Education in the Maldives

- An Overview of the Country

- The Maldives Education system

- Current Developments, Priorities and Challenges in Education

- 16th UKFIET Conference on International Education and Development

- Links to some educational institutions in the Maldives

- References

An overview of the country

The Maldives is a series of small coral atolls located 370 miles southwest of the southern tip of India and 400 miles west of Sri Lanka, scattered north of the equator in the Indian Ocean. It stretches 510 miles north to south crossing the equator and 80 miles east to west. More than 99 per cent of the country is the sea. The islands stretch over 26 naturally occurring atolls, set up into nineteen administrative divisions (atolls), which at present are organised into seven Provinces under local governance structure. The low-lying 1,190 islands rise no more than 6 feet (1.8 meters) above sea level. Eighty per cent of the landmass is one meter or less above the sea level, making the country acutely vulnerable to changes in sea-level rise and other consequences of global warming. About 200 islands are inhabited, with a further 100 islands having resorts exclusively on them.

Archaeological findings reveal the islands were inhabited as early as 1500 BC by the sun-worshipping ‘Redins’ who may have been the first explorers of the islands (Heyerdahl, 1986). It is also believed that Tamil and Sinhalese people from southern India and Sri Lanka were the first settlers in the Maldives.

The Maldives remained an isolated and independent nation throughout its political history, except for a brief period of colonization by the Portuguese in 1558. Throughout its recorded history, the Maldives remained a monarchy. It first became a republic in 1952, which survived for seven months before reverting back to a monarchy. The country was under the British protectorate from 1887 until 1965. On November 11th, 1968, became a republic once again with President Ibrahim Nasir as Head of State and government. President Nasir’s tenure in office ended in 1978 succeeded by President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom who was head of state for six consecutive terms of five years from 1978 to 2008.

The Maldives is at the crossroads of three major transitions: a widespread movement in support of a full-fledged democracy, the economic emergence of the country as a middle-income nation and the natural phenomena of global warming and rising sea levels. Managing the convergence of these transitions is at the heart of development reality for the country. The Maldives shares the same economic characteristics of most other Small Island Developing States; scarcity of natural resources, small labour market and diseconomies of scale. The economy is critically dependent on a small number of sectors, with 30% of the GDP coming from tourism. The country has seen strong economic growth over the last two decades, mostly driven by the fast growth in the tourism sector. The dominance of tourism in the economy makes the country vulnerable to variations in the global economic and social conditions.

The Maldives is classified as a middle-income country with a per capita Gross National Income of US$ 6,530 in 2011 (World Bank, 2013), with a GDP growth of 7.5% % in 2011. The country ranked 104th in the human development index (HDI) for 2018. The Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 totally destroyed 14 inhabited islands and displaced more than 12,000 persons.

After independence in 1965, the Maldives joined the United Nations (UN) and became a member of numerous bodies like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). It became a member of the Commonwealth in 1982. In October 2016 the Maldives walked out as a member of the Commonwealth Countries alleging that the Commonwealth sought to interfere with the Maldivian politics. With the change in new government, the Maldives rejoined the commonwealth as its 54th member on the 1st of February 2020.

The population of the Maldives was 491,589 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2018), with just over one-third of the population being school-going age children. Of this population, a large proportion is foreign labourers who have migrated from neighbouring countries such as India and Bangladesh, representing an estimated 15.8% of the population in the Maldives. Further, one-third of the country’s population resides in the capital city Male’ (National Bureau of Statistics, 2018).

The high geographic dispersion of the population poses a challenge in the cost-effective provision and delivery of basic services of education and health raises issues of access to these services. The dispersed nature of the inhabited islands also presents challenges in applying for developmental programmes equitably. There are significant differences and disparities between the urban centre of Malé and the outlying rural island communities in access to services including education (Di Biase, 2017).

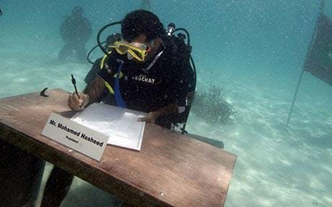

Politically, the country had been in turmoil since 2003, which had seen calls for democratic reform and more representative government. The formation of political parties was allowed in 2005. Basic civil liberties like freedom of speech and association were tolerated, if not altogether allowed. A special constitutional council drafted and passed a new constitution in August 2008, and the first-ever multi-party, multi-candidate presidential election was held in October 2008. Mohamed Nasheed was elected as the president of the new democracy and as Bonofer comments, ‘he inherited a government that was economically bankrupt and politically nascent which was prone to infighting within the government’ (Bonofer, 2010, p. 440). President Nasheed has been a champion at bringing the environmental vulnerabilities the Maldives is facing due to climate change to the forefront of the agenda for many developing countries via various platforms. He had communicated this matter at the United Nations and is famously known for the Underwater Cabinet Meeting he held in 2009. He was also featured in a documentary called ‘The Island President’, which received global attention for the environmental challenges we face.

