Domestic Abuse: awareness and action needed on chemical control

This research explored the use of prescribed and non-prescribed medication (including vaccines) and other substances as part of coercively controlling domestic abuse.

Background/ context

In the criminal justice response to intimate partner violence and abuse (IPVA), there has long been an emphasis on physical violence as domestic abuse-related offences with police officers still largely responding to individual ‘incidents’ of IPVA (HMIC 2015). Yet perpetrators use many other coercive or controlling behaviours that undermine the self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-worth of victims-survivors over time. But these are not always obvious to witnesses, police officers, doctors, lawyers, judges, juries, nor by the victim-survivor themselves. Accounts from victim-survivors often reveal how it is these non-physical aspects of abuse that have the greatest impact and are more difficult to deal with.

Prosecutions of coercive control (Serious Crime Act 2015) in England and Wales remain even fewer than for domestic abuse crimes in general. Only 4% of the 33,954 offences of coercive control recorded by the police in 2020-2021 resulted in prosecution. There is concern that that the coercive control offence is still not being used to its full potential as criminal justice and other professionals are still missing key opportunities to identify patterned abuse.

While the current definition of coercive control covers many behaviours this is in no way exhaustive, and perpetrators may change the forms of abuse they use over time and within different contexts.

About the research

This research explored the use of prescribed and non-prescribed medication (including vaccines) and other substances as part of coercively controlling domestic abuse.

Forming the basis of this report the qualitative research on chemical control in IPVA involved three key elements: 1) re-analysis of six victim-survivor interviews from the Justice, Inequality and Gender Based Violence project; 2) an online victim-survivor survey resulting in 27 detailed responses and four individual online interviews; 3) an online focus group and interview with nine IPVA sector professionals. This report draws on the testimonies of those 37 IPVA victims-survivors plus nine professionals who work with victims-survivors.

The study formed part of a larger research project, funded by Oak Foundation, which aimed to deepen understanding of the nature, measurement and impact of coercive control. The Oak project included several strands of work including the use of faith and animal/pet abuse as strategies of coercive controlling domestic abuse.

This policy report demonstrates the need for increased awareness and understanding of the changing tactics used within coercive controlling domestic abuse.

