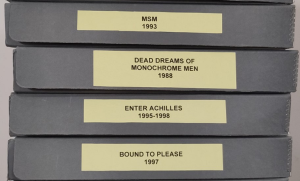

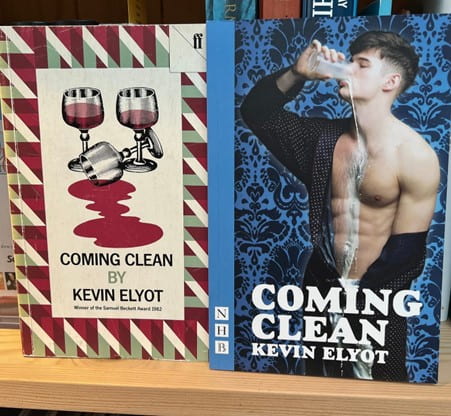

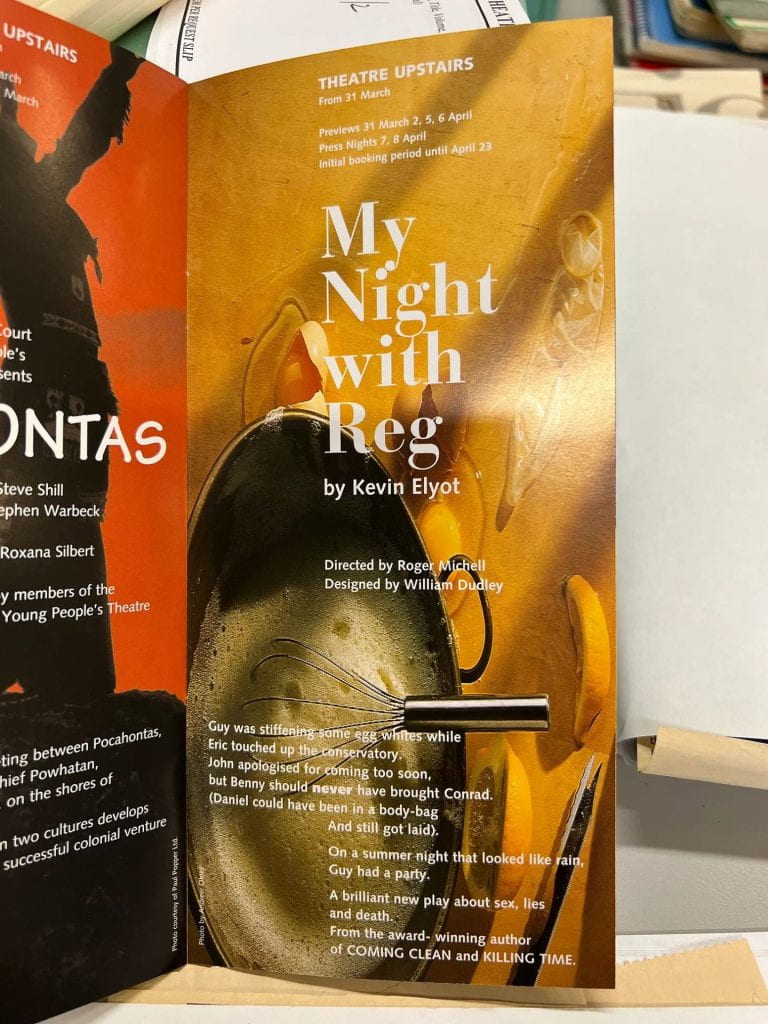

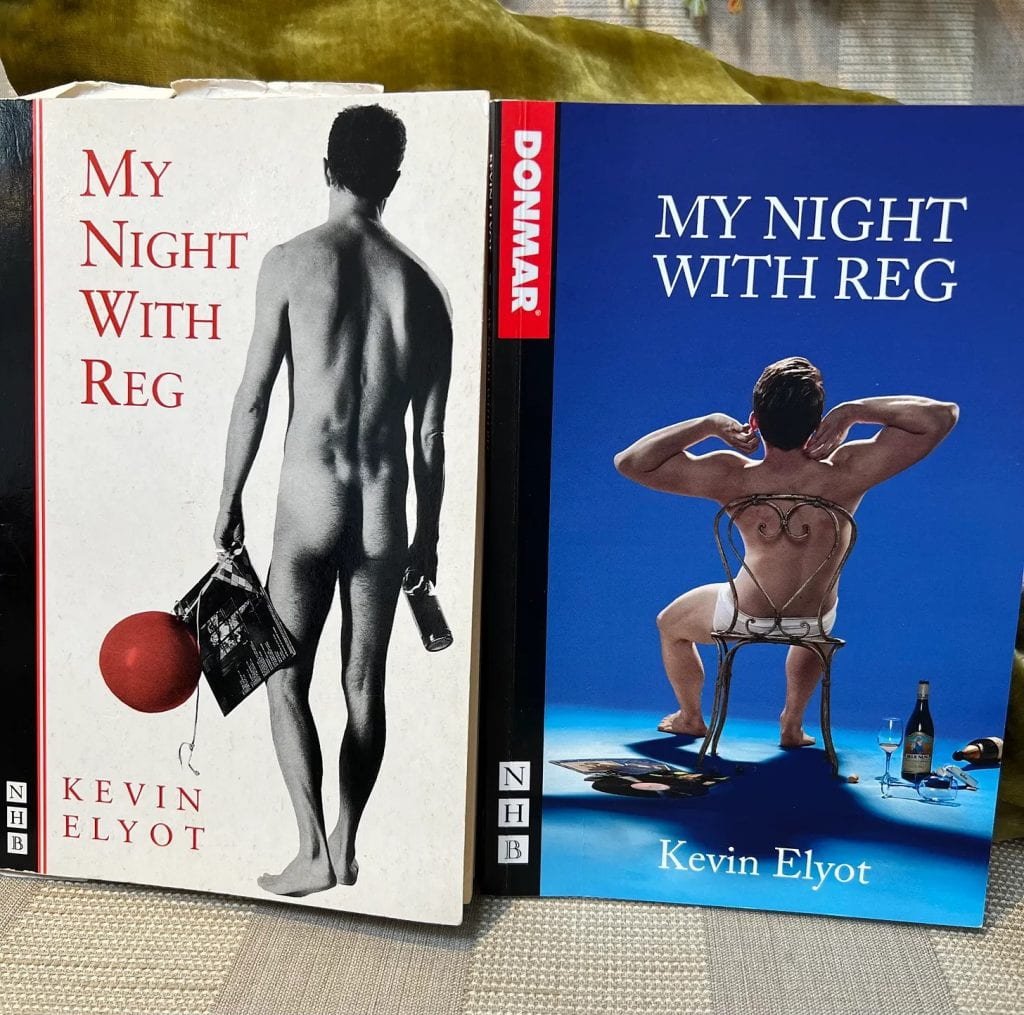

The Kevin Elyot Award is given annually to support a writer-in-residence at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection, where the archive of the playwright Kevin Elyot (1951-2014) is housed. 2024 is the tenth anniversary of Elyot’s death, and the thirtieth anniversary of My Night with Reg, his most famous play. In response to my time in the archive as the recipient of the 2023 Award, I have written a series of articles on Elyot’s six original plays. Here is the first, on his debut Coming Clean. (I have also written a general reflection on Elyot here.)

