A breakthrough has been made by a team of scientists, led by Professor Stephen Hayden from the University of Bristol, in understanding how high temperature superconductors work. Their results, announced today in Nature (3 June, 2004), suggest they have found the ‘binding glue’ that allows superconductivity to happen.

High temperature superconductors are ceramic materials that can conduct electricity across huge distances without losing any energy. They are relatively cheap to make and have enormous potential in many areas of technology, but there is still controversy over what actually causes the superconductivity.

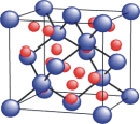

The structure of superconductors consists of many layers of atoms stacked on top of each other. Electrons easily move along the different layers, but rarely across them. Superconductivity occurs when electrons in the metal atoms pair up to form so-called “Cooper pairs”. They do this when there is an attraction or ‘glue’ that can hold them together. Formation of these Cooper pairs results in superconductivity – but what holds the pairs together?

Professor Hayden said: ‘Our results suggest that the glue may be due to the very weak magnetism of the electrons in the copper atoms of the superconductor. Thus the Cooper pairs are bound together by a sort of magnetic glue.’

The team from the University of Bristol (UK) and Oak Ridge National Laboratory (US), observed evidence of what might be the binding glue using MAPS, the latest spectrometer at the ISIS facility, CCLRC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire (UK).

This discovery will enhance our fundamental understanding of superconductivity. It is currently used in applications such as satellite and mobile phone transmission, and has enormous potential in a wide range of other technologies.