The Maldives Education system

The Maldives’ education system is said to be influenced by a variety of factors, including religious-based Islamic education, informal schooling and Western traditions in formal schooling.

A brief history of the education system in the Maldives

These three systems of education have created the simultaneous operation of a formal education system in parallel to the informal education system, with informal education heavily impacting formal education. According to Mariya (2012) and Shiyama (2020) early-childhood-education (ECE) in the Maldives starts from the informal education system, where children from the age of two years are sent to Edhuruge to learn reading and writing in Dhivehi, Arabic script to recite the Quruan, and basic numeracy and religious prayers. The endpoint of this informal system of schooling is when the child completes reading the whole Quruan. The foundation of schooling that starts from Edhuruge has implications for both students’ learning styles (Gupta, 2018).

There is also a strong British influence in the Maldivian education system; one space of influence was their role in shaping the introduction of Western-style, English-medium schooling. With support from the British power in the region, the first Western-style, English-medium school was opened in Male’ in 1927, and was limited to boys only. In 1944, the establishment of a similar girls’ school in Male’ is considered the first formal step in the provision of gender-balance in education (Mariya, 2012). Once the Maldives got its independence, there were rapid changes to the education system, with support from various external aid agencies. In 1980, the Ministry of Education (MoE) started centralising the schooling system; thus, the first national primary school curriculum was introduced, formalizing English as the medium of instruction in all public primary schools (UNESCO-IBE, 2011). This curriculum was revised in 1984 whereby a national curriculum for middle school and primary school was introduced. For secondary schools, the General Certificate for Secondary Education (GCSE) subject-specific syllabi were to guide teaching. Three discrete curricula documents were used in formal schooling, structured on a 5-2-3-2 cycle (five years of primary schooling, two years at the middle school, three years of lower secondary school, and two years of higher secondary school (Mohamed & Ahmed, 1995).

The 1990s rapid development to the education system in the Maldives took place. With support from countries such as Japan, and global funding bodies such as the World Bank, United Nations, and the Asian Development Bank, schools were built in every inhabited island.

Tertiary education in the Maldives

During the 1970s and 1980s tertiary education was available to few students usually from a selected few families (Muna, 2014), today more and more students who complete secondary education seek opportunities to go into tertiary education. Even before the government of Maldives formally acknowledged the rising demand for the local provision of in-country tertiary education, beginning from the early 1970s, a number of post-secondary training institutes were established. The number of distinct and separate post-secondary institutions continued to grow in number today, reflecting the country’s growing need for specialist post-secondary and tertiary training to support the growing economic demand for specialist skills. The proliferation of these separate institutions further reflected that the rising demand for skills could not be met solely with overseas training and scholarships, as had been the case in the past. Within the 30 years beginning from 1970, postsecondary institutions were set up to provide education and training in areas of teacher education, travel and tourism, administration and management, accountancy, technology, maritime industry and most importantly community health services (Muna, 2014). The training institutes in these separate fields were set up under the respective line ministries to fulfil the training needs of that particular ministry. In 2001, these institutions were unified under the umbrella of the Maldives College of Higher

Education, which in 2011, was officially declared as the first university of the Maldives, (The Maldives National University (MNU) 2011; Muna, 2014). Currently, with The Islamic University of Maldives (IUM), there are two public universities in the Maldives, while there are seven private higher education institutions that operate as colleges.

The current school education system

Global forces of education development play a role in shaping the education system in the Maldives (Di Biase, 2019). For example, when UNESCO launched the Education for All and the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), the Maldives implemented them and duly reported on achieving universal access to primary education across the country in 2000 (Ministry of Education, 2008). Further, with local initiatives for basic education and literacy programmes that started in the 1980s and continued throughout the 1990s, the Maldives has reported a 98.94% literacy rate, which is impressive when compared to neighbouring countries (Shiyama, 2020).

In the last decade, the education system in the Maldives has undergone many changes. The biggest change was the introduction of an Outcomes-Based-Education (OBE) National Curriculum in 2015, as detailed below.

