The Elizabeth Blackwell Institute is honoured to bear the name of Elizabeth Blackwell in recognition of her outstanding contribution to healthcare both in the US and here in the UK. She was a pioneer, instrumental in many campaigns for reform, launching numerous health schemes, a tireless worker for health care, and a life-long opponent of slavery.

The opportunity to celebrate Dr Blackwell’s life of work prompts us to also reflect on the first Black female to earn a medical degree. Dr Rebecca Lee Crumpler graduated from New England Female Medical College, Boston in 1864, fifteen years after Dr Blackwell became the first woman to achieve a medical degree in the US. Yet, when we searched for an image of her for this blog, we realised that there are no validated photographs of her[i]. Instead, search engines populate erroneous illustrations of individuals who are identified as Dr Crumpler, but are in fact Mary Eliza Mahoney (first Black nurse in the US), Rebecca Cole (the second Black woman physician in the US), Elizabeth Blackwell, Eliza Grier (the first Black woman licensed to practice medicine in the state of Georgia), and other individuals. We will never be certain what Dr Crumpler looked like.

Recognition of Dr Crumpler’s life and work have been impacted by in prejudice. Her burial plot was unrecognised for more than 125 years, as people were walking on the grass where Dr Crumpler and her husband were buried at Fairview Cemetery in Boston. It was not until 2020 that the plot received recognition thanks to a group of Black historians and physicians who were determined to honour her life by installing a headstone at Dr Crumpler’s grave site[ii].

Dr Crumpler was raised by her aunt in Pennsylvania, who might have influenced little Rebecca’s career choice, as she spent much of her time caring for sick neighbours. When Rebecca was 21 she had moved to Massachusetts, where she worked as a nurse, and eight years later she was admitted to the New England Female Medical College to start her medical degree[iii].

Dr Crumpler graduated a year before the end of the Civil War, after which she worked for an agency created by the US Congress during Reconstruction to provide services to people who had been enslaved, but whom many White physicians refused to see. But, as Cindy Shmerler of the New York Times reports[iv], Dr Crumpler was continuously “ignored, slighted or rendered insignificant, even invisible.” She had a deep knowledge and the lived experience of Black communities and was aware that they were particularly vulnerable and at risk of ill health due to harsh living conditions and no access to preventive care. Yet, because of the intersecting social categories of gender and race, Dr Crumpler was blocked from directly admitting her patients to hospitals and providing services to them as a member of medical staff. She also struggled to get pharmacists to fill her prescriptions and was frequently racially harassed by administrators and fellow doctors.

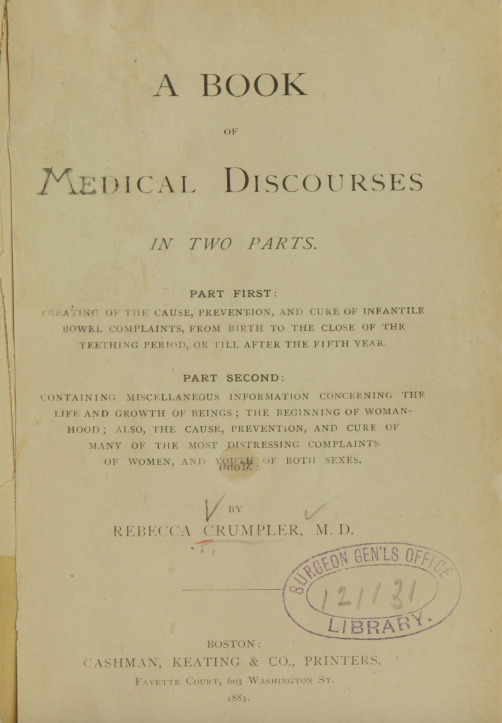

In 1883, her ‘Book of Medical Discourses’ was published covering the prevention and cure of childhood bowel complaints, and the life and growth of humans. It was dedicated to nurses and mothers, and it focused on maternal and paediatric medical care. This book is now seen as a precursor to prenatal “bibles” for pregnant women. Dr Crumpler was a pioneer for other Black female physicians who followed her steps, and we wish to amplify her achievements.

But Dr Crumpler is not the only Black female who had a profound impact on the medical professional community. Just over a 100 years ago, Henrietta Lacks was born.

Last year in October, a life-size bronze statue of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman, was unveiled at the University of Bristol by the artist, Helen Wilson Roe and members of Henrietta Lacks’ family to coincide with the 70th anniversary of Henrietta’s untimely death to a particularly aggressive form of cervical cancer.

Henrietta Lacks' cancer cells were taken for research experiments, at the time, without her or her family’s consent. Labelled ‘HeLa’, her cancer cells had the capacity to survive and reproduce in a laboratory, rendering them immortal and ideal for biological research[v]. Modern medicine would not be the same without Henrietta Lacks’s cells, as they have been used to reach key discoveries in many fields, including cancer, immunology and infectious diseases, and have been vital for advances such as the highly effective HPV vaccine, the polio vaccine, gene mapping, IVF treatment, and more recently vaccines against COVID-19. As Harvard’s Noel Jackson reports[vi] HeLa cells enabled vast amounts of research and more than 100,000 scientific PubMed publications and have led to many Nobel prizes.

But the story of Henrietta Lacks’ contribution to modern medicine brings a heart-breaking reminder of racism and injustice embedded in research and health-care systems. As reported in Nature, her cells were first collected with no consent in the period when few hospitals provided medical care to Black people. What is more, none of the organisations that benefitted provided any reimbursement to her family for the use of her cells. Injustices continued for decades after her death. Henrietta Lacks’ cells were used to develop medical treatments that were not available to all. All of these events have prompted a wider debate about HeLa cells and some have called for a reduction or an end to the use of HeLa cells in research, as the cells were taken without the Lacks’ knowledge or consent.

However, the Lacks’ family want HeLa cells to continue benefitting patients around the world. Henrietta’s grandson Alfred Lacks Carter, told Nature that the most significant thing to remember is that his grandmother’s cells have advanced cancer research, given that she was lost to cancer. They have also helped many people of all ethnicities, and although they were obtained in an unethical way, “they are doing good for the world,” Lacks Carter said.

An editorial in Nature in 2020, reported that scientists and the Lacks family have come together to create revised rules to govern the use of similar cell lines. Last October, WHO Director-General, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, bestowed Posthumous Award on the Late Henrietta Lacks, an act of historic recognition of her Life, her Legacy and her world-changing contributions to Medical Science. Through the Henrietta Lacks Initiative, the family is now educating future generations on the impact of HeLa cells while advancing health equity and social justice. They collaborate with WHO to eliminate cervical cancer worldwide, and increase COVID-19 vaccination confidence by educating, empowering and mobilising communities. (See hela100.org to find out more).

Henrietta has been described as ‘the mother of modern medicine’ and we are very proud that Henrietta’s statue has been placed on the University of Bristol’s campus outside Royal Fort House. This wonderful art work created by Bristol artist, Helen Wilson-Roe[viii], is the first public statue of a Black woman made by a Black woman to be permanently installed in the UK.

[i] https://drexel.edu/legacy-center/blog/overview/2013/june/is-that-dr-rebecca-lee-crumpler-misidentification-copyright-and-pesky-historical-details/

[ii] https://edition.pagesuite.com/popovers/dynamic_article_popover.aspx?artguid=214f9eaf-1c69-463e-ba89-14c9832d231b&appid=1165