The early day motion (EDM) is a device used to publicise the views of individual Members of Parliament in the House of Commons. It allows MPs to express their opinion on a subject and to canvass support for it by inviting other members across all parties to add their signatures. Historically it was a motion put down by an MP calling for a debate on a particular subject. In recent years, however, the amount of government business and the increasing number of EDMs – now in excess of 2,000 a year – has meant that time is very rarely found for them to actually be debated. Nevertheless, public interest in EDMs is high and many attract press coverage, locally if not nationally, which is some-times their main purpose.

The topics addressed are hugely varied; anything from backbenchers seeking to accelerate or otherwise change Government policy, to those offering congratulations to a particular football club. Other EDMs relate to purely local issues, for instance, criticising the decision to close a post office or hospital. Only about six or seven EDMs each session attract over 200 signatures and the vast majority have considerably less than that, but whatever the subject, the key point about EDMs is that they are ‘unwhipped’. On most issues, MPs are forced by party whips to vote according to the party line. With EDMs, however, there is no party pressure put on individual MPs to sign (or not sign) one. It is therefore thought that an EDM gives a fair indication of what an individual MP really believes. As a consequence, Bailey and Nason considered that the signing of these motions would allow them to gauge whether political parties showed cohesiveness among their members. In other words, do MPs fundamentally agree with each other or, when expressing personal opinions, do they agree with members of opposing parties? They were also able to use the cohesion of EDM signatories to identify issues which cause political parties to unite or divide in opinion. The idea is that if things were going well for a party, MPs are cohesive – they all agree with each other and stick together – but if things are going badly for a party, they start disagreeing and have different opinions, so factions appear.

On most issues, MPs are forced by party whips to vote according to the party line

Using a variety of statistical techniques, Bailey and Nason were able to plot the cohesiveness of the three main parties during the period following the General Election in May 2005 when Labour won for a third term, but with a greatly reduced majority. The number of Labour seats was down from 413 to 356; furthermore, Labour’s share of the vote declined to 35 per cent, the lowest level in history to form a government with a majority. But the Tories, expected to make large gains, fared little better, causing Michael Howard, then leader of the Conservatives, to announce that he would retire from front-line politics. The results were interpreted by the UK media as an indicator of a breakdown in trust in the Government, and in the Prime Minister, Tony Blair, in particular.

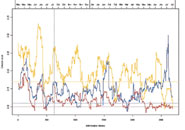

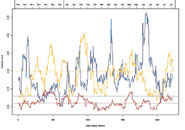

Unsurprisingly, the period following the election is marked by all three parties showing a considerable level of fluctuation in their cohesiveness, as if in some disarray (Graph 1). But after the summer break (dashed vertical line in June), things settle down and become more cohesive in each party, although overall, the cohesion of the Liberal Democrats is more variable than the others, due to there being far fewer MPs in the party, making the cohesion level more sensitive to differences in opinion.

Although Michael Howard resigned as Tory party leader after the election, he did not step down immediately. The leadership campaign lasted all of November and continued into December, with David Cameron finally emerging as leader on 6 December 2005. This is reflected in the trend in cohesion of the Conservative party which slumps in November and then rises, continuing an overall upward trend right through to the end of January. But then a further low can be seen during late March. The new leader was starting to show the direction in which the party was heading and a controversial education bill was narrowly passed, but only with Conservative support.

Following a disappointing General Election result, the leadership came under a lot of pressure

During the session, the Liberal Democrats’ cohesion level dramatically rises and falls. Following what many considered to be a disappointing General Election result, despite gaining seats, the leadership came under a lot of pressure. Activists felt the party had not taken advantage of a weakening government and oppos-ition and criticised the leader, Charles Kennedy, for his policies and election campaign. It was also known within the party that he was battling with alcoholism. After a period of intense pressure by high-profile party members, Charles Kennedy admitted having a problem and resigned as party leader on 9 January 2006. However, following the leadership election, Sir Menzies Cambell’s Liberal Democrats did not achieve the cohesion levels seen during 2005.

The Labour party generally exhibits lower cohesion than the other main parties and even after the summer break, there appears to be no significant change. Cohesion levels are at a level which suggests that MPs regularly disagree with other members of the party. One period of interest is that of March 2006. As with the Conservatives at this time, the cohesion of the party dropped. The education bill which was passed during this time split the Labour party, with mass rebellion from the Labour backbenches.

There is a lot of other information that can be gained from looking at this kind of data: does your MP really agree with party principles, or are they secretly more in tune one of the other parties? What are the issues that are causing your party trouble and strife? What is the overall mood of the party at any one point in time – just before an important vote, for example – and could the cohesion of the major parties be predicted? These are fascinating questions that other politicians, journalists and the general public might well be interested in having answers to.

Dan Bailey & Guy Nason / Department of Mathematics