An actor writes a play

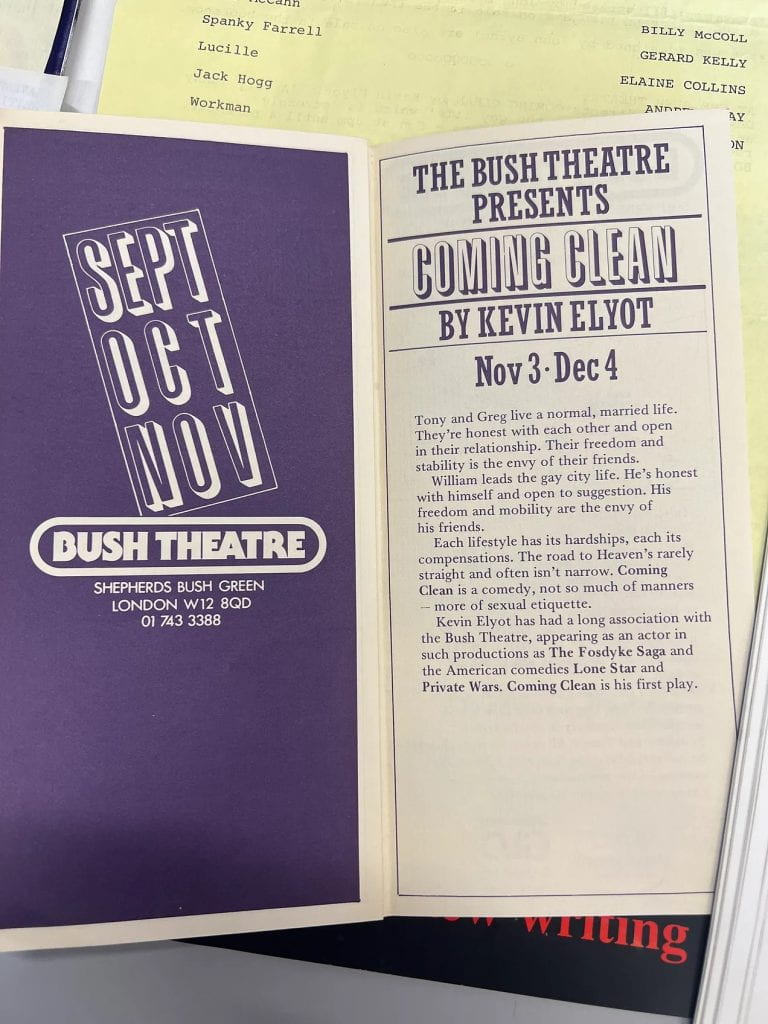

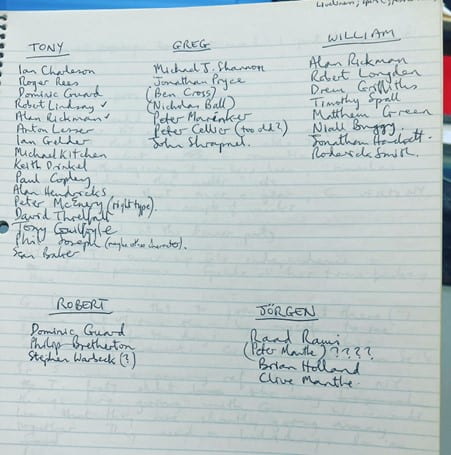

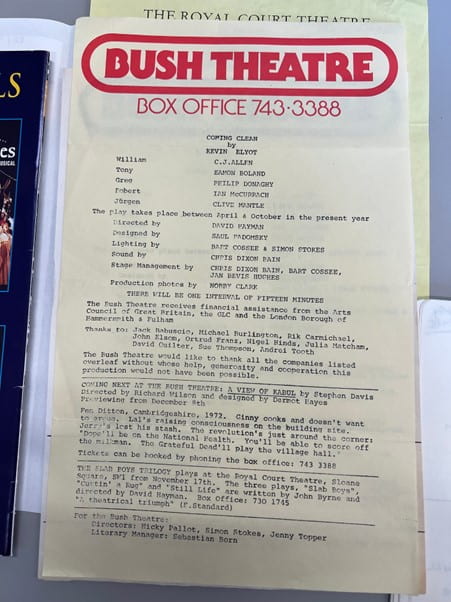

Kevin Elyot began his playwriting career at the Bush, London’s famous new-writing theatre, where as an actor he appeared in several productions between 1976 and 1984. Circa 1981, the Bush’s co-artistic director Simon Stokes suggested to Elyot that he write a play, which, Elyot told Plays and Players in March 1983, he did while

ill with hepatitis. I don’t know whether you’ve ever had it, but you just have to sit around until you get better. I had nothing much else to do, so I wrote the play.1

Entitled Cosy upon delivery, then Clean Living during its development at the Bush, this tale of infidelity in gay relationships premiered as Coming Clean on 3 November 1982.2 David Hayman’s production played to packed houses, though reviews were mixed: here polite, there homophobic. The New Statesman claimed that were the play’s all-male love triangle ‘translated into heterosexual terms,’ it would be ‘universally shrugged off as psychologically and theatrically humdrum.’ The Mail on Sunday prophesied that ‘in time, it will be recognised as the first mature play about homosexuality.’3

The text attracted the attention of the legendary play agent Peggy Ramsay, who subsequently represented Elyot for a short time, and it won the 1982 Samuel Beckett Award.4

At the heart of Coming Clean is a ‘happily married’ gay couple in North London, Tony and Greg. They have an ‘open’ relationship:

TONY: […] infidelity is a fact of life. We both enjoy the occasional one-night stand. We don’t do it all the time, and we’d never bring anyone back if the other one was here. Perhaps it’s not ideal. But I think it’s realistic. I’d much rather have that than be deceitful to one another – pretending we were faithful when we weren’t.5

