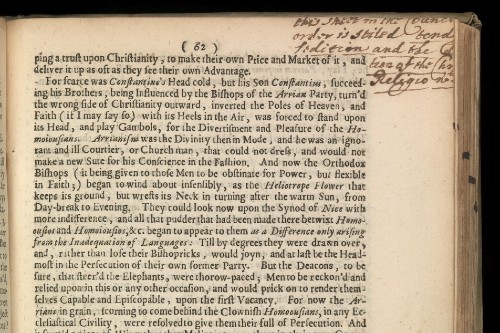

A particular annotation caught his eye, which read: “this sheet in the Counci[l]/ order is stiled tend[ing to]/ Sedition and the d[efma] / tion of the Chr[istian] / Religion.”

“It immediately rang a bell because I’d recently been editing an essay for the Oxford Handbook of Andrew Marvell, in which my co-authors, Martin Dzelzainis and Steph Coster, explain how Mr. Smirke had been censored because it had offended certain Bishops,” Dr Holberton said.

“The charge of ‘Sedition and the defamation of the Christian Religion’ was used on the arrest warrant for the pamphlet’s publisher. So it immediately struck me that whoever wrote that note, indicating the precise passage causing most offence to the Bishops, had very privileged information about the book’s publication and censorship. Then in dawned on me that I recognised the handwriting too,” he added.

“I went to the Wellcome Library a couple of days later to take a closer look and saw that it was clearly Marvell’s handwriting. But then I realised the cover and flyleaf of the book were very revealing too. There was a name and place on the first page - ‘Freeman … at the Hague’.”

This was also familiar, as Dr Holberton knew William Freeman was a leading member of a Dutch spy ring which had infiltrated English politics during the 1670s, and which smuggled pro-Dutch pamphlets into England to turn public opinion against the third Anglo-Dutch war. He had been linked to Marvell by historians before because there were rumours at the time that Marvell was connected to this spy ring, and that he even had a secret conference with William of Orange, who went on to become King William III of England, during the war.

“That rumour had always been treated by scholars with a degree of caution, but this looked like the smoking gun – evidence that Marvell sent Freeman a copy of his own political pamphlet, containing information about what was attracting the attention of the authorities in England at the time,” Dr Holberton explained.

It couldn’t be ruled out that an intermediary passed the pamphlet to Freeman without Marvell’s knowledge, but after discussions with another Marvell scholar, Nicholas von Maltzahn, a further connection dropped into place.

“Professor von Maltzahn pointed us to a letter he’d recently found, written by someone who only signed themselves ‘W.F.’ at the Hague, which had been intercepted by the government just after Marvell died in 1678. It discusses Marvell’s death, and calls him a ‘friend,’” Dr Holberton said.

“The handwriting matches Freeman’s on the cover of the book in the Wellcome library, and another example of Freeman’s handwriting which I found in the British Library. So this provides corroborating evidence that Marvell was indeed friends with Freeman.”

Today Marvell is better known for his metaphysical poetry, including the popular lyric ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ which argues: “Had we but World enough, and Time, / This coyness Lady were no crime.” During his life he was a respected politician, whose service in Parliament spanned 20 years.

He was held in such high regard that his monument, erected by his grateful constituency, bears an inscription lauding a man “who with an unutterable steadiness in the ways of Virtue [ ] became the ornament and example of his age…with such Wisdom, Dexterity, and Courage as becomes a true Patriot.”

Dr Holberton said: “This discovery sheds new light on Marvell’s political activities behind the scenes, which were tremendously risky at the time, and would have scandalised some of his fellow MPs. Next year marks the 400th anniversary of his birth and it’s fascinating that so many years on, we’re still uncovering new revelations about this influential, but enigmatic, literary and political figure.”