The New National Curriculum in the Maldives

To address the demands of a globalised world, in 2003, the MoE decided to revise its existing national curriculum (Shiyama, 2020). A new curriculum mapping school education from Kindergarten to grade 12 and emphasising skills and key competencies was formulated with consultations from numerous stakeholders. According to the Ministry of Education & Ministry of Higher Education (2019), the mission of the new curriculum is:

- To provide opportunities to all girls, boys, youth and adults, to acquire knowledge and skills, as well as nurture in them values and attitudes, to thrive and actively participate in nation building, and live as responsible global citizens in an interconnected world. (p. 14).

According to the National Institute of Education (NIE) (NIE, 2011), this curriculum provides schools and teachers with a thorough framework, starting from broad educational visions to assessments and accountability measures, mapping the whole school-learning experience seamlessly across all grades and Key Stages. Further:

- The key competencies provide the basis for lifelong learning and employability in a progressive and challenging world. Each key competency is built on a combination of cognitive and practical skills, knowledge, values, attitudes, dispositions, and other social and behavioural components. (p. 2).

The school academic year in the Maldives consists of two terms of 20 to 22 weeks each. Schools have class-specific weekly timetables allocating subject-specific teaching sessions or periods. The medium of instruction for this curriculum is English and for subjects such as Islam, Quruan and Divehi language are taught in Dhivehi. Currently, all teachers in the Maldives are required to hold at least a bachelor's degree in teaching. Further, in November 2020 the first Education Act in the Maldives was approved by the Parliament and this mandates teacher registration, within the next two years.

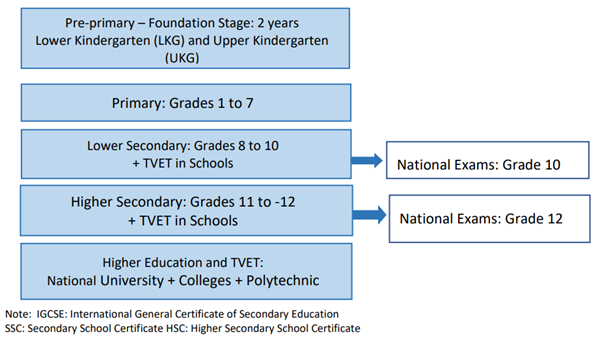

An important change that came to the schooling system with the introduction of the new curriculum was the introduction of the Key Stage system. According to NIE (2011), this restructuring was meant to provide more flexibility in teaching content across the Key Stages and to provide teachers with more flexibility in their pedagogies. The new system is shown in Figure 1 below. This system is similar to the Key Stage system in the UK.

Figure 1 - Current School education system in the Maldives.

Another recent change was aimed at universalising access to both primary and lower secondary education. In 2010, all the primary and secondary schools in the Maldives were restructured to offer grades 1 to 10. Currently, a majority of the 212 public schools teach grades 1 to 10 (Ministry of Education & Ministry of Higher Education, 2019) and all are fully implementing the new national curriculum. However, with this move of changing school structure, together with limited school size necessitated a two-session school system; 7am to 12:30pm for lower secondary grades (grades 6 to 10/12) and 12:45pm to 5:30pm for primary grades (grades 1 to 5). This two-session schooling system has extensive repercussions for the quality of school teaching and learning (Shafeeu, 2019).

In terms of class-size and gender ratio in primary schools, the average classroom size is 30 students, with an approximately equal number of boys and girls, with a reported teacher to student ratio of 9:1 in the capital Male’ (Ministry of Education & Ministry of Higher Education, 2019). However, this ratio varies in island schools where teacher attrition is problematic (Shafeeu, 2019), so class sizes may reach 40. In 2018, there were 2923 men and 6653 women working as teachers in public schools. Such numbers demonstrate the popularity of teaching as a female profession.

The common pedagogical approaches used in school education in the Maldives has been reported as examination-oriented, teacher-centric methods that are heavily content laden (Di Biase, 2017). However, with the advent of the new curriculum, there have been various attempts of introducing learner-centred, skill-oriented pedagogies, with varying level of success reported (Di Biase, 2019; Shiyama, 2020).