This arrangement is tested when Tony engages a cleaner named Robert. Greg and Robert have an affair, and after Tony walks in on them having sex, Greg announces to Tony that he loves Robert – and Tony. For Tony, ‘the whole point’ of their arrangement ‘is that we shouldn’t have to lie to each other’; but for Greg, ‘[t]he whole point is that we should stick together! And if that means we have to lie to each other, then that’s fine by me!’6

The central question is encapsulated in one of Elyot’s notebooks, held in his archive at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection:

[…] theory of an open relationship + the practice of it – the two don’t mix + leads to destruction.7

Ultimately, Tony admits to Greg that Greg is the only man he wants, but Greg can’t abide anything so ‘domestic’:

GREG: […] I still love you. I still want us to be together. But I’m not suddenly going to ask you to lay out my pipe and slippers. And I doubt that Robert will suddenly disappear into thin air.8

In the poignant final scene we gather that Tony has been unable to accept being one of Greg’s two objects of love. He has a heart-to-heart with Jürgen, a German pick-up – but neither speaks much of the other’s language. As Schubert plays on the stereo, Jürgen, himself hurt by some relationship, stammers, ‘Und … now … no more love … never!’ ‘You can’t say that,’ Tony cries, ‘I can see why you should but … no, you can’t say that.’9

Elyot’s voice

At the opening, the audience hears something clichéd: the famous Adagio of Samuel Barber’s String Quartet. Before he learns of Greg’s affair with the cleaner, Tony confesses to his friend William that Greg has been distant. William tells Tony to prepare a ‘really romantic evening,’ and ‘when [Greg] walks in, have that piece of music playing – you know, the dreary piece, the one that you both call “our tune” … the Barbirolli …’ Tony corrects him: ‘Barber.’12

Lots of couples share an ‘our tune,’ and William’s inability to remember the composer, and his characterisation of the music as ‘dreary’, immediately destabilises Tony and Greg’s.

The next scene begins with Greg and the cleaner Robert having it off – while the Adagio plays on the stereo. ‘Our tune’ has ironically – cruelly – become the soundtrack to an affair. To intensify Greg’s betrayal – sex and music – and to foreshadow that Tony and Greg’s open relationship cannot survive it, Elyot then reveals that Greg hates the Barber: ‘Would you mind if I turned this off? It’s like a fucking funeral.’13

After Tony and Greg argue the play’s central question in the wake of Tony’s discovery of the affair, Tony goes to the record collection to find something to play. When he sees that the Barber he wants is already on the turntable, there is a moment between the doomed couple. ‘Obviously, a popular choice,’ Tony says, ruefully.14

‘Our tune’ is dead.

Elyot’s notebooks reveal just how dramaturgically calculated all this is; how alive he was, even at the beginning of his writing career, to the power of subtext and allusion. Tony’s sentimental attachment to, and Greg’s rejection of, the Barber symbolise the opposing positions in the play’s argument. Contrasting Barber with the more radical and tragic figure of Schubert (whose music accompanies the final scene), Elyot wrote, ‘Barber is a musical reactionary, which fits Tony’s position (esp. as Barber was gay).’ The play’s ‘archetypal clash’ between ‘a socialist theory’ (represented by Greg, advocate of the open relationship) and a ‘reactionary lifestyle’ (represented by Tony, who cannot curb a desire for monogamy – a conservatism ‘EMBODIED IN HIRING A CLEANER FOR FUCK’S SAKE!!!)’ is reflected by the couple’s attitudes towards the Barber – by the ways the play interrogates the Barber as a cliché.15

It’s not the point that an audience should be conscious of such layering, but that the layering should work upon the audience’s unconscious, and deepen the somewhat shallow scenario. Elyot started as he meant to go on: such attention to detail, such allusions to musical and literary worlds beyond the world of play, are hallmarks of his writing.

Critical homophobia

Irving Wardle in The Times is worth quoting at length:

My test for homosexual plots is to see how they respond to heterosexual conversion. You can get three possible results: either the story will ring as true with women as with men; or it will be so specifically homosexual as to resist the change; or it may be unmasked as a parasitic copy of a heterosexual model.

