Despite romosozumab being particularly effective at reducing the risk of fracture in women with severe osteoporosis, potential safety concerns following trial data suggest the drug may cause an increased risk of heart attack. However, subsequent research has produced conflicting results.

An international team, led by Bristol Medical School researchers, sought to investigate whether, having a genetic tendency towards lower circulating levels of sclerostin — a protein expressed from bone cells which inhibits bone formation— may increase the risk of heart attack. They propose that this mimics the effect of giving the drug romosozumab, which acts to stimulate bone formation and increase bone density by blocking sclerostin.

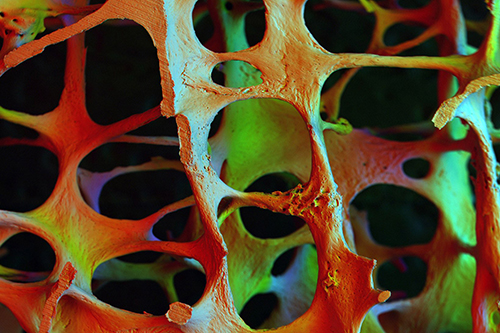

Jon Tobias, Professor of Rheumatology at Bristol Medical School: Translational Health Sciences at the University of Bristol, and one of the study's lead authors, explained: "Osteoporosis commonly affects older people, particularly women, where bones become weaker and more liable to fracture. Romosozumab is a new type of drug that is highly effective at treating this condition by blocking the protein sclerostin, which is produced by bone cells and negatively impacts bone density. Administered as monthly injections, the drug helps to increase bone density and lower fracture risk.

"We wanted to predict whether romosozumab’s action in blocking sclerostin might lead to an increased risk of heart attack, by examining effects of a genetic tendency to lower levels of sclerostin, on the basis that this might reproduce some of the effects of administering the drug."

The team applied a scientific technique called Mendelian randomisation. This approach, which uses genetic variants as proxies for a particular risk factor, established whether having a genetic tendency to lower levels of sclerostin in the circulation increases a person’s risk of 15 diseases and risk factors related to atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). These included, heart attack, stroke, type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure.

Using genetic data on 33,961 European individuals, the team identified several genetic variants associated with lower levels of sclerostin. Their analyses suggested that lowering sclerostin levels might lead to a 30 per cent increased risk of heart attack, as well as an increased risk of calcification of the arteries of the heart, hypertension and type 2 diabetes, whereas no effect was seen on stroke risk. A genetic predisposition to lower sclerostin also led to lipid profiles that were more likely to cause atherosclerosis.

Professor Jon Tobias added: "Our findings suggest that individuals genetically predisposed to lower circulating levels of sclerostin have an increased risk of cardiovascular events, reinforcing the need for strategies to minimise any potential impact of treatment with sclerostin inhibitors on heart attack risk, some of which are already in place, such as avoidance in patients with previous cardiovascular problems."

The research was supported by the University of Bristol's Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) and MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU).

Paper

'Lowering of circulating sclerostin may increase risk of atherosclerosis and its risk factors: evidence from a genome-wide association meta-analysis followed by Mendelian randomization' by Jie Zheng et al. in Arthritis and Rheumatology