Current Developments, Priorities and Challenges in Education

In 2019, with aid from Global Partnership in Education (GPE) two important and timely documents in the Education sector in the Maldives were published. They are the Education Sector Plan (ESP) for 2019-2023 and Education Sector Analysis (ESA). The main areas of focus highlighted in these documents with regard to the future of the education sector are below:

- The context for the development of the education sector

- Cost and financing for equitable quality education services for all

- Access, enrolment, K-12 grades/Out of school children and youth

- The National Assessment of learning outcomes (NALO)

- Curriculum reform to improve learning (Multi-grade teaching, Technology in education, Inclusive education - The special educational needs (SEN) programme, Early childhood care and education, Teacher quality and school facilities)

- Technical vocational education and training, in and out of school

- Higher education

- Education and training contribution to the economic and social development of Maldives (external efficiency)

- Organisational aspects and evidence-based data for decision making

Challenges for Education due to COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has no doubt magnified the existing challenges to the education system in the Maldives. Currently, in recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the education system, the Ministry of Education has expressed that ‘most of the sector concerns and challenges to be addressed post COVID-19 are not new. In fact, they relate to a magnification, due to the scale of this crisis, of already existing disparities and inequities that have been within the school system for many years’ (Ministry of Education, 2020 p. 9).

Over 91,000 students were affected by the closing down of schools and 85 percent of the students physically could not attend school for almost all the academic year 2020. To mitigate the challenges that could rise from the long term closure of schools the measures taken by the Ministry of Education were, first in establishing a COVID-19 Education Response Team and developing a contingency plan aligned with the National Health Response Plan. Standard operating procedures (SOP) were issued to schools and an Education Response Plan (ERP)was initiated. Continuation of education was carried out through televised lessons and online platforms which were available to a limited number of students. As highlighted in the ERP the prolonged closure and discontinuation of education will lead to learning loss, increased dropouts and higher inequalities which could reverse the educational gains the system has experienced during the last decade. Research findings regarding these issues are concerning, as have been highlighted in the recent (2020) OCIES conference presentation by ESSRG members.