So far as plotting is concerned, Coming Clean belongs to the third category; and I resent the force of the Gay Lib movement in getting stage space for plays that would stand no chance whatever if they featured triangles of debs and stockbrokers. Mr Elyot’s chart of ‘contemporary sexual mores’ takes you straight back to the world of commercially packaged sex comedy.17

Putting aside the sexism (no such thing as gay women in Wardle’s World, or gay stockbrokers, or female stockbrokers), as well as the telling choice of the word ‘conversion,’ Wardle of course put the play into the wrong category of his three. So far as plotting and everything else about Coming Clean are concerned, it belongs to his second category, because this play by a gay playwright about gay men explores the ‘conflict between theory and practice’ in open relationships as a gay conflict.18 It doesn’t mean the play isn’t universal: Elyot recognised that his theme is explored in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which, he wrote, ‘beautifully expresses the argument between ideal + actual, love + lust, the appeal of marriage v. the appeal of promiscuity.’19

But to put Coming Clean into his second category would have required Wardle to remove heterosexual spectacles, to do something we now take for granted: give a queer play a queer reading. He would have had to interrogate the cruising in the play (‘I just popped into the cottage for a tea-time quickie’) as gay.20 The music (Barber, Village People, Voggue) as gay. The queer-bashing (William is assaulted by ‘a bit of rough trade’) as gay.21 The sex (sodomy, blow jobs, rimming) as gay. William’s hilariously camp diction (‘Loose? I expected to find half of London up there [a man’s arse]. Do you want a jammy doughnut?’) as gay.22 Tony’s inability to reconcile his feelings with Greg’s world-view, and his characterisation of parts of the gay scene as ‘disgusting, unamusing, unentertaining, mindless, sexist, repressive drivel’, as politically charged gay disputes.23

Too hard for Wardle. Homophobia was easier.24

In fact, Elyot resisted the term ‘gay writer’. He told the journalist David Benedict at the time of The Day I Stood Still, ‘Of course I am a writer, and I am gay, but that kind of characterisation is a way of belittling the writing.’25 To Time Out, he said he wanted The Day I Stood Still to be judged as a play, not a gay play:

I think that sort of categorisation is very restricting. I don’t want to be compared to other gay writers, I want to be compared to other writers. I’ve noticed recently that the ‘gay writer’ nomenclature has tended to disappear – I know this sounds terribly politically incorrect – but I find that a bit of a relief, not because I’m not proud of being gay, but I think one is taken more seriously.26

Perhaps reviews like Wardle’s still smarted – even if, in 1983, he had fought back rather magnificently:

If he had thought it through it would have been an even more radical play if it had been about a heterosexual couple – because I’ve not seen a straight play where you have the partners sleeping around, then a third person coming along and the husband saying, well, not only am I going to continue sleeping around but you’ve also got to accept that I’m in love with this other woman and I also want to continue my marriage with you. What you get in straight plays is a third person breaking it up and then an ensuing fidelity with the new person, which is not what my play was about.27

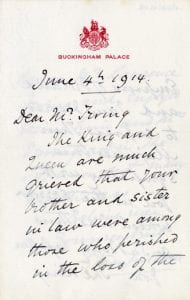

A remarkable letter

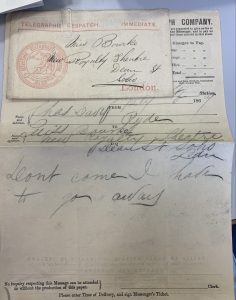

In his Introduction to a collection of his plays, Elyot says that Peggy Ramsay, the famous play agent who read countless first plays over her career, was in tears at the Bush when she saw the final scene between Tony and Jürgen: ‘That’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen.’28

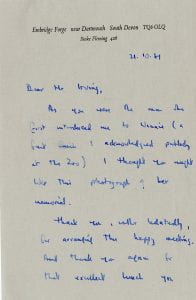

What Elyot does not mention is a remarkable letter Ramsay wrote to him before she visited the Bush but after she’d read the play, in which she acknowledged his competence as a playwright, and the sexual frankness in his writing, but reproached him for a ‘holding back over exactly how people behave in these circumstances.’ She saw in Elyot a restraint, a cowardice, and in a handwritten addendum, eulogised Thomas Mann for his preparedness, presumably in Death in Venice,

to plunge into the abyss of filth & deviation, & the result was a kind of purity, since NOTHING IS DISGUSTING – the only disgusting thing is NOT to face the truth; right down to the lowest depths! This takes great courage, & you need to explore it.