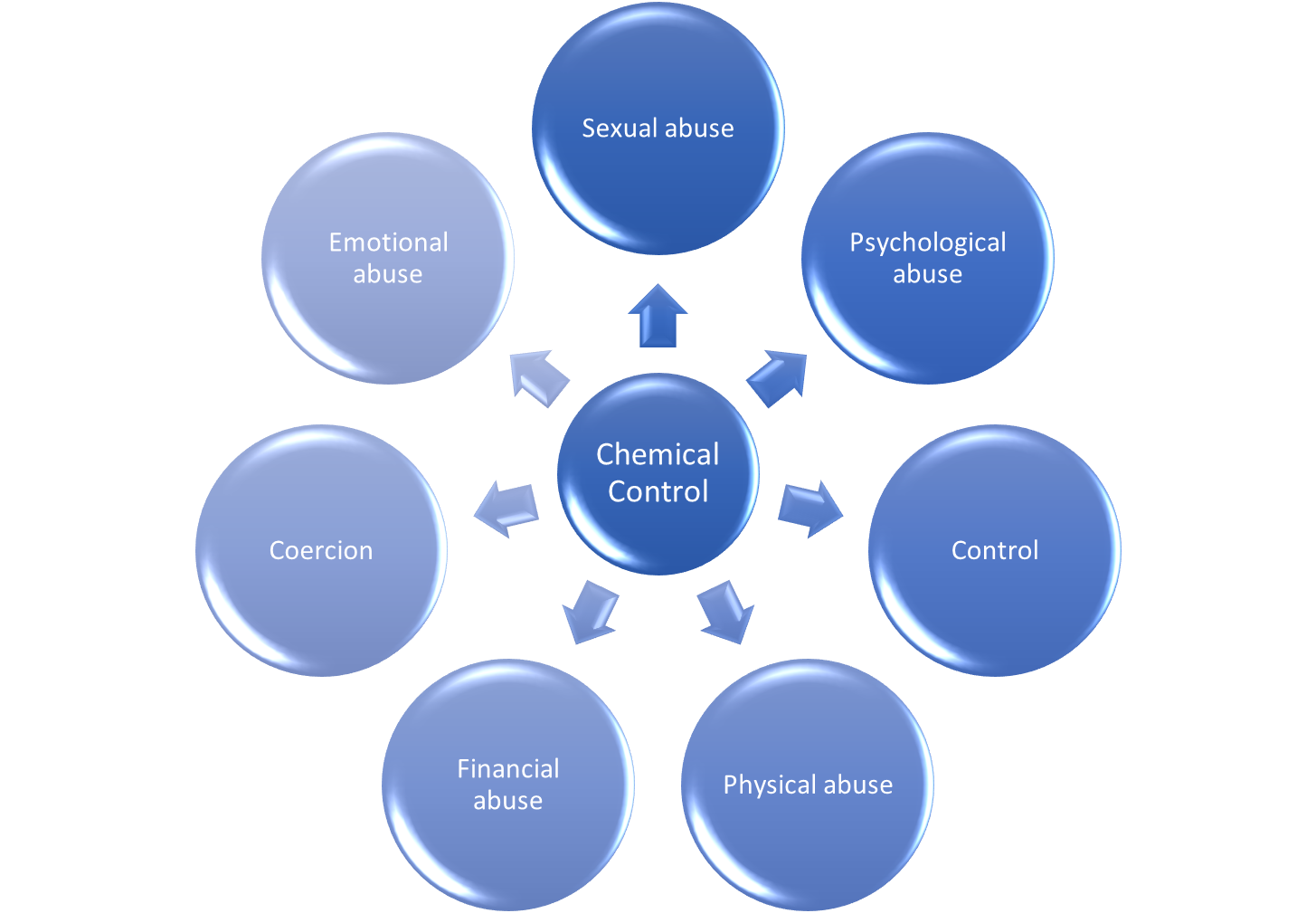

We focus on ‘chemical control’ which we define as the diverse, non-consenting use of prescribed and non-prescribed medication (including vaccines), and/or other substances by domestic abuse perpetrators to coerce or control victims-survivors.

Research findings

Perpetrators use chemical control to regulate, isolate and control the victim-survivor.

This reduces or erodes the victim-survivor's right to health, physical and mental integrity. Chemical control can exacerbate any existing illnesses or conditions a victim-survivor may have. But it also has the potential to cause illness or longer-lasting health conditions.

There is a need for improved awareness about how perpetrators 'weaponise' prescribed (and non-prescribed) medication, sometimes in combination with other substances, and the serious harm this poses to victims-survivors (and/or their children).

Perpetrators use chemical control as part of a pattern of abuse.

Tactics, such as disrupting or withholding the victim-survivor’s medication, can be either indirect and covert, or direct and overt. For example,

- Psychological abuse

Where the perpetrator convinces the victim-survivor that they are mentally unwell when they are not, or to take medication they do not need.

[he] started to hide the tablets, from day one. When I asked where the tablets where he would pretend I was going mad by making out he hadn’t touched them…[I] found them in strange places…I recognise now that he didn’t want me to start feeling better as he could control me better in the state I was in without them.

my ex convinced me to go to the doctors as he convinced me I was off my head and that I needed medication and I ended up taking anti-depressants when the problem wasn’t with me.

- Emotional abuse:

where the perpetrator withholds medication (including vaccines) from the victim-survivor’s child(ren); or ‘spikes’ food / drinks to undermine the victim-survivor's mothering capability (e.g., to sabotage an on-going child custody case, post separation).

I [was referred] to Children’s Services because in his mission to prove that there was nothing wrong with our daughter he decided to stop her medication and she ended up on steroids because her [condition] deteriorated… it should never have gone to court, even the judges have said that [but] Social Services believed in the stereotypical mother trying to stop contact with father when I reported him…I’ve had something like 36 apologies from Social Services for their failings.

- Financial abuse:

Where the perpetrator takes advantage of the victim-survivor’s need for medication for their own personal gain e.g.,

[he] would steal and sell my medication to finance his drug addiction [or] wait for my medication to take effect and [then] steal my money. He would harass me for money and/or my medication, sometimes for up to 10 hours straight until I gave him what he demanded.