16th UKFIET Conference on International Education and Development

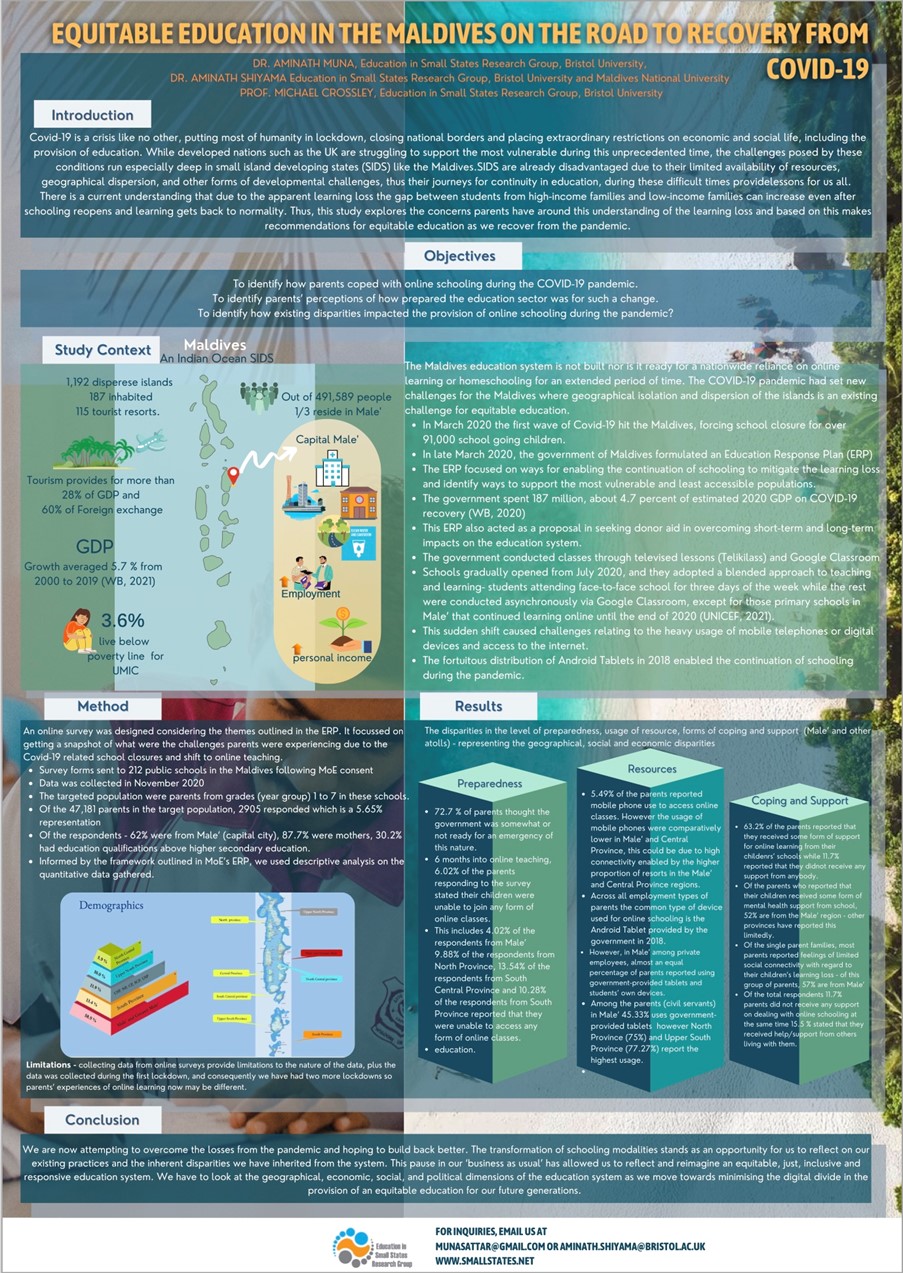

The members of Education and Small States research group (ESSRG) participated in the 16th UKFIET Conference on International Education and Development from 13-17th September 2021. The theme Building Back Better, Reimagining, reorienting, and redistributing education and training opened up the opportunity to the international education and development research community to reflect, redesign to build back better.

Our team members joined the conferenced in two different categories and the poster below was presented by Dr Aminath Muna, Dr Aminath Shiyama and Prof. Michael Crossley.

Links to some educational institutions in the Maldives

- The Maldives National University (https://mnu.edu.mv/)

- Islamic University of Maldives (https://www.ium.edu.mv/)

- Villa College Maldives (http://www.villacollege.edu.mv/)

- Ministry of Education, Maldives (https://www.moe.gov.mv/en/page)

- Ministry of Higher Education (https://mohe.gov.mv/)

- National Institute of Education (https://www.nie.edu.mv/)

References

Bonofer, J. A. (2010), The Challenges of Democracy in the Maldives, International Journal of South Asian Studies, A Biannual Journal of South Asian Studies, July to December 2010 (3) 2, pp. 433 – 450

Di Biase, R. (2017). Mediating global reforms locally: A study of the enabling conditions for promoting active learning in a Maldivian island school. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives,16(1), 8– 22.

Di Biase, R. (2019). Moving beyond the teacher-centred/learner-centred dichotomy: implementing a structured model of active learning in the Maldives. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(4), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1435261.

Gupta, A. (2018), How neoliberal globalization is shaping early childhood education policies in India, China, Singapore, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. Policy Futures in Education, 16(1), 11-28.

Heyerdahl, T., (1986), The Maldives Mystery. Bethesda, Maryland: Adler & Adler Publishers, Inc.

Mariya, M. (2012), ‘I don’t learn at school, so I take tuition’ An ethnographic study of classroom practices and private tuition settings in the Maldives. PhD thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North.

Ministry of Education, & Ministry of Higher Education., (2019), Maldives education sector plan: 2019-2023. Male’, Maldives.

Ministry of Education (2019). MALDIVES COVID-19 Accelerated Funding Application Form for Global Partnership in Education. Ministry of Education: Maldives.

Mohamed, A. M., & Ahmed, M. A. (1995), Maldives education policies, curriculum design and implementation at the level of upper primary and general secondary education. Paris, France.

Muna, A., (2014), Evolution and Development of Tertiary Education in the Maldives, EdD Thesis, University of Bristol.

National Bureau of Statistics, (2015), Maldives: Ministry of National Planning Housing and Infrastructure. http://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/population-and-households/ (accessed 12 December 2020).

National Bureau of Statistics. (2018), Statistical pocketbook of Maldives 2018. Retrieved from http://statisticsmaldives.gov.mv/nbs/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Statistical-Pocketbook-of-Maldives-2018-Printing.pd.

NIE. (2011), The national curriculum framework. National Institute of Education, Ministry of Education, Maldives.

Shafeeu, I. (2019), Relationship between principals’ instructional leadership and school effectiveness-Does it make a difference? Evidence from the Maldives. PhD thesis, University of Durham, UK.

Shiyama, A. (2020), Primary teacher professional learning in the Maldives: An explorative study of science process skills pedagogies. PhD thesis, The University of Bristol, UK.

The Island President, March 14 (2012): Dogwoof (accessed 12 December 2020) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ryhr_T7cRnY.

UNESCO- IBE. (2011), World Data on Education. 2010–2011. Revised, 8, 2011.

World Bank, April 10,(2013), The Maldives: A Development Success Story: April 10, 2013 (Accessed 12th December 2020) https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2013/04/10/maldives-development-success-story.