Ramsay did not think Coming Clean a good play, did not think it art. Her letter, entirely encouraging, was a cri de cœur to the first-time playwright: ‘if you write another Play about homosexuality I beg you to make it deeper.’29

How to survive a plague

the handling and resolution of the crisis are expressed in terms which are uniquely gay. Debs and stockbrokers, on or off stage do not, indeed cannot, talk, act, think or see their lives as Greg and Tony do.

But Baker says that ‘ultimately [Coming Clean] is slight, lacks weight.’ Like Ramsay, he encourages the first-time playwright ‘to extend his undoubted ability and vision next time.’30

In the 255th edition of Gay News, dated 9 December 1982, there is an article titled ‘DISEASE FEARS HIT UK: Prepare for shocks in ’83’:

BRITISH GAY MEN had better prepare themselves for some major shocks in the months ahead. They will be under a double-edged attack from both disease and media coverage if recent American experience is repeated here.31

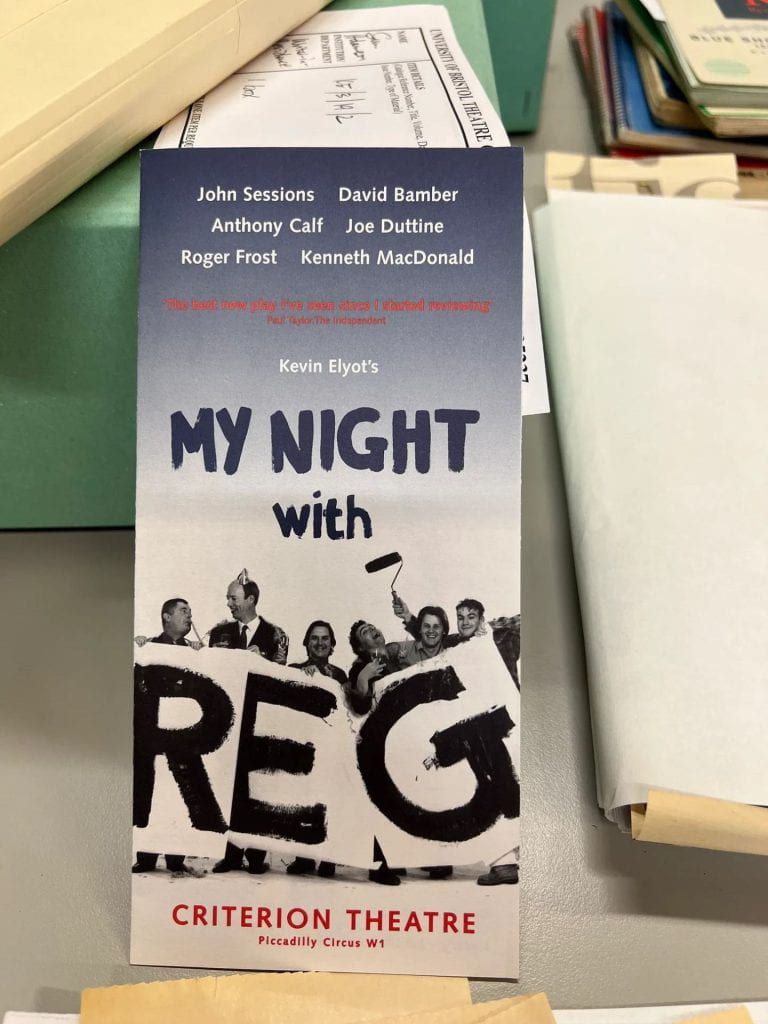

It would take Elyot twelve years to write his second play My Night with Reg. It was finally produced in 1994, and though it shares many qualities with Coming Clean, it is a much more sophisticated play. In it, Elyot faces the truth and extends his vision, just as Ramsay and Gay News had hoped he would. But its subject is tragic: the lives and deaths of gay men during the age of Aids.