- Sexual abuse:

Where the perpetrator withholds or administers medication /substances to facilitate sexual abuse e.g.,

I would be coerced to take the drugs and drink and have group sex. My husband liked to watch his friend having sex with me and drugs were an integral part of how this came about.

- Physical abuse:

Where the perpetrator sedates, pacifies or ensures the victim-survivor is completely dependent on them e.g.,

my pain levels became so high I was regularly hospitalised or bed-ridden, making me feel desperately isolated and unable to cope with daily life leaving me feeling suicidal.

Evidence suggests children can also be victims of perpetrators’ chemical control strategies.

- Perpetrators also (mis)use medication, to discredit victims-survivors as mothers. This often has an underlying threat of sabotaging the victim-survivor's child custody case (Callaghan et al 2018; Katz 2016).

Many victims-survivors may not recognise the tactics of chemical control whilst still in an abusive relationship.

- Although problematic, it is often difficult to detect or articulate because it can blend with normalised expectations of male and female behaviour. Receiving specialist support for the abuse experienced can help victims-survivors to recognise these perpetrator tactics as an intentional means to control them.

There are serious implications of chemical control for the health of victims-survivors.

- Besides the immediate pain or injury, there are longer-term physical and mental health implications of:

a) victim-survivor's not taking their medication at either the right time, frequency or dosage. This could lead to worsening disease, hospitalisation or even death.

b) victim-survivors' taking inappropriate or unnecessary medication. This can lead to longer-term issues, such as addiction, amongst victims-survivors.

- Using chemical control means that perpetrators do not necessarily need to use physical violence to coerce and control the victim-survivor. As such, perpetrators are less likely to attract the attention of the authorities. It is important to recognise chemical control as another tactic of coercive control when responding to domestic abuse.

It is important to recognise chemical control as another tactic of coercive control when responding to domestic abuse.

Policy recommendations

To effectively respond to domestic abuse, the tactics and related impacts of chemical control must be included within all domestic abuse awareness raising and training that is delivered to statutory and non-statutory agencies.

Training for professionals / practitioners:

- Practitioners such as community health workers, midwives and gerontological nurses must receive training regarding the tactics of chemical control, and the harmful impacts it can have on the physical and mental health of victims-survivors (and/or their children).

- Primary care practitioners including GPs and pharmacists, should be supported to recognise potential red flags e.g., where a patient is either under or over requesting prescriptions for their medication and not responding to treatment as expected.

- Professionals within Social Services and the Criminal Justice System (police / CPS / judges) need to be supported to recognise the potential for chemical control to be used by perpetrators to discredit victim-survivors in child custody cases post-separation, as part of an on-going pattern of abuse which undermines and restricts the liberty of the victim-survivor (and /or their children).

- Training for all professionals should also address the fact that it is extremely difficult for many victims-survivors to discuss this type of abuse. Even where the abuse may be relevant to alleged offending, disclosures may be limited initially, and survivors must be given the space and opportunity to expand upon any abuse they mention (Williams et al 2022).

- Specialist domestic abuse services/ professionals may also benefit from further training to help them support service users to recognise and disclose chemical control as part of the abuse. This could involve reviewing assessment questions so support services can more confidently respond to and mitigate the devastating impact of chemical control on victims-survivor’s (and/or their children’s) lives.

Awareness raising

-

Public awareness-raising campaigns are a central and long-established tool in the prevention of domestic abuse. The UK Government should help to raise wider awareness about the specific tactics of chemical control within any public information campaigns around coercive control and domestic abuse, to convey that chemical control is both a public health and human rights issue and show the benefits of eliminating it.

Further information

For more detail of the findings see:

Walker, S-J., Hester, M., and McCarthy, E. (2023) The Use of Chemical Control within Coercive Controlling Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse. Violence Against Women

Authors

Sarah-Jane Walker, Prof. Marianne Hester (University of Bristol), Elizabeth McCarthy (Women’s Aid Federation of England)

Policy report 87: Walker et al Domestic abuse and chemical control

Contact the researcher

Prof. Marianne Hester: marianne.hester@bristol.ac.uk

Centre for Gender and Violence Research | School for Policy Studies | University of Bristol, Priory Road, Bristol, BS8 1TZ