If asked to describe the smugglers of former centuries, most people would conjure up an image of cloaked men unloading brandy casks in isolated coves at the dark of the moon. But in an award-winning piece of research, for which he won the Economic History Society’s TS Ashton Prize, Dr Evan Jones of the Department of Historical Studies has employed accounting procedures similar to those used in modern fraud investigations to examine ‘white-ruff ’ crime in Tudor Bristol. Through techniques more commonly used against money launderers and drug racketeers, he has been able to reconstruct a widespread and profitable smuggling operation that was conducted by the commercial elite of 16th-century Bristol.

When surviving account books of the period are examined and compared to official records of trade such as customs books, it becomes apparent that Bristol’s merchants avoided paying taxes on a number of key exports. Most of the smuggling involved ‘prohibited’ wares – goods that the Crown banned from export. Prominent among these wares were foodstuffs such as grain, butter, salt beef and livestock. While the smuggling of such goods may seem relatively innocuous to modern eyes, it was considered a serious crime in Tudor England, given that food price rises could quickly lead to hunger and rioting. Another commodity on which the Crown imposed export bans was the guns manufactured in the Forest of Dean. In this case, the Crown’s main concern was that the weapons might end up in the hands of enemy powers. Unfortunately for the Crown, however, Bristol’s merchants were more concerned with their own pockets than the interests of the State. Unwilling to forgo the profits achievable on these lucrative trades, or pay for the export licences that could be obtained as ‘favours’ from royal officials, the merchants turned instead to smuggling.

For men like these, smuggling was not just a sideline

The research on Bristol’s records reveals that the city’s merchants were able to get away with large-scale smuggling because Bristol’s political and judicial bodies were dominated by the merchant-smugglers themselves. Those involved in this illicit business included some of Bristol's most famous merchants, such as Nicholas Thorne who established Bristol Grammar School, and John Smythe who created the Ashton Court estate. Indeed, of the 15 merchants now known to have been involved in the trade, no less than 10 served as sheriffs, mayors or MPs of the city. For men like these, smuggling was not just a sideline – it could account for up to a half of their total export trade and almost all their export profits. The merchants used their powers to subvert royal officials, prevent the seizure of their smuggling vessels and persecute those who informed on them. In a very real sense, Bristol was a city of smugglers.

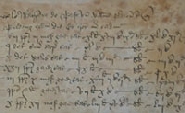

Nevertheless, despite the power of these men, if an informer made an official complaint about an illicit cargo, the customs officials had to take action. But even when this happened, the customs officers could aid the merchant by warning them of the planned search and assisting them afterwards if they were forced to seize the vessel. An excellent example of this is provided in a letter sent in August 1558 by William Tyndale to his brother Robert, warning him to depart with William’s illegal shipment of grain before it was seized:

I have had much talk with the Customer and Controller, who be honest men but yet (being informed) must needs do what they would not willingly. And therefore I pray God send time for that pinnace that she may depart, otherwise I fear me the officers must needs come aboard and for their own discharge do harm.

In the event, Robert did not get away in time and the ship, the Margaret of Elmore, was seized with 40 quarters of undeclared wheat. Despite this, the customs searcher, William Harvest, valued the ship at only £10 and, although an Act of 1554 stated that vessels carrying illicit goods should also be confiscated, Robert was able to redeem the ship by making an official payment of £2 2s 4d and an unofficial payment of £3 to Harvest. The true worth of the ship is revealed in William Tyndale's probate inventory (1558), which values the Margaret at £133 13s 4d, suggesting that Harvest's valuation of £10 was more than a little 'conservative'.

To encourage informers to pass on information about smuggling, the Crown offered them a 50 per cent share in any illicit goods that were seized. While this seems a generous offer, Bristol's merchant class were well placed to persecute informers. For example, in 1541 a man called Tegge Plowman reported that a Bristol merchant, Edward Pryn, was illegally exporting grain. Shortly afterwards, however, Plowman was provoked into a quarrel, which resulted in half the Town Council, including Pryn and the Mayor, coming armed to arrest him. As punishment for the 'affray', Plowman was put in the town pillory, where he was subjected to a humiliating and very public punishment. Pryn's capture for smuggling, on the other hand, appears to have had no adverse effect on his commercial or political career. He was made sheriff of the city in 1549 and became the first Master of the Society of Merchant Venturers – a body that remains influential in Bristol to this day.

Apart from revealing a murky aspect of Bristol’s past, the research demonstrates that it is possible to investigate smuggling operations in a more sophisticated way than has previously been possible. Before now, historians have always assumed that smugglers would not have kept records, or that they would have destroyed any records they did keep, but this was not necessarily the case. Moreover, since private commercial records were not considered valid evidence in prosecutions of smugglers until the 19th century, there was little reason why merchants would not have recorded their activities in their ordinary ledgers. Dr Jones’ work shows that official records tell only part of the story. Indeed, the thesis he is now developing in a new book, The Smuggler’s City, suggests that Bristol’s economic position, its pattern of development and the nature of its politics can only be understood if the role and importance of smuggling is understood. If this is the case for Bristol, it might also prove true for many other English ports.