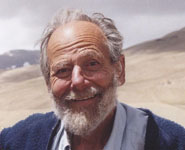

Like all older colleagues in the University who knew him, I learnt of Henry Osmaston's death with great sadness but also unforgettable memories. He died on 27 June 2006 at his home in the Lake District at the age of 83. Since he may now be less well known to some in the department (apart from the photo of him crossing a Himalayan river on a yak which hangs in the old University Road building), I thought a personal recollection might be in order.

He came to Bristol to a lectureship in the department in 1964 and retired as Senior Lecturer in 1986. So much for the bare record. But the 22 Bristol years were in some ways only a small part of Henry's long and distinguished life. He once told me his very earliest memory was of riding on an elephant! Born in the Himalayan foothills at Dehra Dun in India in 1922, his family had deep roots in colonial administration through the Indian Forest Service. Back in England he went to Eton (where he excelled at shooting) and then Worcester College, Oxford, where he began by reading

Chemistry but switched to his greater love (and continued a long family tradition), Forestry. World War II shortened all degrees and Henry left Oxford in 1943 for four years in the army (where he rose to the rank of Major), much of it spent in Egypt. His first posting in the colonial forestry service was to East Africa, and he developed the key forest management plans as Regional Forest Officer for Eastern Uganda, writing the definitive work on Ugandan vegetation and the first edition of his memorable guide to the Rwenzori Mountains ('Mountains of the Moon'). Anna found time from raising their four children (Amiel, Janet, Nigel and Charlotte) to write a wonderfully moving account of life in Uganda as a forester's wife in her poignant 'Uganda before Amin'. They formed a wonderful lifelong partnership.

Independence, Colonel Amin's accession, and the impending expulsion of all expatriate staff meant a new life had to be found. Henry returned to Oxford to write an outstanding DPhil on the palynology of some Rwenzori sediments, a thesis so highly commended by his external examiner – Sir Harry Godwin – that Peel at Bristol and Steers at Cambridge raced to appoint him. Bristol won.

I'll leave Keith Crabtree, Peter Smart and colleagues who worked closely with him on the joint Science degrees with Biology and Geology to fill in the Bristol details. He developed with Keith a quarter-century of Spring field excursions based in the Pollensa region in north-east Mallorca, and together they published a valuable a field guide to the Quaternary physiography of the island. Henry had huge energy and an idiosyncratic style of teaching because he found everything so fascinating, straying way beyond any dull disciplinary boundaries. I shall remember with pleasure long treks with him on local Quantock field days or away in the Ternelles valley in Mallorca where he opened up wholly new questions for speculation and research. Leaping unclothed into a cold tarn and inviting students to follow was all part of the 'Henry' tradition. So too were digging up shells (ordnance, not molluscs) at Sand Bay as evidence of recent sediment accumulation. As I said at his retirement: ‘No one of my colleagues is more likely to get you into a scrape; no one whom would you prefer to have with you in a tight corner; no one better at getting you safely out!’ Students will fondly recall the haymaking sessions after exams at his dairy farm in Regil and the many kindnesses of both he and Anna, not least the memorable (and occasionally explosive) Geography Society bonfire parties at the farm each November.

Retirement from the Department, selling the Regil farm, and the move to the Lake District was the start of a new and even more active life. They saw his continuing work on the Ladakh Valley in the eastern Himalayas with John Crook come to fruition in several major papers and volumes. Further visits to the Himalayas, Ethiopia, Uganda, Indonesia, were all fitted in, even though Henry was sometimes twice the age of other members of the party. Memoirs by early family members on India were saved from the archives, edited and handsomely published, a major CUP book on 'Tropical Glaciers' with Georg Kaiser written, and a second heavily revised edition of his classic 'Guide to the Rwenzori' completed. There were also papers on subjects as diverse as Lakeland tarns to weathering on Cambridge gravestones.

The last phone call I had from Henry was typical: it came just after midnight (Henry had no sense of time) and the crisp, unmistakeable voice said 'Peter. I need your advice on measuring the variability of angular direction measurements on ...' I referred him to Mardia's treatise and went back to bed.

Alpinist, forester, geographer, dairy farmer, indefatigable researcher, riveting – if sometimes eccentric – teacher. Perhaps we shall not see Henry's like again in the more uniform and less mirthful university world of this new century. I treasure an unforgettable memory of him as a free spirit who disregarded deep crevasses, restrictive University rules, and heavily-armed Indian border guards with a whimsical even-handedness. If I'm right in believing that learning isn't taught, it's caught, then Henry's restless spirit of inquiry, commitment and enthusiasm, caught a whole generation of geography students at Bristol.

Requiescat in pace.

Peter Haggett

Chew Magna

August 2006