In 2004, Elyot looked back on the final scene of Coming Clean and said, ‘it has an elegiac quality – in retrospect, almost a sense of foreboding.’32 There were no revivals during the worst of the Aids years, or during Elyot’s lifetime, though at a 1997 gala to celebrate 25 years of the Bush (at which I was present) a scene was performed by the original cast. ‘I was pleased to discover that it still packs a punch,’ Elyot said in 1998, even if it felt to him ‘a sort of period piece’.33

In 2017, the play was successfully revived at the King’s Head Theatre, London, and as I write this, there is a revival at Turbine Theatre, London. Of the King’s Head revival, Exeunt Magazine found the play’s central question – ‘Can you ever really have your cake and fuck it (and the rest of the bakery)’ – ‘as current now as it was 35 years ago.’34

An autobiographical first play that announced a major talent – a play about gay sex and infidelity that premiered before everything changed for gay men – had survived both critical homophobia and Aids, and its pre-Aids question had become pertinent again.

1 Kevin Elyot, Introduction to Four Plays (London: Nick Hern Books, 2004), pp. ix-x; Elyot to Christopher Edwards, ‘More Promising Playwrights’, Plays and Players, March 1983, pp. 23-4 (p. 24), University of Bristol Theatre Collection (UBTC), KE/3/5/15.

2 UBTC, KE/3/5/3.

3 London Theatre Record, November 4-17 1982, pp. 615-16, UBTC, KE 3/5/6.

4 Elyot, Introduction to Four Plays, pp. ix-x; UBTC, KE/3/5/13.

5 Elyot, Coming Clean (London: Faber, 1984), pp. 37, 49.

6 Ibid, p. 58.

7 UBTC, KE/3/5/2, 3 of 5, p. 59.

8 Elyot, Coming Clean, p. 64.

9 Ibid, pp. 71-2.

10 Elyot to Edwards, p. 24.

11 Elyot to Sue Summers, ‘Day follows Night with Reg’, Daily Telegraph [n.d.: interview at the time of The Day I Stood Still, 1998], UBTC, KE/3/23/5.

12 Elyot, Coming Clean, p. 50.

13 Ibid, p. 52.

14 Ibid, p. 65.

15 UBTC, KE/3/5/2, 3 of 5, p. 59.

16 Elyot to Bob Workman, ‘Kevin Elyot Comes Clean’, Gay News, 255, 9-22 December 1982, pp. 38-9 (p. 39), UBTC, KE/3/5/6.

17 Irving Wardle, Times, 8 November 1982, [n.p.], UBTC, KE/3/5/6.

18 UBTC, KE/3/5/2, 2 of 5, p. 95.

19 Ibid, p. 95.

20 Elyot, Coming Clean, p. 39.

21 Ibid, p. 39.

22 Ibid, p. 13.

23 Ibid, p. 46.

24 Intriguingly, Wardle wrote in 1973 a play called The Houseboy with a scenario not dissimilar to Elyot’s; its television adaptation was broadcast a few months before Coming Clean’s premiere.

25 Elyot to David Benedict, ‘National debut? Time to put the record, er, straight’, Independent, 14 January 1998.

26 Elyot to Jane Edwardes, ‘Life after Reg’, Time Out [n.d.: interview at the time of The Day I Stood Still, 1988], UBTC, KE/3/23/5.

27 Elyot to Edwards, p. 24.

28 Elyot, Introduction to Four Plays, p. x.

29 Margaret Ramsay to Elyot, 17 November 1992, UBTC, KE/3/5/13. Sadly, this letter does not appear in Colin Chambers’s Peggy to her Playwrights: The Letters of Margaret Ramsay, Play Agent, a book I recommend.

30 Roger Baker, ‘Coming Clean’, Gay News, 254, 25 November – 8 December 1982, p. 29, UBTC, KE/3/5/6.

31 Bob Workman, ‘Disease Fears Hit UK: Prepare for shocks in ’83’, Gay News, 255, 9 December – 22 December 1982, p. 3, UBTC, KE/3/5/6.

32 Elyot, Introduction to Four Plays, p. x.

33 Elyot to Edwardes.

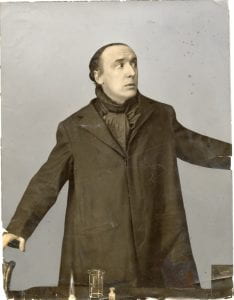

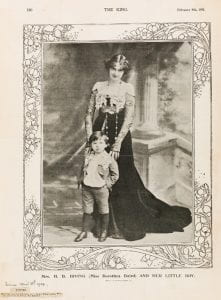

[Conceptual Design by Ralph Adron. Theatre Collection Reference: BTC71/1/6/1/4]

[Conceptual Design by Ralph Adron. Theatre Collection Reference: BTC71/1/6/1/4]